by Dwight Furrow

If we are to believe the most prominent of the writers we now lump under the category of “existentialism,” human suffering in the modern world is rooted in nihilism. But I wonder whether this is the best lens through which to view human suffering.

If we are to believe the most prominent of the writers we now lump under the category of “existentialism,” human suffering in the modern world is rooted in nihilism. But I wonder whether this is the best lens through which to view human suffering.

According to existentialism, as the role of God in modern life receded to be replaced by a secular, scientifically-informed view of reality, the resulting loss of a transcendent moral framework has left us bereft of moral guidance leading to anxiety and anguish. The smallness of human concerns in a vast, uncaring universe engenders a sense that life is inherently meaningless and absurd. There seems to be no ultimate purpose in life. Thus, our individual intentions are without foundation.

As Camus wrote:

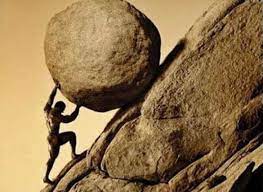

The absurd is born in this confrontation between the human need and the unreasonable silence of the world. (From the Myth of Sisyphus)

And so, for Camus, human suffering is like the toils of Sisyphus condemned to endlessly roll the boulder up the mountain only to have it roll down again—life is a series of meaningless tasks and then you die.

Sartre, for his part, argued that the demise of a theistic world view means we must now confront the incontrovertible fact of human freedom—no state of affairs can cause us to act in one way rather than another. Furthermore, there are no values that have a claim on us prior to our choosing them. Instead, at each moment, we make a choice about the significance of facts and our relation to them. If life is to be meaningful, we must invent that meaning for ourselves. We are thus “condemned” to be free and must take full responsibility for our actions and the meaning we attribute to them. Read more »

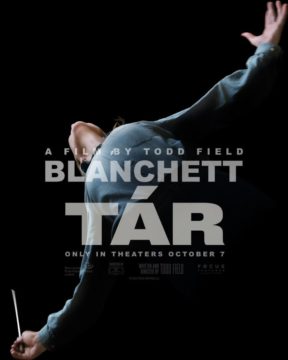

Blanchett’s performance has been much praised, and it is indeed a tremendous thing: she must be near the head of the queue for an Oscar this year. It’s a great performance in a genuinely worthwhile and absorbing film. I don’t think it really expands our understanding of the themes it features: power and the exploitation young hopefuls by the (seemingly) all powerful star, the question of great art and flawed artists and so on, but it’s possible to come out of the movie thinking that it has. Blanchett’s performance has a lot to do with that. So a great performance in a very good rather than great film (assuming such categories can really be employed so neatly).

Blanchett’s performance has been much praised, and it is indeed a tremendous thing: she must be near the head of the queue for an Oscar this year. It’s a great performance in a genuinely worthwhile and absorbing film. I don’t think it really expands our understanding of the themes it features: power and the exploitation young hopefuls by the (seemingly) all powerful star, the question of great art and flawed artists and so on, but it’s possible to come out of the movie thinking that it has. Blanchett’s performance has a lot to do with that. So a great performance in a very good rather than great film (assuming such categories can really be employed so neatly).

In

In  For the last several years, elected Republicans, full of anti-trans zeal, have challenged their opponents to define the word “woman.” They aren’t really curious. They’re setting a rhetorical trap. They’re taking a word that seems to have a simple meaning, because the majority of people who identify as women resemble each other in some ways, then refusing to consider any of the people who don’t.

For the last several years, elected Republicans, full of anti-trans zeal, have challenged their opponents to define the word “woman.” They aren’t really curious. They’re setting a rhetorical trap. They’re taking a word that seems to have a simple meaning, because the majority of people who identify as women resemble each other in some ways, then refusing to consider any of the people who don’t.

Let’s get the humble-bragging out of the way first: I’ve always had a remarkable memory.

Let’s get the humble-bragging out of the way first: I’ve always had a remarkable memory.