by Michael Liss

We are not dead yet. Battered a little, yes. Frustrated, anxious, wondering about our jobs, our neighborhoods, our schools, absolutely. Definitely not dead.

We are not dead yet. Battered a little, yes. Frustrated, anxious, wondering about our jobs, our neighborhoods, our schools, absolutely. Definitely not dead.

It doesn’t mean we aren’t wounded. Last week, an open letter from the Partnership for New York City called on Mayor Bill de Blasio, in very diplomatic but clear terms, to restore essential services, clean up the City, and get it back to work. You can read the full text here, but the most interesting thing about it is the signatories, a variety of luminaries from business, real estate interests, top law firms, investment banking, etc., who, in the aggregate, probably control more assets than the combined GDP of all the countries in Western Europe.

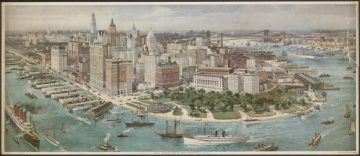

Vested interests aside, these folks are also largely right. De Blasio has become something of a punching bag because of his outsized personal ambitions as compared to his minimalist accomplishments, but the truth is, even without COVID, the Mayor’s job is an incredibly tough gig. We have an aging infrastructure, rely heavily on mass transit, are incredibly diverse ethnically and socio-economically, and have many neighborhoods where the incomprehensibly rich live cheek to jowl with the inexcusably poor. The school system alone is a stupendous challenge. In healthier times, 1.1 million kids, one in every 300 Americans, sit at a desk in a New York City classroom.

With COVID, we are back on our heels. If I were de Blasio, I’d look at my shattered outside ambitions, focus my last 16 months in office on addressing some of the City’s real needs, and find an opportunity to refurbish my image. 163 signers of the Partnership’s letter are 163 sources of cash, managerial expertise, and other resources that could be applied to our present crisis. Ask them, and they will show up—not just out of civic duty, but also because it’s good business. They might also pressure a pol or two in Washington, including some well-placed ones who currently make a sport out of hating us. Just a suggestion, Mr. Mayor.

I’d appreciate it if he would do it soon. Like everyone else, I’m tired of masks and social distancing, empty storefronts and performance halls. We crushed the curve here, but at a tremendous price, not the least of which was a loss of so many of the things that made us want to be here in the first place. Don’t believe the right-wing meme of hundreds of thousands of New York refugees lining up outside truck-rental places, with nothing more than the clothes on their backs and a Louis Vuitton suitcase. But do believe that the grace notes are critical, not just for our quality of life, but also as an engine of recovery. New York had 65 million visitors in 2019. They didn’t come for the dirty-water hotdogs.

One of my running partners (we returned to socially-distanced running about a month ago) texted me with a simple thought that summed it up: “Craving for normalcy.” It’s what I’ve been feeling for months—I need to feel even a little normal.

So, I signed up for a timed admission at the recently reopened Metropolitan Museum of Art. To me, the Met is almost an extension of Central Park, except it’s less green and there’s no running allowed. It’s a place where you can pretty much do whatever you want, if you want to do it quietly. I’ve wandered both aimlessly and with purpose, found a quiet space to read a book, even written much of a piece for 3quarksdaily.com there.

My favorite is the American Wing, and it seemed like an awfully good time to return to it. I can’t tell you that American painters are better than their European counterparts—they aren’t, but there’s something about them that appeals to my sense of place.

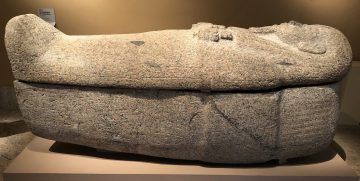

I arrived appropriately masked, passed through a variety of screens, and found myself indoors and loose. Very quickly, I realized there was an unanticipated hitch to my idea.  To get to the American Wing from the main entrance hall, you have to go through the Egyptians. A whole lot of dead people here: mummies, sarcophagi, creepy-looking linen for wrapping the deceased, amphorae for keeping their…well, you know what they keep. The mind runs amok—not to the more recent Brendan Fraser Mummy movies, which at least had a sense of humor, but the old, grainy Boris Karloff 1932 version, which emphatically didn’t.

To get to the American Wing from the main entrance hall, you have to go through the Egyptians. A whole lot of dead people here: mummies, sarcophagi, creepy-looking linen for wrapping the deceased, amphorae for keeping their…well, you know what they keep. The mind runs amok—not to the more recent Brendan Fraser Mummy movies, which at least had a sense of humor, but the old, grainy Boris Karloff 1932 version, which emphatically didn’t.

Fortunately, I have the discipline to remind myself that hope is on the way. I pick my way past the ancient weirdness (with appropriate respect—there’s absolutely no reason to tempt whatever fate hangs around these dimly lit galleries) edge into the sun-filled Sackler Wing, where definitely dead and therefore harmless crocodiles await me, past the Temple of Dendur, and then into the brave new world of the Brave New World.

The Eberhardt Court is a great space to hang out with a book (or a notebook), but I came to see things, and I turn into the first open door. I’m in a part of the Met’s formidable collection of period furniture. Highboys, clocks, end-tables, chairs, whole sitting rooms and drawing rooms, William and Mary, Queen Ann, Chippendale, Federal, Empire, pineapples and eagles, ball and claw and slipper feet and split pediments. I’m trying to decide whether this is what I want to spend time on when a voice behind me settles it by saying to her companion, “Can we get out of the Raymour and Flanigan section?”

She’s right. I want to see people doing things, not what they sat on or put their clothes in. And I’m not really looking for the posed, formal pictures of greats like Hamilton and Andrew Jackson. What I want are my old friends, paintings that, for whatever reason, draw me to them.

I love this guy: This is Boston lawyer Richard Dana by John Singleton Copley. Look at that face! Look at the hand spread across his chest! Copley was a genius at portraiture, great with detail, but here, I think he outdid himself. Who could be more distinguished (and know it) than Richard Dana?

I love this guy: This is Boston lawyer Richard Dana by John Singleton Copley. Look at that face! Look at the hand spread across his chest! Copley was a genius at portraiture, great with detail, but here, I think he outdid himself. Who could be more distinguished (and know it) than Richard Dana?

Sadly, Dana died just two years after Copley caught him like this, but there are plenty more.

Check out this active, vigorous portrait of George Washington by John Trumbull…and yes, that is a slave (William Lee) to Washington’s right. Father of our country, slave-owner, and later manumitter. Lee was freed on Washington’s death and granted a pension from Washington’s estate.

Check out this active, vigorous portrait of George Washington by John Trumbull…and yes, that is a slave (William Lee) to Washington’s right. Father of our country, slave-owner, and later manumitter. Lee was freed on Washington’s death and granted a pension from Washington’s estate.

Something a little less formal, and a little more dramatic? Like sharks? Look at “Watson and the Shark,” showing the young Brook Watson, the future Lord Mayor of London, as a shark takes his leg in Havana Harbor.

And this one, Winslow Homer’s superb “The Gulf Stream,” with a stranded, starving boatman in a dismasted fishing boat, menaced by a shark and a waterspout.

Here is Homer on a lighter note, the terrific “Snap the Whip,” showing boys playing after they’ve been released from school.

Here is Homer on a lighter note, the terrific “Snap the Whip,” showing boys playing after they’ve been released from school.

If you’ve stayed with me this long you have almost certainly figured out I’m not exactly an art scholar, but I’m going to leave you with two more favorites, both by Thomas Eakins, each quite different.

First, the extraordinarily pensive, almost entirely black and white, “The Thinker: Portrait of Louis M. Kenton.” Interesting the subject would allow himself to be portrayed this way…he is remote to the point of aloofness.

First, the extraordinarily pensive, almost entirely black and white, “The Thinker: Portrait of Louis M. Kenton.” Interesting the subject would allow himself to be portrayed this way…he is remote to the point of aloofness.

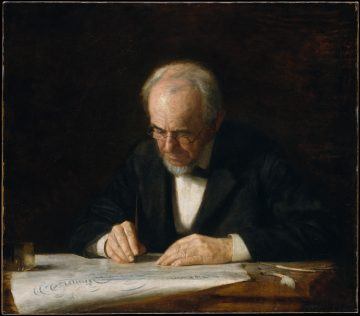

Second, Eakins’ affectionate “The Writing Master,” a portrait of his father Benjamin, who was a calligrapher. “The Writing Master” always keeps me. You can get lost in Benjamin’s old but supple hands, his skill, and his powers of concentration. I did, and then realized I had been at the Met for 90 minutes, the time I’d allotted myself to breathe other people’s air. It was time to go. I made my way back (quietly) through the undead, sliding past the statue of “Antigone Pouring a Libation over the Corpse of Her Brother Polynices,” doing my best to stifle any potential buzz-kill.

Second, Eakins’ affectionate “The Writing Master,” a portrait of his father Benjamin, who was a calligrapher. “The Writing Master” always keeps me. You can get lost in Benjamin’s old but supple hands, his skill, and his powers of concentration. I did, and then realized I had been at the Met for 90 minutes, the time I’d allotted myself to breathe other people’s air. It was time to go. I made my way back (quietly) through the undead, sliding past the statue of “Antigone Pouring a Libation over the Corpse of Her Brother Polynices,” doing my best to stifle any potential buzz-kill.

It’s a beautiful, sunny afternoon, and I walk south through Central Park in the general direction of home. There are small children chasing pigeons, people enjoying a discretely distanced picnic, dogs, bikes, runners, a jazz quartet and a minstrel, and a bride and groom. There’s a new statue on the Mall, depicting Sojourner Truth, Susan B. Anthony, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and an elderly woman who plants herself in front of it, waving her arms around, while the rest of us wait for a moment to take a picture. Then down to Poet’s Corner, where I quickly commune with William Shakespeare, who gently reminds me to start my column.

He’s right. I have to get to it, so I walk out of the Park, absent-mindedly taking a street I usually don’t use. I stop for a moment to answer a text, then realize I’m standing in front of an all-boys private school.Plastered to the front door is this gentle reminder to the lads:

Nope, we aren’t dead yet. All that restlessness, that intellectual and artistic creativity, that pushy drive for more, is not just going to evaporate, never to return. Not when the people who have that drive still want to be here, and the parents of the boys with good chins and well-cut blazers return from their summer places.

The skeptics and the doubters are wrong. They will always be wrong. We will be back.