by Muhammad Aurangzeb Ahmad

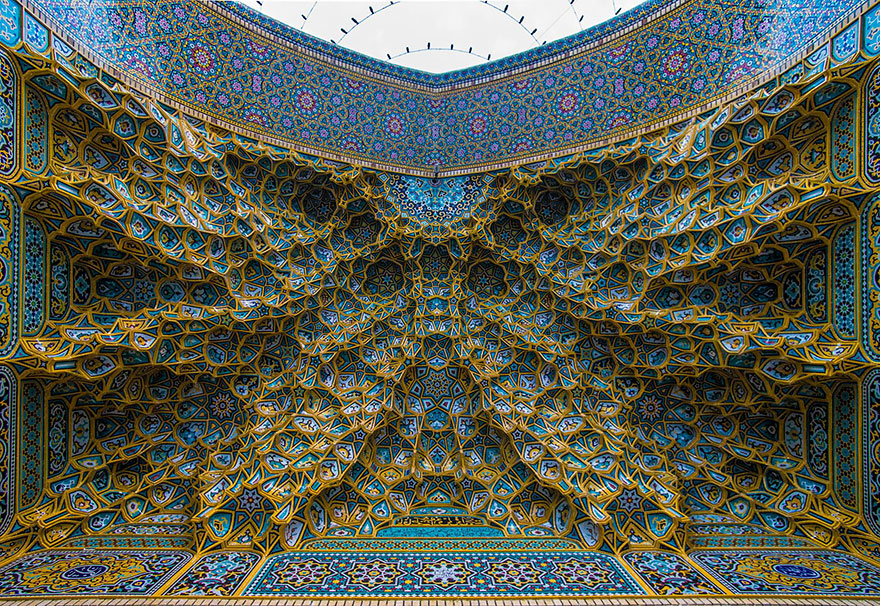

In the last two parts we have discussed encountering the boundary of reason as fracture, and dissolving the boundary altogether. Now we talk about the Islamicate intellectual tradition and how it addresses this threshold. It cultivated a disciplined attentiveness to what appears when knowing falters i.e., a state not of confusion, but of reverent disorientation. In Islamic philosophy and Sufism, the limit of reason is not a catastrophe. It is a disclosure. To reach the boundary of thought is not to exhaust truth. The limit is meant as an opening, it could be outward, inward, upward. Reason could fail but the state of bewilderment that it entails discloses meaning. This orientation reshapes the very role of language, philosophy, and art. No figure articulates this vision more fully than the Spanish Muslim thinker Ibn Arabi. Writing in the thirteenth century, he developed a metaphysics of extraordinary subtlety while insisting, relentlessly, that the Real forever exceeds the structures built to approach it. For Ibn Arabi, reality is not something to be captured but something to be mirrored. The Infinite discloses itself only through finite forms, and those forms are never final. Meaning does not culminate in certainty, it unfolds endlessly through interpretation.

Thus encountering the infinite may lead to paradoxes but they are not meant to be states of failure. Such encounters may even constitute an epistemic virtue! This metaphysics became foundational to Sufism as a lived tradition. Across its many orders and practices e.g., dhikr (remembrance), audition, ethical refinement, disciplined retreat etc the same insight recurs: the self is not annihilated to erase difference, but trained to become permeable. Knowledge is relational. Presence matters more than possession. The limit is not crossed by force, but inhabited with care. In Islamic metaphysics the world is a continuous act of divine self-disclosure (tajalli). Each form is a partial unfolding of an inexhaustible reality. Infinity does not lie beyond the finite; it is enfolded within it. The limit is not where reality ends, but where it becomes legible. Besides Ibn Arabi we see meditations on limits and infinity in the works of thinkers like Suhrawardi’s hierarchies of light to Mulla Ṣadra’s dynamic being, from al-Razi’s interpretive abundance and al-Biruni’s pluralistic cosmology. Read more »

First, because Moses, or the prophet Musa as we know him in the Quran, is an unusual hero— a newborn all on his own, swaddled and floating in a papyrus basket on the Nile— my brothers and I couldn’t get enough of his story as children. Second, it is also a story of siblings: his sister keeps an eye on him, walking along the river as the baby drifts in the reeds farther and farther away from home, his brother, the prophet Harun accompanies him through many crucial journeys later in life, another reason the story was relatable. Returning to the narration as a young woman, a mother, I found myself more interested in the heroines in the story: Musa’s birth-mother whose maternal instinct and faith are tested in a time of persecution, the Pharaoh’s wife Asiya who adopts the foundling as her own, confronting her megalomaniac husband’s ire and successfully raising a child of slaves and the prophesied contender to the pharaoh’s power under his own roof. As a diaspora writer, especially one wielding the colonizer’s tongue and negotiating the contradictory gifts of language, I have yet again been drawn to Musa. He is an outsider and an insider— one who carries a “knot on his tongue”— the burden of interpreting and speaking, not entirely out of choice, to radically different entities: God, the Pharaoh and his own people. Among the myriad facets of the legend, the most enduring is the innocence at the heart of his mythos, the exoteric quality of wisdom explored beautifully in mystic writings and poetry as a complementary aspect of the esoteric.

First, because Moses, or the prophet Musa as we know him in the Quran, is an unusual hero— a newborn all on his own, swaddled and floating in a papyrus basket on the Nile— my brothers and I couldn’t get enough of his story as children. Second, it is also a story of siblings: his sister keeps an eye on him, walking along the river as the baby drifts in the reeds farther and farther away from home, his brother, the prophet Harun accompanies him through many crucial journeys later in life, another reason the story was relatable. Returning to the narration as a young woman, a mother, I found myself more interested in the heroines in the story: Musa’s birth-mother whose maternal instinct and faith are tested in a time of persecution, the Pharaoh’s wife Asiya who adopts the foundling as her own, confronting her megalomaniac husband’s ire and successfully raising a child of slaves and the prophesied contender to the pharaoh’s power under his own roof. As a diaspora writer, especially one wielding the colonizer’s tongue and negotiating the contradictory gifts of language, I have yet again been drawn to Musa. He is an outsider and an insider— one who carries a “knot on his tongue”— the burden of interpreting and speaking, not entirely out of choice, to radically different entities: God, the Pharaoh and his own people. Among the myriad facets of the legend, the most enduring is the innocence at the heart of his mythos, the exoteric quality of wisdom explored beautifully in mystic writings and poetry as a complementary aspect of the esoteric.