by Mark Harvey

If you submitted yourself to the idiotic torture over last week’s battle to elect the speaker of the house for the 118th Congress, then you deserve a break from that idiocy and the chance to think about something else. American politics at the national level make toxic uranium dumps seem like tea gardens. The petulance and pettiness of many of our politicians make daycare centers seem like bastions of diplomatic protocol.

But there are things to think about in this great land that are a salve and rampart against the most cretinous of our congresspersons: the many efforts of Americans to steward lands back to health.

Let’s not mince words: in a few hundred years on this continent, we have trashed millions of acres and imperiled thousands of species. From Seattle to Tampa, from Galveston to Fargo, and even in parts of Alaska, what we’re facing is the aftermath of a resource-eating orgy. Now we face the unpleasant hangover and picking up all the broken bottles. But some Americans with pluck, eternal optimism, can-do, and deep allegiance to the land are doing it.

Let’s start with beavers. For millions of years, the chunky beaver with its webbed feet, buck teeth from hell, oily fur, and skillet tail ruled American wetlands and rivers. With their a priori instincts to build dams strategically (refer back to your Immanuel Kant), they created thousands of ponds and wetlands on thousands of streams. Call them wetland engineers or riparian geniuses, their thousands of dams served as settling ponds to clean streams and rivers, provide habitat for fish, waterfowl, and songbirds, and retain water upland instead of seeing it just rip down the valleys. Even their lodges provided great habitat for swans who used them for nesting sites.

In the Rocky Mountain West, where most of the annual water comes in a few short months when the snow melts, beaver dams regulate the downstream flow. Studies show that beaver dams retain 30-60% of streamflow and then gradually release that water as the snow runoff tapers. The effect is to better distribute available water through the drier months rather than just having it race down the valleys at peak runoff.

Beaver dams also recharge groundwater and raise aquifers. In communities dependent on well water, this effect is crucial.

The standing water resulting from beaver dams serves as remarkable settling ponds. In its ten-year lifespan, a beaver pond retains an average of 85,000 cubic feet of sediment. The result is reduced turbidity downstream, making life easier for fish and riparian plants.

Beaver ponds and the resulting wetlands increase plant and wildlife diversity radically. One study suggests that beaver ponds increase bird populations by as much as 300%. Other plants and animals benefiting include boreal toads, trout, amphibians, herbaceous plants, and invertebrates.

What almost wiped out the American beaver population was a fashion trend that began around 1550 and lasted close to 300 years—beaver hats. Hatters discovered that beaver pelts made for superior felt and hats that were envied and in high demand. The great American fur trade began with the French in what is now eastern Canada and quickly spread west all the way to the Rockies. The first Europeans to really explore the Rockies were fur trappers in search of beaver pelts. In just a few decades, the trappers nearly wiped out the beavers and the landscape changed radically.

It’s estimated that there were hundreds of millions of beavers in the United States before the heavy beaver trapping began. And consequently, the American landscape used to have far more wetlands. Wetlands are crucial to biodiversity and support wildlife and plants far beyond their geographical footprint. For instance, in the west today, wetlands account for only about two percent of the land mass but sustain roughly 80 percent of its biodiversity. Even early Americans of the 19th century inherited a land heavily degraded by the near extinction of beavers.

But the story of the beaver’s comeback is heartening and impressive. Throughout the United States, private and public parties are doing all kinds of interesting things to bring back our chubby water engineers.

If you haven’t read Ben Goldfarb’s book Eager: The Surprising Life of Beavers and Why They Matter, and are interested in beavers, it’s a great book and very compelling. In it, he describes some early attempts to restore beavers to Idaho by its fish and game department in the late 1940s. The state government first tried to pack the beavers into the mountains by horse. As you can imagine, the horses didn’t like it at all. As Elmo Heter, the state biologist in charge of the operation put it, “Horses and mules become spooky and quarrelsome when loaded with a struggling, odorous pair of live beavers.”

Goldfarb goes on to describe the ingenious way the Idaho state government eventually got beavers into the backcountry: by parachute. It took a lot of experiments to find a way to safely parachute beavers into the backcountry. The first idea was to build willow baskets that the beavers could gnaw their way out of once on the ground. But Heter realized the beavers might gnaw their way out while still in the plane, which could end in a disaster. So he came up with a different solution. Goldfarb writes,

With willow out, the persistent Heter invented a different package—a suitcase-like crate whose elastic straps fell open upon impact. The onus of serving as crash-test pilot fell first to an old male beaver named Geronimo. Officers repeatedly pitched Geronimo’s crate onto a landing field, trials that Heter relayed with a decidedly unscientific tone. “Each time he scrambled out of the box, someone was on hand to pick him up. Poor fellow! He finally became resigned, and as soon as we approached him, would crawl back into his box ready to go aloft again.”

The aerial relocation of beavers in the fall of 1948 was an unqualified success. Of the 76 beavers dropped from the plane, only one died. The beavers that landed safely quickly colonized the area and brought back wetlands.

When beaver hats were in great demand, the great fur trading companies resorted to extreme measures to outcompete their rivals. The Hudson Bay Company, one of the largest fur companies, took the fight to what is today Oregon when it was competing with American trappers near the Columbia River. Under George Simpson, then president of the business, the Hudson Bay Company began its “fur desert” campaign. Hudson Bay trappers sought to eliminate all desirable fur-bearing animals on numerous waterways just to deter their American competition from operating in the same region. It was an eerie parallel to the American government’s attempt to wipe out the buffalo just to eradicate Indians.

Since Heter’s heroic Normandy-like reintroduction of beavers to Idaho, lots of other enterprises have succeeded as well. On the Zuni Nation, which spans 60,000 acres in Arizona and New Mexico, Zuni Indians have been working with beaver restoration since at least the 1980s. Historical literature written by early explorers suggests that the southwest once had extensive beaver populations and wetlands.

In a 2000 issue of Ecological Restoration, Steven Albert and Timothy Trimble describe efforts by the Zuni Fish and Wildlife Department to restore wetlands and riparian areas with beavers. By relocating beavers from thriving colonies to areas with some running water and potential food sources (mostly willows), the department successfully improved previously degraded habitat. Within weeks of being introduced, the beavers built dams, increasing surface and subsurface water. The habitat improved and Albert and Trimble noticed more birds in the area, especially willow flycatchers. Another marked improvement was the reduction of salt cedar (tamarisk), an aggressive and problematic non-native species plaguing much of the southwest. Apparently the salt cedar doesn’t like the repeated flooding caused by the beaver dams.

On a larger scale, certain National Forests have begun to incorporate beaver restoration plans. Under a recent update in forest planning policy, what’s called the 2012 Planning Rule, requires National Forests to “….maintain or restore the ecological integrity of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems…including plan components to maintain or restore structure, function, composition, and connectivity.” The rule goes on to include “…plan components, including standards or guidelines, to maintain or restore the diversity of ecosystems and habitat types throughout the plan area.”

If ever there was a national policy that begged for restoring beaver populations, it is this 2012 Planning Rule. National Forests such as the Custer-Gallatin, the Rio Grande, and the Okanagan-Wenatchee have already begun to incorporate beaver restoration into their plans.

The National Marine Fisheries Service has also incorporated beavers in their plans to save salmon fisheries in Oregon after studies showed that two-thirds of Oregon’s coastal Coho spend their winter months in ponds and slack waters resulting from beaver ponds.

My mention of a priori dam-building knowledge and Immanuel Kant above is obscure but worth considering. For beavers seem to have the dam-building instinct wired into their brains. There’s a very cute video of an orphan beaver living with a woman who runs a small rescue center. The baby beaver builds dams throughout the house and uses everything available (shoes, bins, stuffed animals, door mats) to build its dam. One has to assume it’s hard-wired into their brains.

In a time when our national politics are just loathsome, it’s good to think about the lives and futures of the wild creatures more noble and aspiring than some of our congresspeople. Take skunks for example. I see far more redeeming value in the life of a spotted skunk than in some of the grotesque posturing and dissembling of many of our politicians. What really stinks is the blind ambition of some in Washington DC, not the musk of our spotted friend. While the skunk can spray some pretty rank chemicals, it also does a lot of good eating insects and small rodents that might otherwise overpopulate. To my knowledge, a skunk has never written a stupid virtue-signaling bill or made a vapid speech that insults its constituents.

A 2005 study suggests that the population of the Eastern Spotted Skunk has declined by more than 95% over the last 60 years, most likely due to habitat loss. In some states, the eastern spotted skunk is endangered. Throughout most of North America its status is categorized as “vulnerable.”

I find it somehow comforting to know that a collection of very good scientists and universities are endeavoring to better understand this pungent critter with hopes of preventing its total demise. Easy to throw in behind the more charismatic animals like the bald eagle or the grizzly bear, but to study and champion skunks truly speaks of a commitment to the underdog and restoration of the land. Up until this morning, I didn’t know of the existence of The Eastern Spotted Skunk Cooperative Study Group (ESSCSG). I didn’t know that the ESSCSG consisted of 68 members representing 16 universities, 5 federal agencies, and 15 state agencies. I didn’t know the depths to which this group has gone to figure out how the spotted skunk lives, what it eats, how it reproduces, and what is leading to its precipitous decline.

In a 45-page report, dense with information, the ESSCSG discusses everything from the mitochondrial DNA of the skunks to pathogens threatening their health. The thought of good American scientists doing unheralded but important research that may help bring back some balance to our ecology stirs far more patriotic sentiment in my soul than the parading of giant flags in jacked-up pickup trucks.

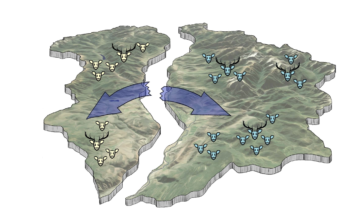

In the valley where I live, a couple of friends are doing a restoration project that could well be consequential for this part of western Colorado. Tom Cardamone, founder and executive director of the Watershed Biodiversity Initiative, worked with Colorado State University to study and map the habitat and biodiversity of the one-million-acre watershed surrounding the Roaring Fork River. The study revealed the most critical habitat for elk, mule deer and bighorn sheep in the watershed as well as sections where the habitat is most fragmented by highways. Every year, Colorado Highway 82, which links Glenwood Springs to Aspen, sees dozens of elk and deer killed from the heavy volume of traffic. It’s not just elk and deer but also bears, raccoons, coyotes, and rodents. Another local, Cecily DeAngelo, is using that information in her newly formed group Roaring Fork Safe Passages to one day build structures that will allow wildlife to cross the deadly Colorado Highway 82 without getting killed.

The work that DeAngelo and Cardamone are doing is partly modeled on successful crossings built in places like the Canadian province of Alberta, Nevada, and Europe. It will take time, energy, money, and planning, but I suspect in the next five to ten years, our watershed will be much more intact with these planned crossings.

We really do need things to raise our spirits in this age of willful ignorance, big wars, insipid politicians, and a failing climate. Might I suggest getting involved in ecological restoration wherever you live. The great movement of “citizen scientists” across the country allows people of every age and every background to get involved in real, effective, and meaningful studies and restoration efforts. This short article from a 2018 issue of Yale Environment Review describes how thousands of students became citizen scientists in Portland, Oregon, in a study of two creeks. Over seven years, the students collected and identified more than 14,000 macroinvertebrates. The hope is that the studies lead to effective restoration. There are thousands of opportunities across the country for this sort of thing and the work is almost always deeply rewarding.

If I were a college student, I would seriously consider studying some form of ecological restoration. We will need great minds and youthful energy for generations to come if we are to recover a semblance of what this nation once had. And a career in the outdoors helping critters like the ungainly but industrious beaver or the eastern spotted skunk would sure beat the many suffocating vocations offered by our modern economy.