by Eric J. Weiner

January, 2022. East End, Long Island, NY. It’s getting colder. I just recovered from a bout with COVID. I am sitting around the fire pit sipping tequila, drinking homemade bone broth from a mug, and watching lists of very important dead people, ripped from various newspapers and magazines, burn in the fire. Life is good.

January, 2022. East End, Long Island, NY. It’s getting colder. I just recovered from a bout with COVID. I am sitting around the fire pit sipping tequila, drinking homemade bone broth from a mug, and watching lists of very important dead people, ripped from various newspapers and magazines, burn in the fire. Life is good.

It is curious to me that the ending of each calendar year should signal the production of these lists. Against the backdrop of so much death from COVID in 2021, they are exclusively brief and, in the Marcusian sense, one-dimensional. Commodify your nostalgia: the bad and ugly exchanged whole cloth for the good. Death as salve, all is forgiven or, at the least, quickly forgotten. Beck got it right: “Time is a piece of wax falling on a termite/Who’s choking on the splinters.” No one gets out alive. But for those of us who are teachers, the lessons we learned from our dead brothers and sisters, those intimates who have touched and transformed our lives in deep and meaningful ways, can be reanimated through our teaching.

From the pedagogical perspective, the lexicon of death is not about lore, myth-making, or some other practice of forgetting. Rather, it suggests a critical practice of recognition that is concerned with how they lived their lives; how they taught their own students; how they treated their colleagues; the way they represented their work; the way they situated themselves within and beyond the university and school; the way laughter informed their interactions; and the seriousness by which they undertook their various social/political/educational projects. Read more »

Three things we know about #BLM, two obvious, one a bit more subtle.

Three things we know about #BLM, two obvious, one a bit more subtle.

2022 is alive, a babe come hale and hollering to join its sisters 2020 and 2021, siblings bound by pandemic. Everybody stood to see off 2022’s older sister 2021, like we all did 2020 before her. Out with the old. Quickly, please.

2022 is alive, a babe come hale and hollering to join its sisters 2020 and 2021, siblings bound by pandemic. Everybody stood to see off 2022’s older sister 2021, like we all did 2020 before her. Out with the old. Quickly, please.

At my ISI office there were several good economists. Apart from TN, there was B.S. Minhas, Kirit Parikh, Suresh Tendulkar, Sanjit Bose (my friend from MIT days), V.K. Chetty, Dipankar Dasgupta, and others. Of these in many ways the most colorful character was Minhas. A shaved un-turbaned Sikh, he used to tell us about his growing up in a poor farmer family in a Punjab village, where he was the first in his family to go to school. He went to Stanford for doctorate, before returning to India. He relished, a bit too much, his role as the man who spoke the blunt truth to everyone including politicians, policy-makers and academics. He illustrated his Punjabi style by telling the Bengalis that he had heard that in Bengal when a man had a tiff with his wife, he’d go without food rather than eat the food his wife had cooked; he said at home he did quite the opposite: “I go to the fridge, take out my food and eat it; then if I am still upset, I go to the fridge again and take out my wife’s food and eat it all up—serves her right!”

At my ISI office there were several good economists. Apart from TN, there was B.S. Minhas, Kirit Parikh, Suresh Tendulkar, Sanjit Bose (my friend from MIT days), V.K. Chetty, Dipankar Dasgupta, and others. Of these in many ways the most colorful character was Minhas. A shaved un-turbaned Sikh, he used to tell us about his growing up in a poor farmer family in a Punjab village, where he was the first in his family to go to school. He went to Stanford for doctorate, before returning to India. He relished, a bit too much, his role as the man who spoke the blunt truth to everyone including politicians, policy-makers and academics. He illustrated his Punjabi style by telling the Bengalis that he had heard that in Bengal when a man had a tiff with his wife, he’d go without food rather than eat the food his wife had cooked; he said at home he did quite the opposite: “I go to the fridge, take out my food and eat it; then if I am still upset, I go to the fridge again and take out my wife’s food and eat it all up—serves her right!”

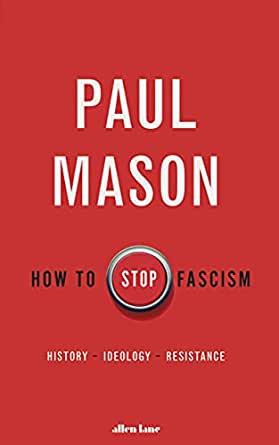

In today’s political world where liberal democracy is purported to have triumphed and ‘the end of history’ is supposed to be with us, many people might be content to rest on their laurels that fascism has been confined to the dustbin of political history, and at most its supporters on the fringe of contemporary politics. Not so however, for Paul Mason. For him ‘fascism is back’ and poses a real threat to democracies. Indeed, so convinced is he of his argument that fascism is emerging as a force to be reckoned with, his recent book How to Stop Fascism: History, Ideology, Resistance is a call to arms for greater understanding of its modern manifestations, and to resist its influence in politics.

In today’s political world where liberal democracy is purported to have triumphed and ‘the end of history’ is supposed to be with us, many people might be content to rest on their laurels that fascism has been confined to the dustbin of political history, and at most its supporters on the fringe of contemporary politics. Not so however, for Paul Mason. For him ‘fascism is back’ and poses a real threat to democracies. Indeed, so convinced is he of his argument that fascism is emerging as a force to be reckoned with, his recent book How to Stop Fascism: History, Ideology, Resistance is a call to arms for greater understanding of its modern manifestations, and to resist its influence in politics. In

In

Dorothea Tanning. Notes for An Apocalypse, 1978.

Dorothea Tanning. Notes for An Apocalypse, 1978.

Covid has given rise to a variety of counterintuitive mathematical outcomes. A good example is this recent headline (link below): One third of those hospitalized in Massachusetts are vaccinated. Anti-vaxxers have seized on this and similar such factually accurate headlines to bolster their positions. They, and others as well, interpret them as evidence that the vaccine isn’t that effective or perhaps hardly works at all since even states with very high vaccination rates seem to have many breakthrough infections that lead to hospitalization. Contrary to intuition, however, such truthful headlines actually indicate that the vaccine is very effective. I could cite common cognitive biases, Bayes’ theorem, graphs, tables, and formulas to explain this, but a metaphor involving fruit may be more convincing and more palatable.

Covid has given rise to a variety of counterintuitive mathematical outcomes. A good example is this recent headline (link below): One third of those hospitalized in Massachusetts are vaccinated. Anti-vaxxers have seized on this and similar such factually accurate headlines to bolster their positions. They, and others as well, interpret them as evidence that the vaccine isn’t that effective or perhaps hardly works at all since even states with very high vaccination rates seem to have many breakthrough infections that lead to hospitalization. Contrary to intuition, however, such truthful headlines actually indicate that the vaccine is very effective. I could cite common cognitive biases, Bayes’ theorem, graphs, tables, and formulas to explain this, but a metaphor involving fruit may be more convincing and more palatable.