by Brooks Riley

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Herbert Harris

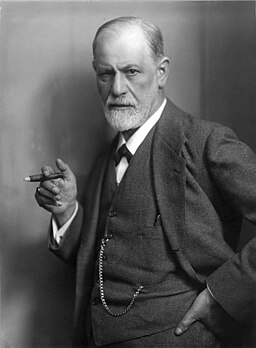

I began my psychiatric training in 1990, the year that marked the start of a program called the “Decade of the Brain.” This was a well-funded, high-profile initiative to promote neuroscience research, and it succeeded spectacularly. New imaging techniques, molecular insights, and psychopharmacological discoveries transformed psychiatry into a vibrant biomedical science. The program brought thousands of careers, including my own, into the neurosciences.

Despite its progress, the Decade of the Brain also widened an existing rift. This was the large gap between the psychoanalytic tradition and the biological sciences. The divide wasn’t new. Freud started with neurology but shifted to psychoanalysis when the brain sciences of his time couldn’t fully explain the complexities of the mind. For the first half of the 20th century, psychoanalysis was the main way to understand mental illness. Then, in the 1950s, new psychiatric drugs appeared: chlorpromazine for psychosis, lithium for mood disorders, and antidepressants for depression. For the first time, it seemed possible to treat mental illness by directly targeting the brain, rather than long-term therapy or institutional care.

By the time I was a resident, these diverging traditions had opened into a chasm. On one side was biological psychiatry, focused on neurotransmitters, neuroimaging, and cognitive-behavioral treatments, with outcomes that could be measured and tested. On the other side were psychoanalysis and its branches: attachment theory, object relations, and the investigation of unconscious conflicts through language, narrative, and symbolism. They had become separate languages, spoken within distinct professional communities, each wary of the other. There were occasional efforts at rapprochement, but little sustainable progress. By the end of the Decade of the Brain, reconciliation seemed almost impossible. I was fortunate to be in a training program that had a research track, allowing me to work in a lab, but I also had mentors who were distinguished analysts. It was like being in two different residencies.

Both have proven valuable over the years, but I never expected them to converge. However, today, circumstances appear to be shifting. A merging of neurobiology, computational neuroscience, and neuroimaging has created a new paradigm: active inference. For the first time, we can start to identify strong links between analytic models of the mind and biological models of the brain. Read more »

by David Winner

The election of a black president in 2008 invoked a groundswell of rage among white American racists that led to Donald Trump’s first victory in 2016.

The rage was so intense, the MAGA storyline so compelling, that many white folks (along with increasing numbers of non-white folks) believed Trump’s false story that the election was stolen. Then January 6, and January 6 denialism joined Biden’s stolen election among the many false stories being told across the nation.

More and more of them started to circulate as the 2024 election approached. The Haitian community in Springfield, Ohio was accused of barbecuing cats by J.D. Vance, Donald Trump and others. A blurry video from something called Red States News depicted black people (not necessarily Haitian), barbecuing, and cats with zero inference or evidence of any connection between these things.

Which brings me back to what seems like a more innocent time and a more innocent racist urban folk legend, variations of which appeared to be moving up the eastern seaboard during the early days of covid.

Spring 2020

I’m in Virginia in an Air B&B near my elderly father’s house waiting to test negative for covid in order to move in with him. After the test, I walk over to the house in which I grew up and ring the bell. I’ll talk to him from outside. My eyes tear. This is the longest I’ve gone without seeing him since my mother got really sick from Parkinson’s over a decade before.

He wants me to come inside, but I tell him that I can’t. But he is upset. He has hurt his foot and wants me to look at it. He just wants care, and I don’t have it in me to refuse him. Holding my breath to avoid breathing on him through my mask, I inspect his foot. We sit on the front porch, a locus of pre-dinner cocktails in the seventies and eighties that has fallen into disuse. Read more »

Uuriintuya Dagvasambuu (Mongolia). Woman in Ulaanbaatar: Dreams Carried by Wind, 2025.

Uuriintuya Dagvasambuu (Mongolia). Woman in Ulaanbaatar: Dreams Carried by Wind, 2025.

Acrylic on canvas.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Michael Liss

In 16th century Prague, so the legend goes, the sage Rabbi Judah Loew, Talmudist, philosopher, mystic, mathematician, and astronomer, searching desperately for a way to protect his community from violence, took a figure made of soil or clay, and, through sacred words, animated him. The product of his efforts, a Golem, served as an unflagging, inexhaustible bodyguard until, soulless and untethered as he was, he grew so powerful that he menaced the people he was charged to protect, and the Rabbi was forced to de-animate him.

The ancient Greeks had a similar myth, of Talos, a living statue made of bronze, either the last of a race of bronze men, or newly forged by the divine smith Hephaestus. When Zeus delivered Europa to Crete, he gave her Talos as a sentinel and defender. Three times a day, Talos would circle the island, throwing rocks at pirates or other intruders. Talos too perished when enchanted by the sorceress Madea, who tricked him into loosening a bolt on his ankle, thereby giving up his life’s blood.

In more modern times, the story of life from inanimate material is echoed in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, where her Creature has great strength, but suffers grievous emotional pain when in contact with humans and ultimately kills his creator’s family. It’s altogether possible that the next Creature, Talos, or Golem will be AI, as we humans are not good at satisfying our curiosity, nor in moderating our urge to control and dominate. For these (guilty) pleasures we often risk far more than we thought we would, and are left with the collateral damage.

So it is with the Trump Golem. He was animated for a purpose (a discontent with the status quo is a gross oversimplification, but will do) and is currently rampaging in a way that many did not anticipate. Trump I was gaudy and messy, but until January 6th (soon to be a major motion picture with a semi-fictional Horst Wessel figure) didn’t seem to be life-altering. Trump II, well, “Cry ‘Havoc!’ and let slip the dogs of war.”

That “war” has many fronts and many tools, but, for this essay, we are going to have to talk about money. Read more »

by R. Passov

I went into a store the other day. An old man helped me pick out a pair of running shoes and, while doing so, thanked his friend for stopping by to ask how his health issue was coming along. The friend asked in such a way as to let it be known that the issue was something both fatal and not in a place that you would ever point to in public.

The old man who helped me to find the right running shoe, though infirm, had a doggedness about him. It wasn’t enough for me to say a pair fit comfortably. I had to demonstrate which meant jogging on a tired strip of astroturf set off against a far wall. I’m 67 years of age and not accustomed to running in front of an audience. And yet, I ran.

I ran in a store that had been frustrating to find. On a long street in a neighborhood that, once filled with small enterprises providing footholds to working class families dreaming of their next generation’s college graduations, looks like a stretched rubber band of mostly empty store fronts. Somewhere in that bland row of cheap, merchant glass is a hard-to-find half door under an awning shared with some other business not anywhere near retail running shoes.

You run on your toes, the old man said, as though it were the equivalent of saying that I’m not really a runner. And you pronate and the shoes you’re asking for are not the right shoes and your size is not an eleven but instead an 11.5. I ran in different pairs of shoes until he was satisfied.

As I was running, I felt a hard sadness that comes from knowing that shoe store will go the way of the old man, will be another loss in a long line and the old man knows this. He knows just as he’s dying of cancer, his brand of commerce is being strangled by Amazon. Read more »

Sun through leaves throws

shadows on his face as if

a dappled stallion,

alone in time, a tick,

a heartbeat, far out in time

elliptical and long as the

orbit of Uranus—

eighty-four of this boy’s

life-to-be in years to come

Jim Culleny

5/26/12; edited 8/30/25

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Kyle Munkittrick

There is an anti-AI meme going around claiming that “Writing is Thinking.”

Counterpoint: No, it’s not.

Before you accuse me of straw-manning, I want to be clear: “Writing is thinking” is not my phrasing. It is the headline for several articles and posts and is reinforced by those who repost it.

Paul Graham says Leslie Lamport stated it best:

“If you’re thinking without writing, you only think you’re thinking.”

This is the one of two conclusions that follow from taking the statement “Writing is thinking” as metaphysically true. The other is the opposite. Thus:

Both of these seem obviously false. It’s possible to think without writing, otherwise Socrates was incapable of thought. It’s possible to write without thinking, as we have all witnessed far too often. Some of you may think that second scenario is being demonstrated by me right now.

Or are you not able to think that until you’ve written it?

There are all sorts of other weird conclusions this leads to. For example, it means no one is thinking when listening to a debate or during a seminar discussion or listening to a podcast. Strangely, it means you’re not thinking when you’re reading. Does anyone believe that? Does Paul Graham actually think that his Conversation With Tyler episode didn’t involve the act of thinking on his part, Tyler’s, or the audience?

Don’t be absurd, you say. Of course he doesn’t think that. Read more »

by Dwight Furrow

Wine tasting is a great seducer for those with an analytic cast of mind. No other beverage has attracted such elaborate taxonomies: geographical classifications, wine variety classifications, quality classifications, aroma wheels, mouthfeel wheels, and numerical scores. To taste wine, in this dominant model, is to decode—to fix a varietal essence, to pin down terroir as if it were a stable identity, to judge typicity (i.e. its conformity to a norm) as though it were the highest aesthetic ideal. The rhetoric of mastery in wine culture depends on this illusion of stability: Cabernet must show cassis and graphite, Riesling must taste of petrol and lime, terroir speaks in a singular tongue waiting to be translated.

Wine tasting is a great seducer for those with an analytic cast of mind. No other beverage has attracted such elaborate taxonomies: geographical classifications, wine variety classifications, quality classifications, aroma wheels, mouthfeel wheels, and numerical scores. To taste wine, in this dominant model, is to decode—to fix a varietal essence, to pin down terroir as if it were a stable identity, to judge typicity (i.e. its conformity to a norm) as though it were the highest aesthetic ideal. The rhetoric of mastery in wine culture depends on this illusion of stability: Cabernet must show cassis and graphite, Riesling must taste of petrol and lime, terroir speaks in a singular tongue waiting to be translated.

But I think this way of representing wine is misleading. Wine is not a stable object to be deciphered but a field of shifting relations into which the taster steps (like Heraclitus’s river.) What if its aesthetic force lies not in measuring a wine against its ideal type but in staging tensions, oscillations, and fleeting harmonies that refuse to hold still?

The claim I will develop is that wine is not a fixed bundle of flavors but a dynamic system, always in motion, whose meaning arises through modulation—the way its elements shift and inflect one another; through differential relations—the contrasts that give each element its character; and through synthetic experience—the way these relations come together as a whole unfolding across time. To taste wine well is not to solve a puzzle, but to follow its movement as it reveals itself. Read more »

by Nils Peterson

I thought to myself that one day I’ll have to write an essay entitled “Goodbye Dorothy Parker, Apologies Edgar Guest.” It would have as its epigraph a quotation from Flaubert in a letter to Louise Colet, “But wit is of little use in the arts. To inhibit enthusiasm and to discredit genius, that is about all. What a paltry occupation, being a critic…. Music, music, music is what we want! Turning to the rhythm, swaying to the syntax, descending further into the cellars of the heart.” Yes, “swaying to the syntax,” poetry and music swaying in a dance – lovers really. This morning I thought this might be the day.

Poetry used to be popular. People read it all the time. Many newspapers had a daily poem. My mother wrote poems in both Swedish and English that appeared in a Swedish-American newspaper. Edgar Guest’s 1916 collection “A Heap o’ Livin” sold more than a million copies. But then in 1922 came the catastrophe of “The Wasteland,” and “real” poetry became the possession of the elite. Consequently, it gradually disappeared from newspapers and other general publications.

The title of Guest’s book came from a line in the title poem – “it takes a heap o’ livin’/ To make a house a home.” Some wit wrote “It takes a heap o’ heaping to make a heap a heap.” Well yes, funny. Dorothy Parker wrote “I’d rather flunk my Wasserman test/Than read a poem by Edgar Guest.” Witty, yes. Funny, no. Think how that attitude wants to separate those of us who love “The Wasteland” from the rest of the world who love a different kind of poetry.

A friend told me this story about his father: “My dad [at] a discussion in the big room at the Minnesota Men’s Conference.… (Once my brother and I coaxed our dad to come up for three days….) Robert Bly was asked about the meaning of a line in one of his poems… as he frequently was. In this instance… My dad leaned forward to listen… And Robert said ‘I have no idea what that means.’ That sealed the deal for my dad. He would much rather read Edgar Guest than some poet that doesn’t know what he means.”

Yes, sometimes it really is hard to say what a line means. Sometimes you don’t quite know yourself. Sometimes it would take too long to explain. Sometimes the place is not the right place for explanation. So, I sympathize with Robert, but I sympathize with my friend’s dad too. Read more »

by Christopher Hall

2007’s Bioshock stands as a touchstone for many on the by-now perennial, and admittedly somewhat tiresome, question of whether video games are or could be art. I remember the game for what one remembers most first-person-shooters for – the joy of slaughtering successive waves of digital monsters – but there is one moment in the game that stands out in a different way. (Spoilers ahead.)

As is typical in these sorts of games, you are given tasks, usually by a non-player character (NPC) of some sort, which you must complete in order to progress the game. The NPC – Altas – prefaces all of his requests to the player character (PC) – Jack – with the phrase “Would you kindly.” It turns out that Jack has been conditioned to do whatever he is told when a request is so phrased. In a distinctly postmodern-ish moment, the player is called upon to think of themselves in relation to the PC. They are not compelled in the same way Jack is, but absent quitting the game entirely, they have no other option but to continue. You can either do what you are assigned to do or abandon the system entirely (food for thought there). Add to this the overall setting of Bioshock: a dystopia initially created by an industrialist operating under a libertarian ideology recognisably derived from Ayn Rand. So the ultimate quest for social and economic freedom conceals instead brutal coercion. I am not silly enough to attempt a definition of aesthetic sensation, but the frisson this caused was enough to qualify in my mind.

Is Bioshock art? Could it be art? It is 20 years since Aaron Smuts asked “Are Video Games Art?” in Contemporary Aesthetics (responding to a 2000 article from Jack Kroll who firmly answered “no”), and 16 years since John Lanchester asked roughly a similar question (“Is It Art?”) in the London Review of Books. Smuts noted that there is already a tenuous distinction between art and sports:

Although we may say that a baseball pitcher has a beautiful arm or that a boxer is graceful, when judging sports like baseball, hockey, soccer, football, basketball and boxing, the competitors are not formally evaluated on aesthetic grounds. However, sports such as gymnastics, diving and ice skating are evaluated in large part by aesthetic criteria. One may manage to perform all the moves in a complicated gymnastics routine, but if it is accomplished in a feeble manner one will not get a perfect score….One might argue that such sports are so close to dance that they are plausible candidates to be called art forms.

Even if video games are essentially competitive, Smuts notes, just because that is the case does not render them “inimical” to art. If one enters a poem in a poetry contest and wins, one’s poem does not cease to be art. Read more »

by Tim Sommers

Even as we want to do the right thing, we may wonder if there is really, in some objective sense, a right thing to do. Throughout most of the twentieth-century most Anglo-American philosophers thought not. They were mostly some sort of subjectivist or other. Since they focused on language, the way that they tended to talk about it was in terms of the meaning of ethical statements. Ethical statements, unlike factual claims, are subjective expressions of our emotions or inclinations and can’t really be true or false, right or wrong, in any objective sense.

Emotivists, for example, argued that when I say something is good or bad, I am just expressing my like or dislike. This is sometimes referred to as the “Yay! Boo!” theory. Others argued that ethical statements are more like descriptions of our subjective states or imperatives commanding or exhorting others to act in the way we prefer they would.

Some philosophers took a subtler approach. J.L. Mackie’s “error-theory,” for example, accepted that people mostly believe that ethical statements can be correct or incorrect and that people do mean to do more than express themselves when making ethical claims. Unfortunately, Mackie says, there is nothing that makes it so. When I say something is bad, I may imply that there is an external standard according to which it is bad, some source of objectivity beyond my emotions or idiosyncratic beliefs, that makes this so. But all moral talk, including this style of “objective” moral talk, fails to be meaningful because nothing could make it objectively so. Hence, moral language needs to be reinterpreted in some subjectivist way.

Of course, philosophers outside the tradition of analytic philosophy have also been skeptical of the objectivity of morality. One of Nietzsche’s “terrible truths” is that most of our thinking about right and wrong is just a hangover from Christianity and it will eventually (soon!) dissipate. We are in no sense moral equals, he said. Democracy is a farce. The strong should rule the weak.

(Plus, there is no god. Life is meaningless. We have no free will. We suffer more than we experience joy. He was a real riot at parties, I bet.)

I wonder what it would be like if most people really believed that claims about what is right or wrong, good or bad, or just or unjust, were just subjective expressions of our own emotions and desires. What would our shared public discourse, and our shared public life, look like if most people believed that?

I fear that we are like the cartoon character who has gone over a cliff, but is not yet falling, only because we haven’t looked down yet. Read more »

by Priya Malhotra

Someone asked me recently how I was doing, and I said “Fine,” without thinking. Then I heard myself—how practiced, how precise. “Fine” is code. It’s short for: I’m tired, but I can’t afford to be. I’m grateful, but I’m lonely. I’m not drowning, but I’m not exactly swimming either.

The truth is, “fine” might be one of the most disingenuous words in the English language. Not because it’s a lie, necessarily, but because of everything it carefully conceals. It’s the duct tape of conversation—quick, convenient, silent about its own compromise. When we say we’re fine, what we often mean is: this isn’t the time or the place. Or: I don’t know how to say more without unraveling. Or even: I’ve said “fine” for so long that I’m not sure what’s underneath it anymore.

What’s astonishing is how socially sanctioned this word has become—how ubiquitous, how unquestioned. It has infiltrated emails, doctor’s offices, family dinners, therapy sessions, even the most intimate conversations. A partner asks how you are: “Fine.” A friend texts from a continent away: “Fine.” Your mother calls, her voice already brimming with unsaid things: “Fine.” It is at once an answer, a defense, and a diversion. We wear it like a laminated name tag: nothing to see here.

But “fine” is not a neutral word. It is a performance. And like all performances, it costs something.

Part of the power of “fine” lies in its plausible deniability. Unlike “great,” it doesn’t overpromise. Unlike “terrible,” it doesn’t beg follow-up. It hovers in the middle—a shrug in word form. Say it enough, and you can float through an entire life without anyone really looking at you too closely. Or worse, without anyone realizing that you needed them to. It is, in many ways, the perfect linguistic technology for a world uncomfortable with emotional mess.

I sometimes wonder when I first learned the word in this way. Not just its dictionary definition, but its psychological function. Perhaps it was in adolescence, when the body becomes unruly and language begins to carry risk. Or perhaps earlier, watching the adults around me deploy “fine” with such ease, such quiet choreography. The way my mother might say it after a long day, her eyes betraying the ache in her bones. The way my father might use it to end an argument without conceding ground. The way teachers, neighbors, bank tellers, and strangers on the bus all seemed to carry it like a passport—something that allowed them to move through the world without inspection.

It wasn’t just about avoiding truth. It was about avoiding exposure.

There is something uniquely contemporary about this relationship to “fine.” Read more »

Two types of lichens growing on a bridge in Munich. And a cable of some kind.

Oh, GPT5 has identified the cable: “This is a heavy-duty flexible rubber power cable, often used outdoors, on construction sites, for temporary power distribution, stage/event equipment, or industrial settings where durability is important. The 3G2.5 size would typically be used for 230V power tools, lighting rigs, or extension leads — not for tiny electronics, but for robust electrical loads.”

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Ken MacVey

There are many causes of Trump’s double ascent as president, including, perhaps just randomness, such as Comey’s re-opening of the FBI investigation of Hillary Clinton 11 days before the 2016 election supposedly based on a belatedly discovered laptop. But it can be argued there were a number of background features in our economic, legal, and political landscape that would still have made some version of Trumpism more likely with or without Donald Trump as its specific exemplar.

Here we will review how the stage was set for the establishment of America’s version of crony capitalism even if Donald Trump had been sent back by the voters to The Apprentice instead of the White House. The focus will be on two factors: the “corporate greed is good” ethos that Milton Friedman helped promote and Supreme Court decisions, such as Citizens United, that radically transformed how election campaigns are funded. The two in fact go hand in hand in fueling crony capitalism that ironically runs over the vision of capitalism Friedman promoted and the rule of law upon which the Supreme Court’s authority rests. We will then see how Trump 2.0 has taken full advantage of this stage setting.

What Is Crony Capitalism?

The phrase “crony capitalism” refers to reciprocal relationships between elite groups of monied businesses and individuals on one hand and political officials on the other within a backdrop of private and public sectors. By these relationships each side economically and politically prospers by the exchange of money and government favors on a transactional basis. This seemingly populist phrase apparently was coined in the 1980s by Time magazine’s business editor. Yet the phrase in recent years has been ascendant, used both by leftist anti-capitalists and right-wing conservatives and libertarians to disparage government and business relationships they disfavor. The specific phrase has even gained attention in some academic circles as a designated field of study. These studies focus on dealmaking between financially well to do elite businesses and key public officials by which “scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours” dealings they hope to prosper. These studies have focused on countries in East Asia and Latin America and particularly India and Russia. So far, the United States not so much.

Stanford political scientist Stephen Haber, in an essay on “The Political Economy of Crony Capitalism,” argues that these relationships flourish when the rule of law and governance institutions such as an independent legislature or judiciary are weak or lacking. He hypothesizes that because businesses cannot rely on conventions and institutions to provide a stable framework to protect property rights businesses have to resort to financial incentives to get political officials to provide an alternative form of stability. Businesses recognize dictatorial or capricious governments have the power to take away their property and thus these businesses are willing to shell out money as an insurance policy against political caprice. Read more »

by David Beer

A good weather colloquialism can be quite suggestive. Take skafrenningur, an Icelandic expression for a ‘blizzard from the ground up’. It occurs when loose snow is hurled around by gusting winds. A pixelated yet impenetrable wall of snow. You can neither properly see through one nor, without great struggle, walk far within one. As the mention of a skafrenningur in Yrsa Sigurdardóttir’s recently translated novel Can’t Run Can’t Hide illustrates, it’s a particularly good weather phenomenon for producing a sense of being trapped. Creepy mystery aside, it is a book about weather. It couldn’t function without it. In a warmer climate the victims might simply have strolled away at the first sign of danger. As Sigurdardóttir put it herself in a short essay on the key features of ‘Nordic noir’ for The TLS, ‘and snow. Don’t forget the snow.’

A good weather colloquialism can be quite suggestive. Take skafrenningur, an Icelandic expression for a ‘blizzard from the ground up’. It occurs when loose snow is hurled around by gusting winds. A pixelated yet impenetrable wall of snow. You can neither properly see through one nor, without great struggle, walk far within one. As the mention of a skafrenningur in Yrsa Sigurdardóttir’s recently translated novel Can’t Run Can’t Hide illustrates, it’s a particularly good weather phenomenon for producing a sense of being trapped. Creepy mystery aside, it is a book about weather. It couldn’t function without it. In a warmer climate the victims might simply have strolled away at the first sign of danger. As Sigurdardóttir put it herself in a short essay on the key features of ‘Nordic noir’ for The TLS, ‘and snow. Don’t forget the snow.’

Occurring mostly in a remote converted farmhouse and adjoining luxury custom-built family home, the chapters alternate between the days before and after a deeply grisly event. The past sits uncomfortably alongside the present. As well as the time switching chapters, the old stone cottage rests awkwardly beside the connected hyper-modern glass-finish of the overbearing new-build. A few of the characters might be described as semi-detached too. Then there are hints at local discomfort, with signs of change and a loss of tradition.

The house is connected to civilization only by a treacherous road, miles of snow covered land and a recently vandalized communications mast. The mast had been installed solely to serve that farm, at the wealthy owner’s personal expense. When the internet and phone links disappear permanently the Wi-Fi box is hurriedly turned off and on, repeatedly. A futile and desperate act to recover lost connection. There is an overwhelming sense of being hemmed-in by impassable open spaces. The wide snowy vistas are barriers in disguise. The probability of death on the farm is weighed-up against the certain death of exposure on the outside. Isolation is the dominant motif. There are constant reminders of the cold. Feet sinking into deep drifts. Walking tracks are quickly covered by fresh snowfall. Even the underfloor heating in the new house. The only time anyone walks any real distance, they encounter a gathering of knackered looking horses struggling to survive. They turn back.

In a 2019 interview Sigurdardóttir spoke of her desire to combine elements of crime and horror in a single novel. This book demonstrates how thin that line can be. Read more »

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Sherman J. Clark

There are many reasons, moral and prudential, not to be cruel. I would like to add another. Cruelty is bad for us—not just bad for those to whom we are cruel but also bad for those of us in whose name and for whose seeming benefit cruelty is committed. Consider our vast system of jails and prisons. Much has been said about the moral injustice of mass incarceration and about the staggering waste of human and financial resources it entails. My concern is different but connected: the cruelty we commit or tolerate also harms those of us on whose behalf it is carried out. It does so by stunting our growth.

To sustain such cruelty, we must look away—cultivate a kind of blindness. We must also cultivate a kind of cognitive blurriness, accepting or tolerating tenuous explanations and justifications for what at some level we know is not OK. And in cultivating that blindness and blurriness, we may make ourselves less able to live well. It is hard to navigate the world and life well with your eyes half closed and your internal bullshit meter set to “comfort mode.”

We’ve gotten good at not seeing what’s done in our name. Nearly two million people are incarcerated in America’s prisons and jails. They endure overcrowding, violence, medical neglect, and conditions that international observers regularly condemn. We know this, dimly. The information is available, documented in reports and investigations and lawsuits. But we have developed an elaborate architecture of avoidance—geographic, psychological, linguistic—to keep this knowledge at arm’s length. We put prisons in the remote regions of our states, and prisoners in the remote regions of our minds. And we try not to think about it.

This turning away from the cruelty of mass incarceration is only one of many ways we hide from our indirect complicity in or connection to things that should trouble us. Prisons are just one particularly vivid example of ethical evasions that can dim our sight, cloud our minds, and thus in inhibit our ability to learn and growth and thrive. We perform similar gymnastics of avoidance everywhere: treating financial returns as somehow separate from their real-world origins; planning out cities so that the rich often need not even see the poor; ignoring the long-term consequences of political decisions. Each of these distances—financial, geographical, temporal—may appear natural, even inevitable, just how things work. But they’re architectures we’ve built, or at least maintain, to spare ourselves from seeing clearly. Read more »

by Lei Wang

My best friend sometimes requests on first dates that they both get there 45 minutes early and work at the coffeeshop or bar together in silence; if her date doesn’t have their own quiet work to do, they can otherwise entertain themselves or just watch her write. But Do Not Disturb. She needs to write her novel in peace, but also she needs a supervising adult to help her write, please.

I am surprised at how many strangers say yes to and then obey this invitation (out of dozens, she has only gotten one outright refusal and one who didn’t take her seriously and tried to distract her, which didn’t end well for him). Then again, maybe everybody hustling in L.A. just wants to parallel play.

I have not employed romantic prospects in quite this way, but have certainly otherwise elicited lovers as pawns for productivity hacking. I asked a delicious baritone to withhold a voice note from me until I sent an important e-mail I had been delaying for months. For a recent deadline, an online-only paramour slowly revealed himself to me through a series of extraordinarily tasteful photos—each photo a treat for meeting a specific writing goal. But we somehow fell off before my due date, and so I never got to the final reward.

Alas, I wish I could be intrinsically motivated by the work itself, but it seems I keep needing to resort to low-brow dopamine exploits to do the things I actually truly want to do. According to Gretchen Rubin’s personality theory of the Four Tendencies, I am hopelessly an Obliger: someone who meets outer expectations, but resists inner expectations. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Uncharted Waters. July, 2018.

Digital photograph.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.