Jerry Seinfeld is fond of comparing jokes to machines: Jokes are tiny intricately crafted machines, where all the parts fit neatly and precisely together, moving in precise, if sometimes surprising, fashion. Last summer I decided to pit Seinfeld against the precisest (is that even a word?), most super-modern, and biggest intricate machine I could think of, GPT-3. You may have heard of it, it’s an AI engine. As you may know, AI engines are not at all like automobile engines. They’re not mechanical devices. They’re, well, you know, they live up in the cloud, where all the super-modern high-tech gizmos and gadgets hang out, or whatever it is that they do while secretly plotting to take over the world.

Seinfeld tells a joke

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Let’s start with something we know, Jerry Seinfeld. Here’s his very first television appearance. It is from 1977 on Celebrity Cabaret, a nationally syndicated show. He’s doing a bit that involves the Roosevelt Island tramway. You know what that is? If you’re familiar with the New York City area you do. Otherwise, it may be something of a mystery.

But first things first. Here’s the video (joke starts at about 0:29):

I’m not sure he’d get away with the word “ghetto” these days, but back in the 1970s it was A-OK. This particular sketchy part of town is the South Bronx which, as my colleague Michael Liss reminded me, was the setting for a 1981 crime drama, Fort Apache, The Bronx. It’s also the setting for the 2016 Netflix series, The Get Down, about the early days of hip-hop. Read more »

We arrived in Berkeley and found it to be a pleasant place to live. I always have a partiality for small university towns that are culturally and politically alive. And yet Berkeley is not far from a thriving major city (San Francisco—“the unfettered city/resounds with hedonistic glee”, as Vikram Seth describes it in his verse-novel The Golden Gate) on the one hand, and from wide-open spaces on the other. Nature in Berkeley itself is quite beautiful, nestled as it is on a leafy hillside and facing an ocean and its bay, with gorgeous sunsets over the Golden Gate Bridge (on days when it is not shrouded by the mysterious fog—which appears almost as a character in San Francisco noir, like in the crime novels of Dashiell Hammett). Once driving in the dense fog in a winding street in the Berkeley hills I missed a turn and lost my way; I fondly remembered that famous scene in Fellini’s semi-autobiographical film Amarcord, where one winter-day in Rimini, his childhood town, the fog shrouds everything, the piazza disappears, and the grandpa loses his way home.

We arrived in Berkeley and found it to be a pleasant place to live. I always have a partiality for small university towns that are culturally and politically alive. And yet Berkeley is not far from a thriving major city (San Francisco—“the unfettered city/resounds with hedonistic glee”, as Vikram Seth describes it in his verse-novel The Golden Gate) on the one hand, and from wide-open spaces on the other. Nature in Berkeley itself is quite beautiful, nestled as it is on a leafy hillside and facing an ocean and its bay, with gorgeous sunsets over the Golden Gate Bridge (on days when it is not shrouded by the mysterious fog—which appears almost as a character in San Francisco noir, like in the crime novels of Dashiell Hammett). Once driving in the dense fog in a winding street in the Berkeley hills I missed a turn and lost my way; I fondly remembered that famous scene in Fellini’s semi-autobiographical film Amarcord, where one winter-day in Rimini, his childhood town, the fog shrouds everything, the piazza disappears, and the grandpa loses his way home.

The President and the Provost have both been urging a whitewashing (if I can use this term) of the College’s history by such measures as removing Huxley’s name and bust from one of Imperial’s most prominent buildings. As I explained earlier, they attempted to accomplish this using a deeply flawed process. A History Group lacking in any higher level expertise in Huxley’s own areas of biology and palaeontology was set up, with the College archivist restricted to a consultative role, as was the Imperial faculty member best qualified to comment on historical matters. Two outside historians were consulted, but their areas of expertise did not really include Huxley.1 Adrian Desmond, Huxley’s biographer, was consulted but as I documented in my earlier article, his unambiguous vindication of Huxley was completely ignored. In October (revised version November), the

The President and the Provost have both been urging a whitewashing (if I can use this term) of the College’s history by such measures as removing Huxley’s name and bust from one of Imperial’s most prominent buildings. As I explained earlier, they attempted to accomplish this using a deeply flawed process. A History Group lacking in any higher level expertise in Huxley’s own areas of biology and palaeontology was set up, with the College archivist restricted to a consultative role, as was the Imperial faculty member best qualified to comment on historical matters. Two outside historians were consulted, but their areas of expertise did not really include Huxley.1 Adrian Desmond, Huxley’s biographer, was consulted but as I documented in my earlier article, his unambiguous vindication of Huxley was completely ignored. In October (revised version November), the  I am a modern-day scrapbooker. Which is to say that, like scrapbookers and notebook keepers across the ages, I am incessantly recording: things I have read, things I want to read, ideas I have come across or had, ways I want to be or to look, memorabilia from places I have been or want to go, inspiring or thought-provoking words, song lyrics, images, film clips, you name it. Like those who went before me, I record things in physical notebooks, but – and this is the new thing – my canvas is far larger than this original form. Digital photo albums, the iPhone ‘notes’ pad, emails to self,

I am a modern-day scrapbooker. Which is to say that, like scrapbookers and notebook keepers across the ages, I am incessantly recording: things I have read, things I want to read, ideas I have come across or had, ways I want to be or to look, memorabilia from places I have been or want to go, inspiring or thought-provoking words, song lyrics, images, film clips, you name it. Like those who went before me, I record things in physical notebooks, but – and this is the new thing – my canvas is far larger than this original form. Digital photo albums, the iPhone ‘notes’ pad, emails to self,

I used to sit in class with songs in my head, loud enough to feel their beat in my fingertips. I used to blare Adele instead of listening to my teacher. I would sing voicelessly with Hozier while my classmates read a paragraph out loud. Passenger, P!nk, The Lumineers, Steven Sondheim. Billie Eilish, too, though not openly as it’s not cool to like anything that’s cool.

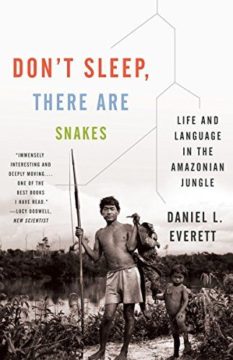

I used to sit in class with songs in my head, loud enough to feel their beat in my fingertips. I used to blare Adele instead of listening to my teacher. I would sing voicelessly with Hozier while my classmates read a paragraph out loud. Passenger, P!nk, The Lumineers, Steven Sondheim. Billie Eilish, too, though not openly as it’s not cool to like anything that’s cool. Daniel Everett’s 2008 book Don’t Sleep: There are Snakes tells two stories of loss. First, it tells how the young missionary linguist, who had been trained to analyse languages at the Summer Institute (now

Daniel Everett’s 2008 book Don’t Sleep: There are Snakes tells two stories of loss. First, it tells how the young missionary linguist, who had been trained to analyse languages at the Summer Institute (now

Lots of things don’t exist. Bigfoot, a planet between Uranus and Neptune, yummy gravel, plays written by Immanuel Kant, the pile of hiking shoes stacked on your head — so many things, all of them not existing. Maybe there are more things that don’t exist than we have names for. After all, there are more real objects than we have names for. No one has named every individual squid, nor every rock on Mars, nor every dream you’ve ever had. The list of existing things consists mostly of nameless objects, it seems.

Lots of things don’t exist. Bigfoot, a planet between Uranus and Neptune, yummy gravel, plays written by Immanuel Kant, the pile of hiking shoes stacked on your head — so many things, all of them not existing. Maybe there are more things that don’t exist than we have names for. After all, there are more real objects than we have names for. No one has named every individual squid, nor every rock on Mars, nor every dream you’ve ever had. The list of existing things consists mostly of nameless objects, it seems.

A couple of weeks ago, the main healthcare provider in my city sent me a newsletter. One of the items was a brief blurb about how laughter is good for you, with a link to “Learn More About the Benefits of Laughter.” No! If you think laughter is good for our health, link to a video of a cat riding a Roomba or bear cubs on a hammock. I might click through to see those; I might even laugh. I’m not going to look at an article about the benefits of laughter, because it will become another open tab, a nagging chore, an obligation that stands between me and the conditions for laughter.

A couple of weeks ago, the main healthcare provider in my city sent me a newsletter. One of the items was a brief blurb about how laughter is good for you, with a link to “Learn More About the Benefits of Laughter.” No! If you think laughter is good for our health, link to a video of a cat riding a Roomba or bear cubs on a hammock. I might click through to see those; I might even laugh. I’m not going to look at an article about the benefits of laughter, because it will become another open tab, a nagging chore, an obligation that stands between me and the conditions for laughter. Sughra Raza. Mood … , Our Pale Blue Dot.

Sughra Raza. Mood … , Our Pale Blue Dot.