by Martin Butler

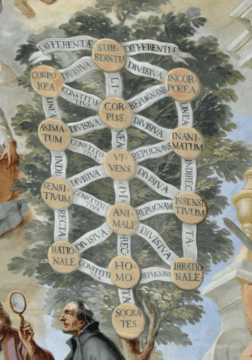

Although by no means the only ones, two models of human beings and their relation to society are prominent in modern social and political thought. At first glance they seem incompatible, but I want to sketch them out and start to establish how they might plausibly be made to fit together.

Although by no means the only ones, two models of human beings and their relation to society are prominent in modern social and political thought. At first glance they seem incompatible, but I want to sketch them out and start to establish how they might plausibly be made to fit together.

The first one I’ll call the cultural model. It is based on the truism that human beings are the products of the particular traditions and histories of their society, and is a relativistic view since it allows for no trans-cultural standards against which cultures can be compared. The key features of this model are its historical nature and the fact that it is essentially social, in that individuals can only be fully understood with reference to the culture in which they were raised. All cultures have a history and evolve over time, and cultures only exist in groups of individuals; you can’t have your own personal culture.

To fully understand a culture it’s necessary to get to know the specific patterns of life within it, and these can’t be captured by abstractions or generalisations. You might, for example, say that culture X is Christian but that doesn’t actually tell you very much about how life is lived in that culture. This does not mean that human beings are completely malleable since we can accept that human nature exerts limits on what it’s possible for a person to be, and of course individuals within a culture can be very different. However, according to this model, culture leaves a major and indelible mark. There will, of course, be huge variation, but I think it’s important to note that typically gender and gender roles, bonds of kinship, religious belief (or lack of it) and rituals of various kinds are pivotal in shaping the identity of most cultures. The stereotypical image of a traditional culture is ethnically homogeneous with a well-established shared way of life, strong bonds of kinship and well-defined gender roles, all of which are supported by a set of widely held beliefs (usually religious) along with the general acceptance of a particular historical narrative.

The second model is the enlightenment model. The ideas that form the core of this model have been around for a long time but they found a particularly clear expression in European philosophy of the 18th century. This model gives centre stage to reason and free-will, and sees individuals and their rights as the starting point and building blocks of society, rather than the products of society. Read more »

Anneliese Hager. Untitled. ca. 1940-1950

Anneliese Hager. Untitled. ca. 1940-1950

“

“ In recent years the institution in England I have visited frequently is London School of Economics (LSE), in 1998 as a STICERD Distinguished Visitor, and in 2010-11 as a BP Centennial Professor (this was shortly after the disastrous BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, so I hesitated telling people about my designation), and numerous times as visitor just for a few days. In recent times most of my interactions there have been with the development economists Tim Besley and Maitreesh Ghatak in the Economics Department and with Robert Wade, economist Jean-Paul Faguet and some years earlier, John Harriss (the political sociologist specializing in India) in the International Development Department. In recent years, apart from departmental seminars, I also gave two somewhat formal public lectures in a large LSE auditorium, once on China and India, and the other time on A New Agenda for Global Labor.

In recent years the institution in England I have visited frequently is London School of Economics (LSE), in 1998 as a STICERD Distinguished Visitor, and in 2010-11 as a BP Centennial Professor (this was shortly after the disastrous BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, so I hesitated telling people about my designation), and numerous times as visitor just for a few days. In recent times most of my interactions there have been with the development economists Tim Besley and Maitreesh Ghatak in the Economics Department and with Robert Wade, economist Jean-Paul Faguet and some years earlier, John Harriss (the political sociologist specializing in India) in the International Development Department. In recent years, apart from departmental seminars, I also gave two somewhat formal public lectures in a large LSE auditorium, once on China and India, and the other time on A New Agenda for Global Labor. Francis Fukuyama does not mind having to play defense. Recognizing that the problems plaguing liberal societies result in no small part from the flaws and weaknesses of liberalism itself, he argues in Liberalism and its Discontents (Profile Books: 2022) that the response to these problems, all said and done, is liberalism. This requires some courage: three decades ago, Fukuyama may have captured the spirit of the age, but the spirit has grown impatient with liberalism as of late. Fukuyama, however, does not think of it as a worn-out ideal. He has taken note of right-wing assaults, as well as progressive criticisms that suggest a need to go beyond it; and his verdict is that any attempt at improvement will either stay in a liberal orbit or lead to political decay. Liberalism is still the best we have got.

Francis Fukuyama does not mind having to play defense. Recognizing that the problems plaguing liberal societies result in no small part from the flaws and weaknesses of liberalism itself, he argues in Liberalism and its Discontents (Profile Books: 2022) that the response to these problems, all said and done, is liberalism. This requires some courage: three decades ago, Fukuyama may have captured the spirit of the age, but the spirit has grown impatient with liberalism as of late. Fukuyama, however, does not think of it as a worn-out ideal. He has taken note of right-wing assaults, as well as progressive criticisms that suggest a need to go beyond it; and his verdict is that any attempt at improvement will either stay in a liberal orbit or lead to political decay. Liberalism is still the best we have got. Every now and then, a nation becomes modern. Greeks and Poles and Russians were modern, for a time. Now it’s the Ukrainians’ turn.

Every now and then, a nation becomes modern. Greeks and Poles and Russians were modern, for a time. Now it’s the Ukrainians’ turn. As the January 6th hearings continue and Americans watch

As the January 6th hearings continue and Americans watch  I knew it was coming, yet I was still surprised when it hit my classroom.

I knew it was coming, yet I was still surprised when it hit my classroom.  I think a lot about the fate of human civilization these days.

I think a lot about the fate of human civilization these days. Lorenza Böttner. Face Art, 1983.

Lorenza Böttner. Face Art, 1983.