by Carol A Westbrook

“Describe your family” was the assignment in my high school sociology class. A straightforward exercise, it was meant to show us how families are the basis on which all the other social institutions are modeled.

It was 1966. I lived in a tidy little bungalow with Mom and Dad, my sister and my two brothers. All four grandparents, deceased at the time, were Polish Catholic immigrants, which explains why my father had 11 siblings, while my mother had 4! Most of these uncles and aunts were married with large families of their own, so I had about 50 first cousins. All of these relatives lived nearby, in the Chicago area. I knew every one of them. This was my family.

At the time of the assignment, most families were “traditional.” Mother, father, siblings, uncles, aunts. There were no gay marriages then, with two mothers or two fathers, and there were few “blended” families of divorce. Furthermore, most adopted children didn’t know their birth parents, and thus did not include them in their families. Today things have changed, but families still remain as the basic social unit.

T hat being said I had a few “lost” relatives. Uncle C, the youngest on my mother’s side, married Aunt R, and had 4 children. I was even the flower girl at their wedding! Uncle C walked out on her—as they did in those days—leaving his wife and kids to fend for themselves. Mom said if he ever showed up, or if they found him, she wouldn’t ever speak to him again! He was kicked out of the family, and we lost contact with Aunt R and the kids. [He was later found and sued for divorce and child support, which he paid]. He went out West.

hat being said I had a few “lost” relatives. Uncle C, the youngest on my mother’s side, married Aunt R, and had 4 children. I was even the flower girl at their wedding! Uncle C walked out on her—as they did in those days—leaving his wife and kids to fend for themselves. Mom said if he ever showed up, or if they found him, she wouldn’t ever speak to him again! He was kicked out of the family, and we lost contact with Aunt R and the kids. [He was later found and sued for divorce and child support, which he paid]. He went out West.

Cousin R, about my age, ran away from home, but eventually got in touch with his parents. He had moved to the West Coast, now with a wife and children. Next was Aunt C, the oldest aunt, who left Chicago during the depression to move West, to make her fortune. She tried a few money-making ventures, including a chicken farm! Now married and divorced, she never made a fortune, but came back came back to visit twice, and that’s when I met her. Children? Don’t know. She was found dead of a stroke, in a rented room, alone.

Uncle J, Dad’s oldest brother, had a colorful past. He rode the rails during depression times, doing odd jobs, and joined the Army at age 15. When World War 2 started, he went AWOL from the Army in order to join the Navy, at which time he saw action as a First Gunner’s Mate. Family lore has it that he married and had 2 daughters, whom he left behind on the West Coast. He returned to Chicago, where he lived (at the time) with his brother and mother on his military pension until he died. He never talked about his past.

You can see why I call these “lost” relatives. Family lore has it that they all moved to the West Coast, but perhaps that’s just our creative imagination—where would we go if we had to leave? What if that big earthquake finally hit, and all my West-Coast relatives moved back to Chicago. Would they be Family? No, they would still be relatives, of course, but definitely not Family. The difference between Family and distant relatives is easy for me to understand, but hard to explain. I know and trust the members of my Family, but I don’t feel that way about relatives whom I have only met briefly.

On the left is a photo taken at our “Cousin’s Reunion,” in 2017. This is a get-together of all 21 (minus  3) of my first degree cousins on my father’s side, and their spouses. I know all of them well, having grown up alongside them, though many I hadn’t seen for over 20 years—and those 20 years might well have been yesterday! I look at this photo and I think “I love you guys!”

3) of my first degree cousins on my father’s side, and their spouses. I know all of them well, having grown up alongside them, though many I hadn’t seen for over 20 years—and those 20 years might well have been yesterday! I look at this photo and I think “I love you guys!”

Not everyone is so lucky as to be blessed with so many relatives to love. People such as orphans, people sired by sperm donors, and people whose real father is not the guy on their birth certificate may not know their relatives at all. For them, there is DNA testing. Many people have submitted samples of DNA to services such as Ancestry.com and 23AndMe to find relatives. DNA testing has opened up a new dimension to family connections, as it can draw family trees and find even distant relatives, giving truth to the adage that we are all related by six degrees of separation.

A striking example of the use of a database to find a DNA match is the story of the capture of the notorious “Golden State Killer.” This criminal committed serial rapes and murders across California in the 1970s and 1980s. The killer’s DNA found no matches in existing DNA databases, but a service called GEDMatch was used to construct a family tree from the killer’s DNA. GEDMatch contains  sequences of 350 million people from six DNA matching services, as well as sophisticated genealogy software. It was used to construct a family tree for the criminal and identify 20 likely relatives. By investigating these 20 relatives, a team of detectives narrowed in on D’Angelo who was shown to be involved in at least 13 murders and more than 50 rapes. He was arrested and convicted in 2018. Quickly thereafter, genetic testing of murder and rape evidence solved almost 50 other crimes! This type of analysis only works if the suspect’s relatives have submitted their DNA to a public ancestry database—in other words if they are white and live in the United States. If so, there’s a good chance an internet sleuth can identify the suspect from a DNA sample he left somewhere.

sequences of 350 million people from six DNA matching services, as well as sophisticated genealogy software. It was used to construct a family tree for the criminal and identify 20 likely relatives. By investigating these 20 relatives, a team of detectives narrowed in on D’Angelo who was shown to be involved in at least 13 murders and more than 50 rapes. He was arrested and convicted in 2018. Quickly thereafter, genetic testing of murder and rape evidence solved almost 50 other crimes! This type of analysis only works if the suspect’s relatives have submitted their DNA to a public ancestry database—in other words if they are white and live in the United States. If so, there’s a good chance an internet sleuth can identify the suspect from a DNA sample he left somewhere.

DNA testing is a powerful tool. It can diagnose a rare childhood metabolic disease which can be treated with diet but is otherwise fatal. Or it may disrupt a family by revealing non-paternity or even non-maternity. Anyone who submits their DNA for analysis may find they are carrying a gene for cancer, or for a fatal disease, such as Lou Gehrig’s disease (ALS), Polycystic kidney disease (PKD), or any other of a number of incurable diseases that strike older people. It’s important for a person to consider in advance what they would do if their DNA had one of these surprises. Nonetheless, people want to know.

The drive to be part of a family is powerful. It has been in our genes even before humans evolved as a species. Humans and related primates are the only animal species in which both parents live together and share the responsibility for raising the children, and in which the children still know their parent

s after the first year of life. By contrast, most social animals live in packs or herds and have never met their parents. Fewer still are raised by both biologic parents in the company of their siblings. Most animals either live alone or spend their days with half-siblings, uncles, cousins many times removed or a herd or flock of genetic strangers.

Families have a crucial role in social development. They bear the primary responsibility for the education and socialization of children as well as instilling values of citizenship It is the first institution where young children are acculturated. It is through family that everyone learns their values and where people first get a sense of belonging and of love. It makes us human.

So what will the family be like in 2050? Will we still have nuclear families, with a heterosexual couple raising their children in a home, zipping around in their flying drone cars, as depicted by the Jetsons some 50 years ago? For millennia, the family has followed this norm. It is reinforced by law, by religion and by social acceptance. But it is clear that this model of family is changing. Factors impacting this change in family structure include the sexual revolution; the easy access to birth control, abortion and divorce; the acceptance of sexual and racial diversity; and the acceptance of child-bearing outside of wedlock

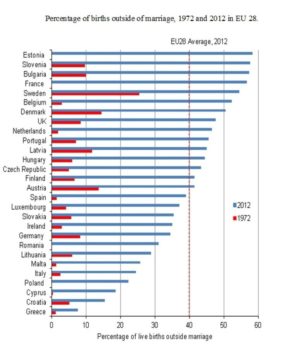

A study of European families by the World Economic Forum has found that that from the early 1970s, marriage and childbearing began to be postponed and cohabitation and non-marital childbearing started to increase, as can be seen in the chart on the right.

There has been a movement toward new family forms including same-sex and LGBTQ families, one parenthood, childless unions and cohabiting couples. Better health and longevity means that will have more grandparents than children. The role that genetic engineering will play cannot even be fathomed. The future family may not resemble the Jetsons. It is imperative that the government, churches and other important social institutions recognize and sanction these families, in order to ensure a healthy and well-adjusted group of children in the next generation.