by Joseph Shieber

Suppose you had a friend whom you knew to be a lover of good coffee. You ask him how he likes his coffee machine and he replies that it’s okay. He emphasizes that one of the best features of the coffee machine is that it’s extremely reliable; each cup of coffee is the same as the last.

Curious, you ask your friend to brew a cup for you. After taking a sip, you exclaim, “Ugh, this tastes awful.”

“Yes,” your friend replies, “but at least it’s consistent.”

You’d likely think that such a response was crazy! Presumably, if given a choice between a machine that consistently produces bad cups of coffee and a machine that is inconsistent, but that at least occasionally produces good cups of coffee, anyone would choose the inconsistent machine. At least it gives you the CHANCE of getting a good cup of coffee!

Despite the seeming sensibleness of this view, it is surprisingly hard to keep its lesson in mind – for me no less than for others.

I was mindful of this as I read Liza Batkin’s essay, “The Kingdom of Antonin Scalia,” in The New Yorker.

Batkin’s work is only the latest in a long line of think-pieces charging that the Supreme Court’s now-ascendent conservatives aren’t true to their own espoused doctrines, but only apply those doctrines consistently when they yield their preferred political outcomes (examples of this style of piece go back, in my recollection, at least as far as Bush v Gore). Read more »

First, because Moses, or the prophet Musa as we know him in the Quran, is an unusual hero— a newborn all on his own, swaddled and floating in a papyrus basket on the Nile— my brothers and I couldn’t get enough of his story as children. Second, it is also a story of siblings: his sister keeps an eye on him, walking along the river as the baby drifts in the reeds farther and farther away from home, his brother, the prophet Harun accompanies him through many crucial journeys later in life, another reason the story was relatable. Returning to the narration as a young woman, a mother, I found myself more interested in the heroines in the story: Musa’s birth-mother whose maternal instinct and faith are tested in a time of persecution, the Pharaoh’s wife Asiya who adopts the foundling as her own, confronting her megalomaniac husband’s ire and successfully raising a child of slaves and the prophesied contender to the pharaoh’s power under his own roof. As a diaspora writer, especially one wielding the colonizer’s tongue and negotiating the contradictory gifts of language, I have yet again been drawn to Musa. He is an outsider and an insider— one who carries a “knot on his tongue”— the burden of interpreting and speaking, not entirely out of choice, to radically different entities: God, the Pharaoh and his own people. Among the myriad facets of the legend, the most enduring is the innocence at the heart of his mythos, the exoteric quality of wisdom explored beautifully in mystic writings and poetry as a complementary aspect of the esoteric.

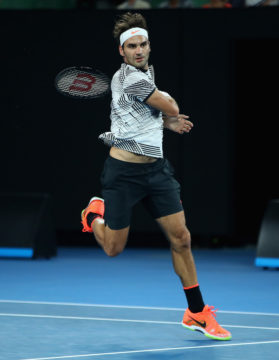

First, because Moses, or the prophet Musa as we know him in the Quran, is an unusual hero— a newborn all on his own, swaddled and floating in a papyrus basket on the Nile— my brothers and I couldn’t get enough of his story as children. Second, it is also a story of siblings: his sister keeps an eye on him, walking along the river as the baby drifts in the reeds farther and farther away from home, his brother, the prophet Harun accompanies him through many crucial journeys later in life, another reason the story was relatable. Returning to the narration as a young woman, a mother, I found myself more interested in the heroines in the story: Musa’s birth-mother whose maternal instinct and faith are tested in a time of persecution, the Pharaoh’s wife Asiya who adopts the foundling as her own, confronting her megalomaniac husband’s ire and successfully raising a child of slaves and the prophesied contender to the pharaoh’s power under his own roof. As a diaspora writer, especially one wielding the colonizer’s tongue and negotiating the contradictory gifts of language, I have yet again been drawn to Musa. He is an outsider and an insider— one who carries a “knot on his tongue”— the burden of interpreting and speaking, not entirely out of choice, to radically different entities: God, the Pharaoh and his own people. Among the myriad facets of the legend, the most enduring is the innocence at the heart of his mythos, the exoteric quality of wisdom explored beautifully in mystic writings and poetry as a complementary aspect of the esoteric. The one regret of my life so far is never having seen Roger Federer play tennis in person. As Federer announced his retirement this year, I’ll never have the chance. The closest I came was the summer of 2017: I was in Italy and planned on flying to Stuttgart to see Federer play in a grass court tournament as preparation for Wimbledon. A few weeks before I was set to leave, I applied for a job at an English language school, largely at the behest of my girlfriend, who was unhappy with the fact that I was “studying” Italian in the mornings and flâning the streets in the afternoons, all while she spent long days toiling away as an unpaid intern in a law office, a common situation in Italy. I didn’t expect to get the job—I had little experience and no real credentials—but I would soon learn that neither of these things mattered, superseded as they were by my being a native speaker. I got the job and had to cancel my trip.

The one regret of my life so far is never having seen Roger Federer play tennis in person. As Federer announced his retirement this year, I’ll never have the chance. The closest I came was the summer of 2017: I was in Italy and planned on flying to Stuttgart to see Federer play in a grass court tournament as preparation for Wimbledon. A few weeks before I was set to leave, I applied for a job at an English language school, largely at the behest of my girlfriend, who was unhappy with the fact that I was “studying” Italian in the mornings and flâning the streets in the afternoons, all while she spent long days toiling away as an unpaid intern in a law office, a common situation in Italy. I didn’t expect to get the job—I had little experience and no real credentials—but I would soon learn that neither of these things mattered, superseded as they were by my being a native speaker. I got the job and had to cancel my trip.

“My account omitted many very serious incidents,” writes Bertrand Roehner, the French historiographer whose analysis on statistics about violence in post-war Japan I used in my Graywolf Nonfiction Prize memoir, Black Glasses Like Clark Kent. He began emailing me at this September about a six-volume, two thousand page report concerning Japanese casualties during the Occupation that has just been released in Japanese after sixty years of suppression.

“My account omitted many very serious incidents,” writes Bertrand Roehner, the French historiographer whose analysis on statistics about violence in post-war Japan I used in my Graywolf Nonfiction Prize memoir, Black Glasses Like Clark Kent. He began emailing me at this September about a six-volume, two thousand page report concerning Japanese casualties during the Occupation that has just been released in Japanese after sixty years of suppression.

I like to vote in person on Election Day. I’m sentimental that way. My polling precinct is at the local elementary school. So last Tuesday, I woke up early, dressed and got out the door in a rush, and arrived to find not the expected pastiche of cardboard candidate signs and nagging pamphleteers, but rather a playground full of 2nd graders.

I like to vote in person on Election Day. I’m sentimental that way. My polling precinct is at the local elementary school. So last Tuesday, I woke up early, dressed and got out the door in a rush, and arrived to find not the expected pastiche of cardboard candidate signs and nagging pamphleteers, but rather a playground full of 2nd graders.

I’m not sold on longtermism myself, but its proponents sure have my sympathy for the eagerness with which its opponents mine their arguments for repugnant conclusions. The basic idea, that we ought to do more for the benefit of future lives than we are doing now, is often seen as either ridiculous or dangerous.

I’m not sold on longtermism myself, but its proponents sure have my sympathy for the eagerness with which its opponents mine their arguments for repugnant conclusions. The basic idea, that we ought to do more for the benefit of future lives than we are doing now, is often seen as either ridiculous or dangerous. Sughra Raza. Valparaiso Expressions. Chile, November 2017.

Sughra Raza. Valparaiso Expressions. Chile, November 2017.

Climate change and covid are revealing an ongoing inability for our society to make wise decisions in the face of calamity, which may be leading us to a collapse of our civilization. Perhaps if we accept (or just believe) that we’re nearing the end, we can shift our priorities enough to usher in a more peaceful and equitable denouement.

Climate change and covid are revealing an ongoing inability for our society to make wise decisions in the face of calamity, which may be leading us to a collapse of our civilization. Perhaps if we accept (or just believe) that we’re nearing the end, we can shift our priorities enough to usher in a more peaceful and equitable denouement.