by Sarah Firisen

For a long time, an accepted principle of corporate life has been that to take advantage of spontaneous ideation to drive innovation, people need to be in the same physical space. To encourage innovation, Apple, the accepted exemplar of an innovative company, built its headquarters in such a way as to try to spark these innovative interactions; “It’s hoped that by housing so many employees in one facility, workers will be more likely to build relationships with those outside of their team, share ideas with co-workers with different specialties and learn about opportunities to collaborate.”

For a long time, an accepted principle of corporate life has been that to take advantage of spontaneous ideation to drive innovation, people need to be in the same physical space. To encourage innovation, Apple, the accepted exemplar of an innovative company, built its headquarters in such a way as to try to spark these innovative interactions; “It’s hoped that by housing so many employees in one facility, workers will be more likely to build relationships with those outside of their team, share ideas with co-workers with different specialties and learn about opportunities to collaborate.”

Another principle, as this McKinsey piece claims, is that “Innovation is a team sport….when it comes to innovation, it is rare to see individuals who possess the full range of skills needed to lead an initiative.” And, at least until March 2020, the assumption was that the only successful way to collaborate creatively was in person. The brainstorming workshop, or team whiteboarding off-site, was something that most of us in white-collar jobs have been part of in some form or at some time.

At this point, it’s not news that many, maybe even most, of the white-collar workers who have been able to work remotely throughout the pandemic don’t want to return to the office. I’ve written about the, perhaps surprising, results of the unforeseen work-from-home mass experiment: productivity and worker satisfaction are up. And while some companies, particularly financial institutions, are starting to demand that people come in for at least 2-3 days a week, other companies are beginning to accept the reality that they may never be able to force everyone to be in the office regularly. Read more »

Now there is a

Now there is a

“Mankind was first taught to stammer the proposition of equality” – “Everyone is equal to everyone else” – “In a religious context, and only later was it made into morality,” Nietzsche wrote. Elsewhere, he called “human equality,” or “moral equality,” a specifically “Christian concept, no less crazy [than the soul],” moral equality “has passed even more deeply into the tissue of modernity…[it] furnishes the prototype of all theories of equal rights.”

“Mankind was first taught to stammer the proposition of equality” – “Everyone is equal to everyone else” – “In a religious context, and only later was it made into morality,” Nietzsche wrote. Elsewhere, he called “human equality,” or “moral equality,” a specifically “Christian concept, no less crazy [than the soul],” moral equality “has passed even more deeply into the tissue of modernity…[it] furnishes the prototype of all theories of equal rights.”

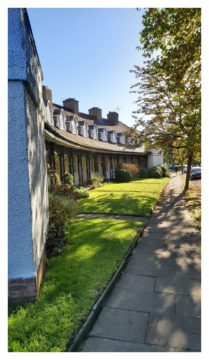

Port Sunlight was a model village constricted in the Wirral, in the Liverpool area, by the Lever brothers, and especially under the inspiration of William Lever, later lord Leverhulme. Their fortune was based on the manufacture of soap, and the village was built next to the factory in the Victorian/Edwardian era, for the employees and their families. It’s certainly a remarkable place, with different houses designed by various architects, parks, allotments, everything an Edwardian working class person might want. An enlightened employer, Lever was still a paternalist: he claimed his village was a an exercise in profit sharing, because “It would not do you much good if you send it down your throats in the form of bottles of whisky, bags of sweets, or fat geese at Christmas. On the other hand, if you leave the money with me, I shall use it to provide for you everything that makes life pleasant – nice houses, comfortable homes, and healthy recreation.” Overseers had the right to visit any house at any time to check for ‘cleanliness’ and that the rules about who could live in which house were observed (men and women could only share accommodation if they were in the same family). Still, by the stands of the day it was quite progressive – schools, art gallery, recreation of all sorts for the employees were important.

Port Sunlight was a model village constricted in the Wirral, in the Liverpool area, by the Lever brothers, and especially under the inspiration of William Lever, later lord Leverhulme. Their fortune was based on the manufacture of soap, and the village was built next to the factory in the Victorian/Edwardian era, for the employees and their families. It’s certainly a remarkable place, with different houses designed by various architects, parks, allotments, everything an Edwardian working class person might want. An enlightened employer, Lever was still a paternalist: he claimed his village was a an exercise in profit sharing, because “It would not do you much good if you send it down your throats in the form of bottles of whisky, bags of sweets, or fat geese at Christmas. On the other hand, if you leave the money with me, I shall use it to provide for you everything that makes life pleasant – nice houses, comfortable homes, and healthy recreation.” Overseers had the right to visit any house at any time to check for ‘cleanliness’ and that the rules about who could live in which house were observed (men and women could only share accommodation if they were in the same family). Still, by the stands of the day it was quite progressive – schools, art gallery, recreation of all sorts for the employees were important.

In 1930, the German anthropologist Berthold Laufer published a monograph on the phenomenon of people eating dirt.

In 1930, the German anthropologist Berthold Laufer published a monograph on the phenomenon of people eating dirt. My grandmother’s bird of choice is the rooster. She was raised in rural Kentucky and now lives in rural Wisconsin. She collects all sorts of roosters (and, by extension, some hens): wall art, printed dish towels, ceramic statues as small as a pinky and as large as a lamp, coin bowls and blankets and something nostalgic in each one.

My grandmother’s bird of choice is the rooster. She was raised in rural Kentucky and now lives in rural Wisconsin. She collects all sorts of roosters (and, by extension, some hens): wall art, printed dish towels, ceramic statues as small as a pinky and as large as a lamp, coin bowls and blankets and something nostalgic in each one.

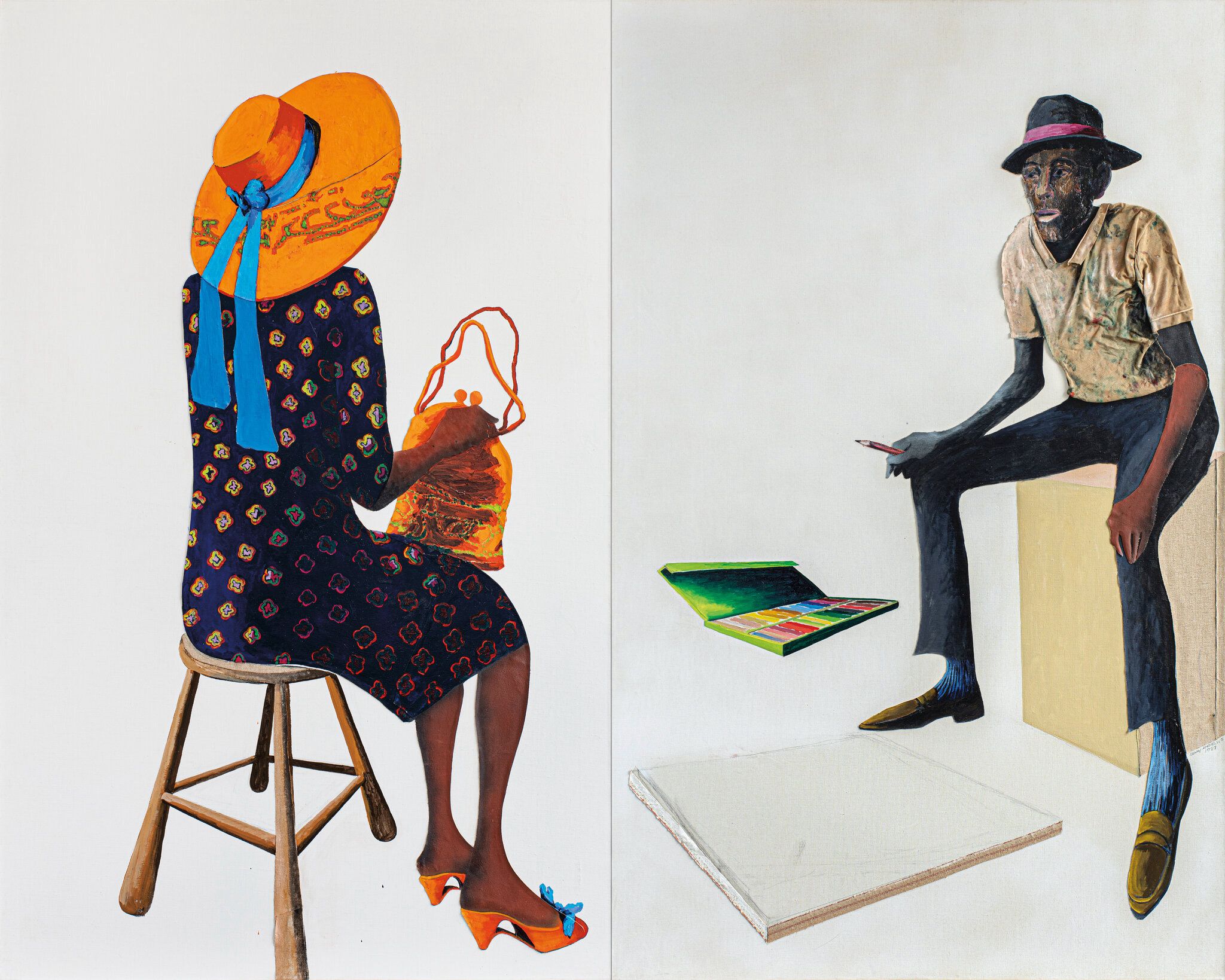

Sughra Raza. Shadow Self-Portrait in a Reflection of a Window in a Window.

Sughra Raza. Shadow Self-Portrait in a Reflection of a Window in a Window.