Narragansett Evening Walk to Base Library

Two young men greeted a new crew member on a ship’s quarterdeck 60 years ago and, in a matter of weeks, by simple challenge, introduced this then 18 year-old who’d never really read a book through to the lives that can be found in them. —Thank you Anthony Gaeta and Edmund Budde for your life-altering input.

bay to my right (my rite of road and sea:

I hold to its shoulder, I sail, I walk the line)

the bay moved as I moved, but in retrograde

as if the way I moved had something to do

with the way the black bay moved, how it tracked,

how it perfectly matched my pace, but

slipping behind, opposed, relative

(Albert would have a formula or two

to spin about this if he were here)

behind too, over shoulder, my steel grey ship at pier,

transfigured in cloud of cool white light,

a spray from lamps on tall poles ashore

and aboard from lamps on mast and yards

among needles of antennae which gleamed

above its raked stack in electric cloud enmeshed

in photon aura, its edges feathered into night,

enveloped as it lay upon the shimmering skin of bay

from here, she’s as still as the thought from which she came:

upheld steel on water arrayed in light, heavy as weight,

sheer as a bubble, line of pier behind etched clean,

keen as a horizon knife

library ahead, behind

a ship at night

the bay to my right (as I said) slid dark

at the confluence of all nights,

the lights of low barracks and high offices

of the base ahead all aimed west, skipped off bay

each of its trillion tribulations jittering at lightspeed

fractured by bay’s breeze-moiled black surface

in splintered sight

ahead the books I aimed to read,

books I’d come to love since Tony & Ed

in the generosity of their own fresh enlightenment

had teamed to bring new tools to this greenhorn’s

stymied brain to spring its self-locked latch

to let some fresh air in crisp as this breeze

blowing ‘cross the bay from where to everywhere,

troubling Narragansett from then

to me here now

Jim Culleny

12/16/19

Carlos Donjuan. Together Alone.

Carlos Donjuan. Together Alone.

A philosopher and a stand-up comedian walk into a bar…the beginning of a joke? Or perhaps a history of humanity from the margins. The philosopher and the stand-up comedian are two figures that keep reappearing across the ages, cutting familiar silhouettes of odd bodies making odd claims about the world and its inhabitants.

A philosopher and a stand-up comedian walk into a bar…the beginning of a joke? Or perhaps a history of humanity from the margins. The philosopher and the stand-up comedian are two figures that keep reappearing across the ages, cutting familiar silhouettes of odd bodies making odd claims about the world and its inhabitants.

First, because Moses, or the prophet Musa as we know him in the Quran, is an unusual hero— a newborn all on his own, swaddled and floating in a papyrus basket on the Nile— my brothers and I couldn’t get enough of his story as children. Second, it is also a story of siblings: his sister keeps an eye on him, walking along the river as the baby drifts in the reeds farther and farther away from home, his brother, the prophet Harun accompanies him through many crucial journeys later in life, another reason the story was relatable. Returning to the narration as a young woman, a mother, I found myself more interested in the heroines in the story: Musa’s birth-mother whose maternal instinct and faith are tested in a time of persecution, the Pharaoh’s wife Asiya who adopts the foundling as her own, confronting her megalomaniac husband’s ire and successfully raising a child of slaves and the prophesied contender to the pharaoh’s power under his own roof. As a diaspora writer, especially one wielding the colonizer’s tongue and negotiating the contradictory gifts of language, I have yet again been drawn to Musa. He is an outsider and an insider— one who carries a “knot on his tongue”— the burden of interpreting and speaking, not entirely out of choice, to radically different entities: God, the Pharaoh and his own people. Among the myriad facets of the legend, the most enduring is the innocence at the heart of his mythos, the exoteric quality of wisdom explored beautifully in mystic writings and poetry as a complementary aspect of the esoteric.

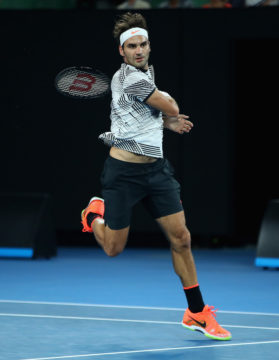

First, because Moses, or the prophet Musa as we know him in the Quran, is an unusual hero— a newborn all on his own, swaddled and floating in a papyrus basket on the Nile— my brothers and I couldn’t get enough of his story as children. Second, it is also a story of siblings: his sister keeps an eye on him, walking along the river as the baby drifts in the reeds farther and farther away from home, his brother, the prophet Harun accompanies him through many crucial journeys later in life, another reason the story was relatable. Returning to the narration as a young woman, a mother, I found myself more interested in the heroines in the story: Musa’s birth-mother whose maternal instinct and faith are tested in a time of persecution, the Pharaoh’s wife Asiya who adopts the foundling as her own, confronting her megalomaniac husband’s ire and successfully raising a child of slaves and the prophesied contender to the pharaoh’s power under his own roof. As a diaspora writer, especially one wielding the colonizer’s tongue and negotiating the contradictory gifts of language, I have yet again been drawn to Musa. He is an outsider and an insider— one who carries a “knot on his tongue”— the burden of interpreting and speaking, not entirely out of choice, to radically different entities: God, the Pharaoh and his own people. Among the myriad facets of the legend, the most enduring is the innocence at the heart of his mythos, the exoteric quality of wisdom explored beautifully in mystic writings and poetry as a complementary aspect of the esoteric. The one regret of my life so far is never having seen Roger Federer play tennis in person. As Federer announced his retirement this year, I’ll never have the chance. The closest I came was the summer of 2017: I was in Italy and planned on flying to Stuttgart to see Federer play in a grass court tournament as preparation for Wimbledon. A few weeks before I was set to leave, I applied for a job at an English language school, largely at the behest of my girlfriend, who was unhappy with the fact that I was “studying” Italian in the mornings and flâning the streets in the afternoons, all while she spent long days toiling away as an unpaid intern in a law office, a common situation in Italy. I didn’t expect to get the job—I had little experience and no real credentials—but I would soon learn that neither of these things mattered, superseded as they were by my being a native speaker. I got the job and had to cancel my trip.

The one regret of my life so far is never having seen Roger Federer play tennis in person. As Federer announced his retirement this year, I’ll never have the chance. The closest I came was the summer of 2017: I was in Italy and planned on flying to Stuttgart to see Federer play in a grass court tournament as preparation for Wimbledon. A few weeks before I was set to leave, I applied for a job at an English language school, largely at the behest of my girlfriend, who was unhappy with the fact that I was “studying” Italian in the mornings and flâning the streets in the afternoons, all while she spent long days toiling away as an unpaid intern in a law office, a common situation in Italy. I didn’t expect to get the job—I had little experience and no real credentials—but I would soon learn that neither of these things mattered, superseded as they were by my being a native speaker. I got the job and had to cancel my trip.

“My account omitted many very serious incidents,” writes Bertrand Roehner, the French historiographer whose analysis on statistics about violence in post-war Japan I used in my Graywolf Nonfiction Prize memoir, Black Glasses Like Clark Kent. He began emailing me at this September about a six-volume, two thousand page report concerning Japanese casualties during the Occupation that has just been released in Japanese after sixty years of suppression.

“My account omitted many very serious incidents,” writes Bertrand Roehner, the French historiographer whose analysis on statistics about violence in post-war Japan I used in my Graywolf Nonfiction Prize memoir, Black Glasses Like Clark Kent. He began emailing me at this September about a six-volume, two thousand page report concerning Japanese casualties during the Occupation that has just been released in Japanese after sixty years of suppression.

I like to vote in person on Election Day. I’m sentimental that way. My polling precinct is at the local elementary school. So last Tuesday, I woke up early, dressed and got out the door in a rush, and arrived to find not the expected pastiche of cardboard candidate signs and nagging pamphleteers, but rather a playground full of 2nd graders.

I like to vote in person on Election Day. I’m sentimental that way. My polling precinct is at the local elementary school. So last Tuesday, I woke up early, dressed and got out the door in a rush, and arrived to find not the expected pastiche of cardboard candidate signs and nagging pamphleteers, but rather a playground full of 2nd graders.

I’m not sold on longtermism myself, but its proponents sure have my sympathy for the eagerness with which its opponents mine their arguments for repugnant conclusions. The basic idea, that we ought to do more for the benefit of future lives than we are doing now, is often seen as either ridiculous or dangerous.

I’m not sold on longtermism myself, but its proponents sure have my sympathy for the eagerness with which its opponents mine their arguments for repugnant conclusions. The basic idea, that we ought to do more for the benefit of future lives than we are doing now, is often seen as either ridiculous or dangerous.