by Ashutosh Jogalekar

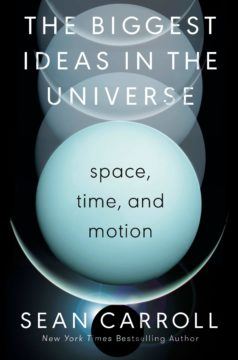

Physicists writing books for the public have faced a longstanding challenge. Either they can write purely popular accounts that explain physics through metaphors and pop culture analogies but then risk oversimplifying key concepts, or they can get into a great deal of technical detail and risk making the book opaque to most readers without specialized training. All scientists face this challenge, but for physicists it’s particularly acute because of the mathematical nature of their field. Especially if you want to explain the two towering achievements of physics, quantum mechanics and general relativity, you can’t really get away from the math. It seems that physicists are stuck between a rock and a hard place: include math and, as the popular belief goes, every equation risks cutting their readership by half or, exclude math and deprive readers of a deeper understanding. The big question for a physicist who wants to communicate the great ideas of physics to a lay audience without entirely skipping the technical detail thus is, is there a middle ground?

Physicists writing books for the public have faced a longstanding challenge. Either they can write purely popular accounts that explain physics through metaphors and pop culture analogies but then risk oversimplifying key concepts, or they can get into a great deal of technical detail and risk making the book opaque to most readers without specialized training. All scientists face this challenge, but for physicists it’s particularly acute because of the mathematical nature of their field. Especially if you want to explain the two towering achievements of physics, quantum mechanics and general relativity, you can’t really get away from the math. It seems that physicists are stuck between a rock and a hard place: include math and, as the popular belief goes, every equation risks cutting their readership by half or, exclude math and deprive readers of a deeper understanding. The big question for a physicist who wants to communicate the great ideas of physics to a lay audience without entirely skipping the technical detail thus is, is there a middle ground?

Over the last decade or so there have been a few books that have in fact tried to tread this middle ground. Perhaps the most ambitious was Roger Penrose’s “The Road to Reality” which tried to encompass, in more than 800 pages, almost everything about mathematics and physics. Then there’s the “Theoretical Minimum” series by Leonard Susskind and his colleagues which, in three volumes (and an upcoming fourth one on general relativity) tries to lay down the key principles of all of physics. But both Penrose and Susskind’s volumes, as rewarding as they are, require a substantial time commitment on the part of the reader, and both at one point become comprehensible only to specialists.

If you are trying to find a short treatment of the key ideas of physics that is genuinely accessible to pretty much anyone with a high school math background, you would be hard-pressed to do better than Sean Carroll’s upcoming “The Biggest Ideas in the Universe”. Since I have known him a bit on social media for a while, I will refer to Sean by his first name. “The Biggest Ideas in the Universe” is based on a series of lectures that Sean gave during the pandemic. The current volume is the first in a set of three and deals with “space, time and motion”. In short, it aims to present all the math and physics you need to know for understanding Einstein’s special and general theories of relativity. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Self-portrait in Reflected Morning Light, August 2, 2022.

Sughra Raza. Self-portrait in Reflected Morning Light, August 2, 2022.

If philosophy is not only an academic, theoretical discipline but a way of life, as many Ancient Greek and Roman philosophers thought, one way of evaluating a philosophy is in terms of the kind of life it entails.

If philosophy is not only an academic, theoretical discipline but a way of life, as many Ancient Greek and Roman philosophers thought, one way of evaluating a philosophy is in terms of the kind of life it entails.

It’s still such a strange time as regards the Covid-19 pandemic. Most governments have lifted restrictions and lockdowns. However, new variants are still emerging and far too few people have been vaccinated globally to lend confidence for the health crisis’s resolution. With this in mind, I’ve been reading

It’s still such a strange time as regards the Covid-19 pandemic. Most governments have lifted restrictions and lockdowns. However, new variants are still emerging and far too few people have been vaccinated globally to lend confidence for the health crisis’s resolution. With this in mind, I’ve been reading  The Welcome Center museum isn’t exceptionally well-known. I often hear variations of the same phrase: “Oh, I’ve been coming to Breckenridge for years and never knew there was a museum back here!” It does get a lot of foot traffic, though, because (as its name implies) it is in the back of the Welcome Center building.

The Welcome Center museum isn’t exceptionally well-known. I often hear variations of the same phrase: “Oh, I’ve been coming to Breckenridge for years and never knew there was a museum back here!” It does get a lot of foot traffic, though, because (as its name implies) it is in the back of the Welcome Center building.

After LSE I have seen Jean Drèze mostly in India, usually in conferences in Delhi and Kolkata, and at Amartya Sen’s home in Santiniketan (where he used to stay whenever the two of them were writing books together). The Kolkata conferences were the annual ones that Amartya-da used to organize for some years, held usually at the Taj Bengal five-star hotel, which Jean would refuse to stay in. While others would take the 2-hour flight from Delhi to Kolkata, Jean would take the 24-hour train in the crowded second-class compartment. Then he’d call me and often stay with me in my Kolkata apartment. If Kalpana was around and it was winter she’d warm the bath water for him and arrange a comfortable raised bed for him; but Jean would refuse even those minor luxuries, and insist on taking cold showers and sleeping on the floor.

After LSE I have seen Jean Drèze mostly in India, usually in conferences in Delhi and Kolkata, and at Amartya Sen’s home in Santiniketan (where he used to stay whenever the two of them were writing books together). The Kolkata conferences were the annual ones that Amartya-da used to organize for some years, held usually at the Taj Bengal five-star hotel, which Jean would refuse to stay in. While others would take the 2-hour flight from Delhi to Kolkata, Jean would take the 24-hour train in the crowded second-class compartment. Then he’d call me and often stay with me in my Kolkata apartment. If Kalpana was around and it was winter she’d warm the bath water for him and arrange a comfortable raised bed for him; but Jean would refuse even those minor luxuries, and insist on taking cold showers and sleeping on the floor. A little while ago my friend Bethany requested that I write an essay on the following topic: “Can/should pedantry be reconstituted as a virtue, maybe particularly for women.” I filed it away on my list of possible future essay ideas, but like a

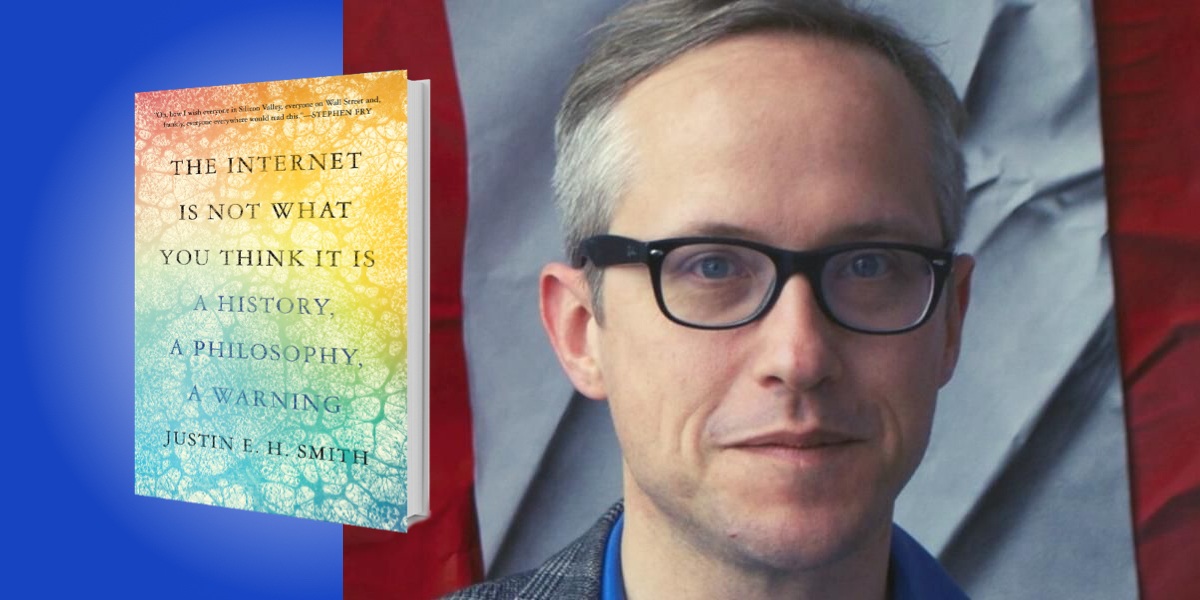

A little while ago my friend Bethany requested that I write an essay on the following topic: “Can/should pedantry be reconstituted as a virtue, maybe particularly for women.” I filed it away on my list of possible future essay ideas, but like a  Justin E. H. Smith’s recent book,

Justin E. H. Smith’s recent book,  I’m not sure what Americans were like in the 18th and 19th century, but they have to have been a lot tougher, less whining, less self-important and paradoxically more exceptional without thinking they were exceptional than Americans of today.

I’m not sure what Americans were like in the 18th and 19th century, but they have to have been a lot tougher, less whining, less self-important and paradoxically more exceptional without thinking they were exceptional than Americans of today.

Sughra Raza. Untitled, ca 2008.

Sughra Raza. Untitled, ca 2008.