by David J. Lobina

‘It should be by now common knowledge that the “cognitive revolution” that gripped the fields of psychology and philosophy in the 1950s and 60s originated in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where a particular intellectual milieu was then forming around Noam Chomsky.’ Or so I started an article of mine a few years ago (it was never published, though a butchered version ended up here).

Fine, I continued, Chomsky might have been primus inter pares in this sphere, but what about the philosopher Jerry Fodor, perhaps second-best among this group of cognitive scientists, as they were to be known from then on? What about Fodor indeed. In the rest of the piece, I tried to explain why Fodor’s contributions may be more enduring in the long run. That was on the occasion of Fodor having been honoured with a festschrift of sorts at the time, a book that contains a piece of my own, in fact.

I want to take a slightly different approach here – a more personal one, in a way – as I would like to make a point born from the perception that Fodor is often too easily (or too quickly) dismissed. This might sound rather counterintuitive to some, and it is certainly not the case that Fodor’s ideas haven’t received plenty of attention ever since he started publishing in the 1960s or so, including outside academia, most notable in the London Review of Books (Darwin was said to have got something wrong once). No-one would deny he has been a central figure in cognitive science. But it is also true that the attitudes of some scholars towards Fodor’s work, and towards him in fact, have sometimes been rather cavalier. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Chughtai In Shabnam’s Living Room, November, 2022.

Sughra Raza. Chughtai In Shabnam’s Living Room, November, 2022.

I moved to Berlin in 1984, but have rarely written about my experiences living in a foreign country; now that I think about it, it occurs to me that I lived here as though in exile those first few years, or rather as though I’d been banished, as though it hadn’t been my own free will to leave New York. It’s difficult to speak of the time before the Wall fell without falling into cliché—difficult to talk about the perception non-Germans had of the city, for decades, because in spite of the fascination Berlin inspired, it was steeped in the memory of industrialized murder and lingering fear and provoked a loathing that was, for some, quite visceral. Most of my earliest friends were foreigners, like myself; our fathers had served in World War II and were uncomfortable that their children had wound up in former enemy territory, but my Israeli and other Jewish friends had done the unthinkable: they’d moved to the land that had nearly extinguished them, learned to speak in the harsh consonants of the dreaded language, and betrayed their family and its unspeakable sufferings, or so their parents claimed. We were drawn to the stark reality of a walled-in, heavily guarded political enclave, long before the reunited German capital became an international magnet for start-ups and so-called creatives. We were the generation that had to justify itself for being here. It was hard not to be haunted by the city’s past, not to wonder how much of the human insanity that had taken place here was somehow imbedded in the soil—or if place is a thing entirely indifferent to us, the Earth entirely indifferent to the blood spilled on its battlegrounds.

I moved to Berlin in 1984, but have rarely written about my experiences living in a foreign country; now that I think about it, it occurs to me that I lived here as though in exile those first few years, or rather as though I’d been banished, as though it hadn’t been my own free will to leave New York. It’s difficult to speak of the time before the Wall fell without falling into cliché—difficult to talk about the perception non-Germans had of the city, for decades, because in spite of the fascination Berlin inspired, it was steeped in the memory of industrialized murder and lingering fear and provoked a loathing that was, for some, quite visceral. Most of my earliest friends were foreigners, like myself; our fathers had served in World War II and were uncomfortable that their children had wound up in former enemy territory, but my Israeli and other Jewish friends had done the unthinkable: they’d moved to the land that had nearly extinguished them, learned to speak in the harsh consonants of the dreaded language, and betrayed their family and its unspeakable sufferings, or so their parents claimed. We were drawn to the stark reality of a walled-in, heavily guarded political enclave, long before the reunited German capital became an international magnet for start-ups and so-called creatives. We were the generation that had to justify itself for being here. It was hard not to be haunted by the city’s past, not to wonder how much of the human insanity that had taken place here was somehow imbedded in the soil—or if place is a thing entirely indifferent to us, the Earth entirely indifferent to the blood spilled on its battlegrounds.

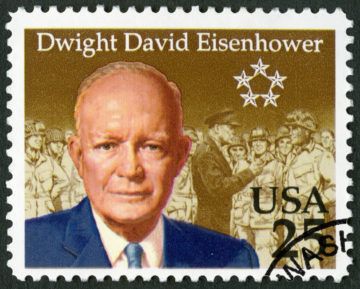

A Republican used to be someone like Dwight Eisenhower, a moderate who worked well with the opposing party, even meeting weekly with their leadership in the Senate and House. Eisenhower expanded social security benefits and, against the more right-wing elements of his party, appointed Earl Warren to be the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Warren, you’ll remember, wrote the majority opinion of Brown v Board of Education, Miranda v Arizona, and Loving v Virginia. If Dwight Eisenhower were alive today, he would be branded a RINO and a communist by his own party. I suspect he would become registered as unaffiliated.

A Republican used to be someone like Dwight Eisenhower, a moderate who worked well with the opposing party, even meeting weekly with their leadership in the Senate and House. Eisenhower expanded social security benefits and, against the more right-wing elements of his party, appointed Earl Warren to be the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Warren, you’ll remember, wrote the majority opinion of Brown v Board of Education, Miranda v Arizona, and Loving v Virginia. If Dwight Eisenhower were alive today, he would be branded a RINO and a communist by his own party. I suspect he would become registered as unaffiliated.

It’s not about dying, really—it’s about knowing you’re about to die. Not in the abstract way that we haphazardly confront our own mortality as we reach middle age and contemplate getting old. And not even in the way (I imagine) that someone with a terminal diagnosis might think about death—sooner than expected and no longer theoretical. It’s much more immediate than that.

It’s not about dying, really—it’s about knowing you’re about to die. Not in the abstract way that we haphazardly confront our own mortality as we reach middle age and contemplate getting old. And not even in the way (I imagine) that someone with a terminal diagnosis might think about death—sooner than expected and no longer theoretical. It’s much more immediate than that.

Carlos Donjuan. Together Alone.

Carlos Donjuan. Together Alone.

A philosopher and a stand-up comedian walk into a bar…the beginning of a joke? Or perhaps a history of humanity from the margins. The philosopher and the stand-up comedian are two figures that keep reappearing across the ages, cutting familiar silhouettes of odd bodies making odd claims about the world and its inhabitants.

A philosopher and a stand-up comedian walk into a bar…the beginning of a joke? Or perhaps a history of humanity from the margins. The philosopher and the stand-up comedian are two figures that keep reappearing across the ages, cutting familiar silhouettes of odd bodies making odd claims about the world and its inhabitants.