by Derek Neal

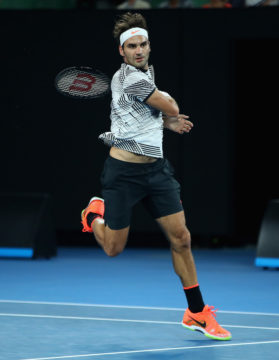

The one regret of my life so far is never having seen Roger Federer play tennis in person. As Federer announced his retirement this year, I’ll never have the chance. The closest I came was the summer of 2017: I was in Italy and planned on flying to Stuttgart to see Federer play in a grass court tournament as preparation for Wimbledon. A few weeks before I was set to leave, I applied for a job at an English language school, largely at the behest of my girlfriend, who was unhappy with the fact that I was “studying” Italian in the mornings and flâning the streets in the afternoons, all while she spent long days toiling away as an unpaid intern in a law office, a common situation in Italy. I didn’t expect to get the job—I had little experience and no real credentials—but I would soon learn that neither of these things mattered, superseded as they were by my being a native speaker. I got the job and had to cancel my trip.

The one regret of my life so far is never having seen Roger Federer play tennis in person. As Federer announced his retirement this year, I’ll never have the chance. The closest I came was the summer of 2017: I was in Italy and planned on flying to Stuttgart to see Federer play in a grass court tournament as preparation for Wimbledon. A few weeks before I was set to leave, I applied for a job at an English language school, largely at the behest of my girlfriend, who was unhappy with the fact that I was “studying” Italian in the mornings and flâning the streets in the afternoons, all while she spent long days toiling away as an unpaid intern in a law office, a common situation in Italy. I didn’t expect to get the job—I had little experience and no real credentials—but I would soon learn that neither of these things mattered, superseded as they were by my being a native speaker. I got the job and had to cancel my trip.

For readers who are not fans of Federer, my above statement may seem hyperbolic, but I am writing in earnest. Sports, and specifically tennis, being an individual sport, have the ability to become representative of something larger than themselves. In tennis, the great players embody a way of life through their playing styles. Federer, being the most graceful and beautiful player, makes us think that one can live a life in this way, moving through the world in harmony with our surroundings, never forcing one’s desires but letting their fulfillment come to us, and acting in accordance with what might be called the laws of nature. This is how Federer moves around the tennis court. At his best, he seems to be a Zen sage who has attained enlightenment. Rafael Nadal is the foil to Federer’s grace. Nadal shows us that anything can be achieved through hard work and perseverance. He plays with force and power, grunting as he hits the ball, bending the world to his will and conquering all that lays before him. Fans of Nadal, I imagine, have this worldview and admire him for its representation in his style of play. Read more »

“My account omitted many very serious incidents,” writes Bertrand Roehner, the French historiographer whose analysis on statistics about violence in post-war Japan I used in my Graywolf Nonfiction Prize memoir, Black Glasses Like Clark Kent. He began emailing me at this September about a six-volume, two thousand page report concerning Japanese casualties during the Occupation that has just been released in Japanese after sixty years of suppression.

“My account omitted many very serious incidents,” writes Bertrand Roehner, the French historiographer whose analysis on statistics about violence in post-war Japan I used in my Graywolf Nonfiction Prize memoir, Black Glasses Like Clark Kent. He began emailing me at this September about a six-volume, two thousand page report concerning Japanese casualties during the Occupation that has just been released in Japanese after sixty years of suppression.

I like to vote in person on Election Day. I’m sentimental that way. My polling precinct is at the local elementary school. So last Tuesday, I woke up early, dressed and got out the door in a rush, and arrived to find not the expected pastiche of cardboard candidate signs and nagging pamphleteers, but rather a playground full of 2nd graders.

I like to vote in person on Election Day. I’m sentimental that way. My polling precinct is at the local elementary school. So last Tuesday, I woke up early, dressed and got out the door in a rush, and arrived to find not the expected pastiche of cardboard candidate signs and nagging pamphleteers, but rather a playground full of 2nd graders.

I’m not sold on longtermism myself, but its proponents sure have my sympathy for the eagerness with which its opponents mine their arguments for repugnant conclusions. The basic idea, that we ought to do more for the benefit of future lives than we are doing now, is often seen as either ridiculous or dangerous.

I’m not sold on longtermism myself, but its proponents sure have my sympathy for the eagerness with which its opponents mine their arguments for repugnant conclusions. The basic idea, that we ought to do more for the benefit of future lives than we are doing now, is often seen as either ridiculous or dangerous. Sughra Raza. Valparaiso Expressions. Chile, November 2017.

Sughra Raza. Valparaiso Expressions. Chile, November 2017.

Climate change and covid are revealing an ongoing inability for our society to make wise decisions in the face of calamity, which may be leading us to a collapse of our civilization. Perhaps if we accept (or just believe) that we’re nearing the end, we can shift our priorities enough to usher in a more peaceful and equitable denouement.

Climate change and covid are revealing an ongoing inability for our society to make wise decisions in the face of calamity, which may be leading us to a collapse of our civilization. Perhaps if we accept (or just believe) that we’re nearing the end, we can shift our priorities enough to usher in a more peaceful and equitable denouement.