by Robyn Repko Waller

Recent news heralds the advancement of the “first living robots,” the scientifically exciting xenobots, and their astonishing ability to self replicate.

Xenobots are millimeter-sized life forms comprised of complexes of frog stem cells (from the species Xenopus laevis), whose shape is tailor engineered by AI according to their human-prescribed task. Capable of locomotion and transport, thanks to their rigid structure and contracting, xenobots have the potential to aid in localized medicine delivery and vital maintenance and clearing functions within a living system. Xenobots may even help gather and clear microplastics. All this from a biodegradable lifeforms, capable of sustaining itself without supplementary nutrients for weeks.

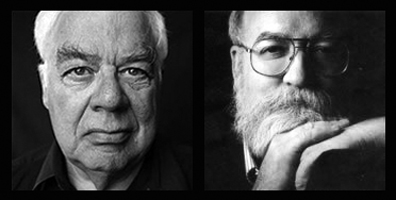

And now researchers Joshua Bongard and Michael Levin and a team of scientists at University of Vermont, Tufts, and Harvard have demonstrated that xenobots can self-replicate, or reproduce, with “parent” xenobots constructing “offspring” xenobots who then in turn produce third-generation offspring xenobots, etc. Evolutionary success? The key being their characteristic “Pac-man” form — a form determined by an evolutionary algorithm from billions of configurations to be optimally conducive to self-replication.

That xenobots are a medical and environmental breakthrough is obvious and scientifically exhilarating. Here I will set aside their groundbreaking applications and technological potential to ask a more philosophically motivated question. Read more »

Sometimes our American ideas about social problems and how to fix them are downright medieval, ineffective, and harmful. And even when our methods are ineffective and harmful, we are likely to stick to them if there is some moralistic taint to the issue. We are the children of Puritans, those refugees who came to America in the 17th century to escape King Charles.

Sometimes our American ideas about social problems and how to fix them are downright medieval, ineffective, and harmful. And even when our methods are ineffective and harmful, we are likely to stick to them if there is some moralistic taint to the issue. We are the children of Puritans, those refugees who came to America in the 17th century to escape King Charles.

One of my earliest memories was of Christmas Eve in 1954. I was about 3 or 4 years old, playing under a table at my grandmother’s house. My sister and a cousin were with me, playing with a small wooden crate filled with straw. The crate represents the manger in the stable in Bethlehem 1,954 years ago, where the animals welcomed the baby Jesus, since there were no rooms in the inn. We three kids were waiting for the adults to come to the table to join us for Wigilia, the traditional Christmas Eve feast, after which we would move to the living room, sing Polish Christmas Carols, and wait for an uncle disguised as Santa to arrive with presents for everyone.

One of my earliest memories was of Christmas Eve in 1954. I was about 3 or 4 years old, playing under a table at my grandmother’s house. My sister and a cousin were with me, playing with a small wooden crate filled with straw. The crate represents the manger in the stable in Bethlehem 1,954 years ago, where the animals welcomed the baby Jesus, since there were no rooms in the inn. We three kids were waiting for the adults to come to the table to join us for Wigilia, the traditional Christmas Eve feast, after which we would move to the living room, sing Polish Christmas Carols, and wait for an uncle disguised as Santa to arrive with presents for everyone. Over the years I have heard many stories about Mahalanobis. One relates to his youth. He and Sukumar Ray (Satyajit Ray’s father, a pioneer in Bengali literature of nonsense rhymes and gibberish) were the two contemporary Brahmo whiz kids active in literati circles. They used to arrange regular meetings at someone’s home for serious discussion. But as usually happens in such Bengali middle-class gatherings, much time was taken up in the serving and enjoyment of food delicacies. Mahalanobis objected to this and said this was leaving too little time for discussion. So he sternly announced that from now on no food should be served in the meeting. For the next couple of times people morosely accepted the rule. But Sukumar subverted it, by one time arriving a little early and persuading the food-preparers in the household (usually women) that for the sake of the morale in the meeting, food-serving should be resumed. By the time Mahalanobis arrived, everybody was relishing the delicacies, which infuriated him, but he gave up.

Over the years I have heard many stories about Mahalanobis. One relates to his youth. He and Sukumar Ray (Satyajit Ray’s father, a pioneer in Bengali literature of nonsense rhymes and gibberish) were the two contemporary Brahmo whiz kids active in literati circles. They used to arrange regular meetings at someone’s home for serious discussion. But as usually happens in such Bengali middle-class gatherings, much time was taken up in the serving and enjoyment of food delicacies. Mahalanobis objected to this and said this was leaving too little time for discussion. So he sternly announced that from now on no food should be served in the meeting. For the next couple of times people morosely accepted the rule. But Sukumar subverted it, by one time arriving a little early and persuading the food-preparers in the household (usually women) that for the sake of the morale in the meeting, food-serving should be resumed. By the time Mahalanobis arrived, everybody was relishing the delicacies, which infuriated him, but he gave up.

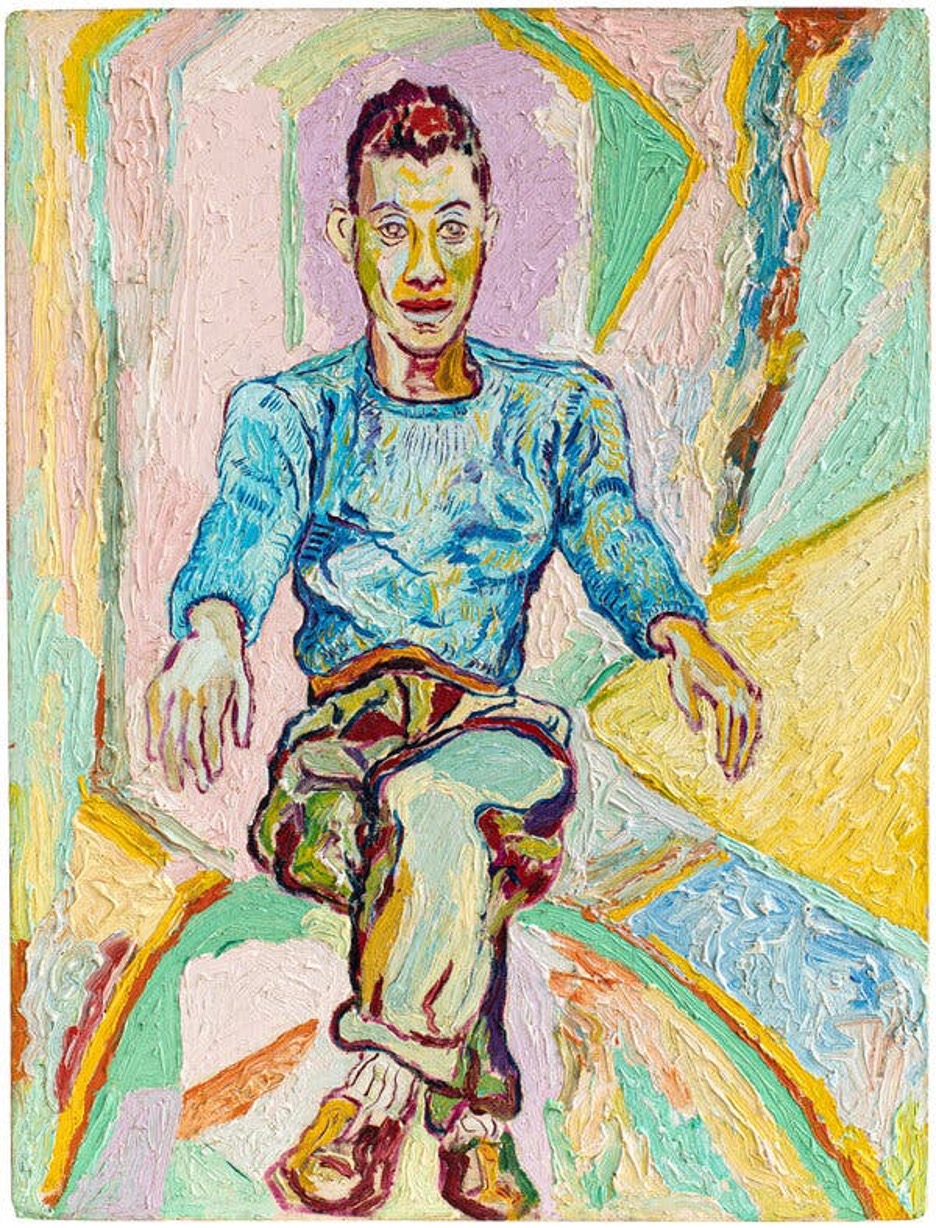

Beauford Delaney. James Baldwin (Circa 1945-50).

Beauford Delaney. James Baldwin (Circa 1945-50). A couple of weeks ago, on the pages of this website,

A couple of weeks ago, on the pages of this website,

One of those mysterious concepts that we use as a criterion for judging a novel or film is a “sense of place.” I call it mysterious because it’s so often poorly defined—we recognize it because we can feel it, but what goes into creating it? How can one go about transporting a reader, for example, into a time and place via text? I’m under the impression that if asked this question, most people would mention things like using the five senses to describe a character’s impressions of his or her surroundings, or providing detail via adjectives and adverbs. This may be a gross generalization, but it’s what I’ve gathered from my experience in creative writing courses. It’s also the sense I get from reading short stories in literary journals, which seem to be where aspiring writers publish their attempts at fiction. I often find this writing technically good, but lifeless; it has all the components of effective writing but doesn’t add up to anything compelling. I don’t mean to suggest that I could do better, but I do know what I enjoy reading and what I don’t.

One of those mysterious concepts that we use as a criterion for judging a novel or film is a “sense of place.” I call it mysterious because it’s so often poorly defined—we recognize it because we can feel it, but what goes into creating it? How can one go about transporting a reader, for example, into a time and place via text? I’m under the impression that if asked this question, most people would mention things like using the five senses to describe a character’s impressions of his or her surroundings, or providing detail via adjectives and adverbs. This may be a gross generalization, but it’s what I’ve gathered from my experience in creative writing courses. It’s also the sense I get from reading short stories in literary journals, which seem to be where aspiring writers publish their attempts at fiction. I often find this writing technically good, but lifeless; it has all the components of effective writing but doesn’t add up to anything compelling. I don’t mean to suggest that I could do better, but I do know what I enjoy reading and what I don’t.