by Philip Graham

I had never before wandered through Tower Records in downtown Chicago, yet it felt familiar. Why not? Every store in the corporate chain was a similar gleaming cathedral of CD and vinyl excess, multistoried with escalators and elevators, and brimfuls of such a wide selection that, once you entered, you’d find it near impossible not to discover something to love. The behemoth in New York on 66th and Broadway had always been a favorite of mine, the outlet where I’d found the music of Madredeus, that great Portuguese fado-chamber ensemble; the world-electronica of Banco de Gaia’s Last Train to Lhasa; and Vanessa Daou’s masterpiece, Zipless, her slick brooding songs set to poems by Erica Jong.

But the Chicago store could have been proud of its own promising immensity.

I was hanging out with the writer and book critic John Blades—we were two fellow music lovers on a Tower Records hunt on an idle afternoon. But John also wanted to show me this particular store because it served as the setting for one of the most powerful chapters in a novel manuscript he’d recently completed and shown me. In a way, this outing was like a return to the scene of a crime.

In that chapter of John’s novel, a nasty piece of work named Jason is stewing at the likely loss of his high school friends’ ambitious weekend party plans. His mother, without consulting anyone in the family, has responded to a flier that asked wealthy North Shore families to invite at-risk teenagers from the Cabrini-Green housing project into their homes for the four-day Thanksgiving holiday. When shy, quietly observant Terrance arrives, immediately humiliated by the mansion’s bitter contrast with his own home, all he wants to do is to return to his family. Jason sees this but doesn’t care; Terrance is an “alien invader” who will keep him from his long-planned parties. Jason decides to solve this problem by inviting Terrance on an expedition to Tower Records the day after the turkey feast, when the Black Friday shopping frenzy will ensure that store security “would be overworked and spotty.”

In the nonfictional Tower Records, John and I picked our way through the bins. Back in 1998, those days before listening stations, how could you know whether the music inside an airtight jewel box was worth taking a chance on? Over the years I’d become adept at catching the requisite clues by squinting at a CD cover image smaller than a slice of bread.

But during my teen years in the 1960s, the dimensions of 12 inch LP sleeves were the equivalent of a Sistine canvas. When my nearly sixteen-year-old self haunted the racks of the local record store (the kind driven out of business when the likes of Tower Records came to town), a certain amount of deciphering time was required, especially when an LP, at three dollars a pop, was a substantial portion of one’s allowance. Was the album’s art trying to reveal the music inside, or trying to trick you, tease you into coughing up a chunk of money for something unworthy? You had to glean from an image shaped by marketing nuance what the fluid music, trapped inside and unsold, might sound like. It was, I think, my first thrilling experience of art appreciation, because you wouldn’t know until you returned home, slit the plastic wrapping carefully, slipped out the record and set it on the turntable, if you had interpreted correctly.

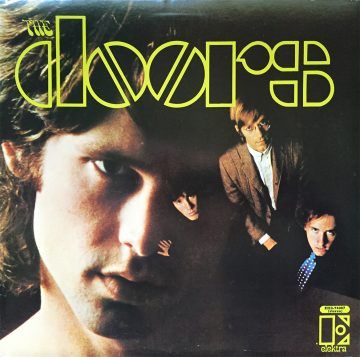

I remember in January of 1967 puzzling over the debut album of a group I’d never heard of, called The Doors. The cover was a distorted version of the Meet the Beatles cover, where squeaky-clean had morphed into unsettling, the band’s sullen faces rising from a dark background. These guys clearly had inner lives. Oddly, one of the band members was larger than the other three combined—like the distortion of a dream, but also a likely sign he was the group leader. The tough stares of the tiny others seemed to say, “Yeah, we got his back,” maybe because there was a hint of vulnerability in that probable band leader’s expression?

As young as The Doors might have been in this photo, they were far older than I, even older than the high school upperclassmen I wouldn’t mind being, those older boys privy to secrets I didn’t even know were secrets. Then I examined the back cover. The first song listed was “Break on Through (to the Other Side).” I didn’t know what that meant, but it might be worth three bucks to find out, and I paid up at the cash register. Five months later, when “Light My Fire” saturated the radio, I would indulge in the self-satisfied pleasure of having discovered a popular band long before anyone else.

*

John Blades and I continued our wandering down the Tower Records aisles. I searched through the World Music selections, one of my favorite categories, but I had trouble concentrating, because I couldn’t shake the creeping influence of my friend’s fictional Jason, who added an unsettling menace to a place I loved. Jason has come to Tower Records prepared. He employs a sharp little knife that easily opens CD jewel boxes, and he deftly palms the loosened CD into a deep jacket pocket lined with tin foil, in order to checkmate electronic sensors. After nabbing a Beck CD, he works his way from one section to another. A flabbergasted Terrance follows–he can’t believe how this rich White kid can so brazenly, efficiently shoplift his way through the store. Jason even plans ahead and steals a portable CD player from a wall rack, so that on the way back home on the El he will be able to listen to his ill-gotten gains.

Thank heavens that little monster hadn’t wandered to the World Music section and stolen a CD by Trio Patrekatt. Otherwise, I might never have discovered the wonders of the nyckelharpa.

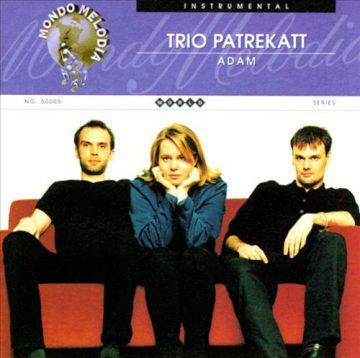

My initial attraction to the Trio Patrekatt CD was its absence of readable clues. Three young people—a woman flanked by two men—sat together on a nondescript red couch, the white wall behind them blank as an empty canvas. No indication of what music they played, or on what instruments. These multiple mysteries were just enough for me to flip the CD to read the promotional copy on the back. “Traditional Swedish music” nearly stopped me—I had little interest in that. But the group was described as a trio of cello and “two nyckelharpas (keyed fiddles).” What was a keyed fiddle? I decided to keep reading: “For the Swedish folk purist, the ethereal sound is progressive, to the musical enthusiast it is simply sublime.”

I confess the word “ethereal,” when used to describe music, will often perk me up. But “sublime”? Sublime is true liner note catnip. Purchase assured.

Back home, I discovered that the CD booklet inside almost tauntingly refused to display any image of a nyckelharpa. I had to imagine what created the beauty bursting from the speakers. Something that might be like a violin, but enhanced, fuller, and hard to describe, and when the two nyckelharpas soared in harmony, while the cello chugged along below them, the doubling of their strings inhabited a strange resonating blend of violin, organ and accordion. Ethereal, yes; sublime, indeed; but the trio’s music could swing too, transforming even a traditional polka into something far jazzier.

After several listens, I remembered that the Internet existed and surely would be happy to display an image or two of this mysterious instrument. Then came the shock of my first view of something that looked as if it had burst from the forehead of Picasso: a peculiar tiered keyboard, like some demented miniature piano, was attached to the side of a 16-stringed violin (later I learned that three of these strings are sympathetic, which resonate without being touched, as similar strings do in a sitar). I stared and stared, wondering, How in the world could anyone possibly play a nyckleharpa?

After several listens, I remembered that the Internet existed and surely would be happy to display an image or two of this mysterious instrument. Then came the shock of my first view of something that looked as if it had burst from the forehead of Picasso: a peculiar tiered keyboard, like some demented miniature piano, was attached to the side of a 16-stringed violin (later I learned that three of these strings are sympathetic, which resonate without being touched, as similar strings do in a sitar). I stared and stared, wondering, How in the world could anyone possibly play a nyckleharpa?

Certainly musicians had mastered the intricacies of nyckelharpas for centuries, going back to at least 1350 in Sweden, long enough for a wide range of performance traditions to form and repertoire to be composed for tenor-nyckelharpas, chromatic-nyckelharpas, soprano-nyckelharpas and octave-nyckelharpas. A whole vast world of music that I’d never heard to. How could I not be hooked?

I would love to offer you an example of the music of Trio Patrekatt, but unfortunately the group only briefly, brilliantly flared for Adam, their one CD. There are no videos out there that I can find to share. But the CD actually has a nook on Amazon (because what in the world doesn’t?).

Have no fear, there are many other still-thriving nyckelharpa groups out there, and one of them, Väsen, is considered the gold standard. Väsen is also a trio, one that combines nyckelharpa with guitar and viola.

Another popular group is Bazar Blå, yet another kind of trio, comprised of nyckelharpa, guitar and percussion. The nyckelharpist in the band is Johan Heden, one of the founding members of Trio Patrekatt.

I might mention that these two groups have been around for quite some time—over twenty years for Bazar Blå, and over thirty for Väsen. I suspect the reason is that, if you’re a musician, whether a drummer or a guitarist or a violist, once you find a nyckelharpa player who is willing to perform with you, then you behave yourself so you can stay in that band.

As will often happen, a single slice of a sweet new (to me) music genre will drive my hunger for the entire pie. Trio Patrekatt proved to be my gateway sugar high to the wider range of contemporary Scandinavian folk music, including Norwegian hardanger fiddle player Annbjorg Lien, Finnish accordion master Maria Kalaniemi, and Arja Kastinen’s extended improvisations on the 15-string Kantele harp. Then there’s the folk punk band Hedningarna, which sounds both new and very, very old.

Instructional Coda, Part One

I still haven’t answered the question (that I myself posed—who else was asking?): How do you play a nyckelharpa? Do you really want to know? The dilemma of this last question reminds me of a long-ago family vacation in the Dells of Wisconsin, a Midwestern vacationland with scores of water slides, three-, four-, five-storied water slides: the Tower Records of water slides! When you’ve tired of hurtling down tubes of summer-warmed water, or eating bad food (like the kabobs known locally as “steak on a stick”), then it would be time to catch a show at the Rick Wilcox Magic Theater.

So, sit back and relax. Enjoy. It’s magic.

Where’d she go, how did she get back? Can ordinary human beings shrink or expand like Alice in Wonderland? Probably not. So, how’d they do that? Such a satisfying, frustrating question. We’ll never really know, will we, no matter how many of our guesses circle the wagon.

Unless, at the end of the show, the magician were to willingly reveal one of his elaborate trick’s hidden design. Which is what Rick Wilson indeed offered to us all, a look under the hood. I remember thinking, “Yes, yes, yes, I want to know how you did that,” while at the same time, with equal force, I felt, “No, no, no, I don’t want the illusion to be ruined!” Wouldn’t Rick’s reveal somehow diminish the other magic tricks?

So, let’s be honest, aside from those ambitious souls who, after listening to these nyckelharpa samples, now want to learn how to play the instrument (or are simply interested in how all those moving parts mesh together), most readers might wish to retain the mystery of how sound is put together by the sui generis magnificence of an instrument that’s part violin, sitar and piano.

There are many explanatory videos out there, but I’ve chosen this one, by Scottish musician Griselda Sanderson, for its clarity and charm. She’s simply standing in some music festival’s quiet corner, maybe filling in the pause between sets. Plus, she gets points for mentioning that she plays not only traditional Swedish folk music with her nyckelharpa, she also records on the instrument with Juldeh Camara, a Senegalese singer, and an ngoni guitarist from Morocco, Simo Lagnawi.

So, spoiler or enhancer? Your choice.

Instructional Coda, Part Two

You may have thought we were done with Jason, but that little bastard conjured up by the writer John Blades has much more to teach us, and not only because his larcenous techniques could serve as an analogue omen of the Napster firestorm that would eventually raze Tower Records down to its bankrupted roots. Jason’s petty crimes rest on a far more disturbing, pervasive and deeper foundation.

After Jason manages to sneak out of the store without alerting any guards or alarms, Terrance catches up with him:

“You coulda got us both arrested back there.”

“Not both of us, Terrence. Only you,” Jason says. “It was you who boosted those CDs. You’re the perp, I’m just a victim. You forced me to go along for the ride. We get caught, it’ll be your black ass that’s going to jail. Won’t be mine.”

Jason has known all along that, with Terrance in tow, his own White skin is a Get Out of Jail card. That’s the deal with peeling away the layers, the risk and revelation of exposing the hidden structure of who-knows-what. Everything has a technique, and behind that something hidden awaits. You may be faced with the wonder of the unknown slipping into unsuspected beauty and musical grace. But sometimes, when following the techniques of what seems to be petty crime, a much, much larger crime is revealed.