by Mike Bendzela

And on the pedestal, these words appear: . . . “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!” Nothing beside remains. —From “Ozymandias,” Percy Bysshe Shelley

Prologue from Part One

An investigation into the livelihoods of two great-great grandfathers, both oilfield workers in Ohio, has of necessity become a study in the nature of forgetting.

I have sought one thing–my ancestral grandfathers’ involvement in the history of oil production in Northwest Ohio–only to have it slip through my fingers. In the process I have found something else, a great grandmother both besotted and besieged by the men in her life, someone whom I can scarcely look away from. With the help of my brother’s research and my mother’s endless stories, I will try to draw Grandma Blanche’s tale out of the dust of an extinct oil town.

*

Part Two: The Oil Pumper’s Daughter

After my failure to find any remnants of my great, great grandfathers’ involvement in Northwest Ohio’s oil industry, I had only my great-grandmother Blanche left to talk about. I have just a few census documents and a clutch of my mother’s anecdotes. But what documents, what anecdotes!

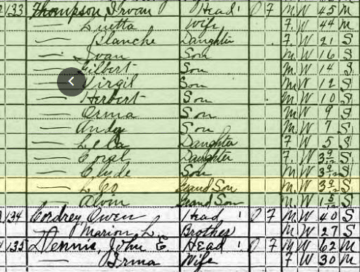

The left half of that 1920 Federal Census document I reproduced in Part One deserves another look, as it contains several clues about the family history as told by my mother, clues with hair-raising implications:

One immediately notices that the oil pumper, Irvan, and his wife, Luetta, had 12 children under their tiny roof in 1920, including Blanche, my great grandmother, the eldest at 21. One also notices that Luetta was caring for twins at the time, Coral and Clyde, and that, at 3 years, 9 months of age, they had to have been born around the time she turned 40. The eldest grandson, Leo, was also 3 years and 9 months old (highlighted in yellow). That’s Blanche’s first child, my grandfather. That means mother and daughter were pregnant at the same time, and they gave birth to their children during the same month. The nephew was the same age as his aunt and uncle, and he would grow up with the same last name as theirs, as would his half-brother, Alvin, shown here as age 1 year, 5 months. Patrimony of both, unknown.

That Leo and his brother had their mother’s maiden name was a stigma they carried around for life. At Leo’s funeral 1969, Alvin was asked by someone in attendance, quite innocently, how he had come to have the same last name as his mother.

“That has haunted me my whole life,” he said.

At that funeral for her father, my mother recalls there being a nun, (probably a friend of my mother’s sister, who was in a convent at the time), who looked around the room and said, “This is the saddest funeral I have ever been to.”

“What do you mean?” my mother asked. “No one’s crying here.”

“That’s what I’m talking about,” the nun said.

That is the summation of the poor bastard’s whole life.

*

It’s unclear whether my mother’s half uncle Alvin ever learned the truth about his patrimony. He married a good woman, whom my mother kept in touch with. It was the aunt’s testimony that became the sole link my mother had to the secret of her father’s origins, and that is merely anecdotal. This aunt once told my mother during a phone call, “The rumor is, your grandfather was John Dennis. Just be lucky you’re not a S________ .”

We had always called Grandma Blanche “Grandma S________,” the last name of the man she eventually settled down with and married when my grandfather was still a child. Scandal would follow her right into married life. As the descendants of their family are still around, and as I do not have their permission to air their dirty laundry, S________ will have to do.

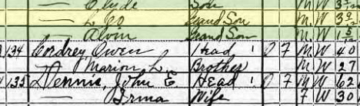

There was no way to confirm the truth of what Mom’s aunt told her, but there is a tantalizing hint: The final shock of that 1920 Census document is what appears directly below the list of the family residing at the dilapidated Dowling Road address, which, from what I remember as a kid, lay within spitting distance of the other dwellings in the settlement. Two addresses away, the census-taker would write down, in beautiful script:

Some calculations are in order. Blanche was born in July of 1898. Leo was born in March of 1916. Counting backwards the approximate number of days (280) for the gestation of a human fetus, we come to a date of conception in June of 1915–when Blanche was still 16 years old.

According to the census, when Leo was 3 years, 9 months old, John Dennis was 62. That means he would have been about 58 when Leo was conceived. I can’t imagine Irvan and Luetta countenancing such a relationship between their teenaged daughter and the carpenter three times her age who lived nearby with a wife half his age (Irma, 30). There is also record of the guy having had multiple wives and at least three families.

There is another problem: John Dennis’s son from his first wife was also named John, born 1889. So, while a DNA test has revealed that I am directly related to these Dennises, (my sister and I both share substantial percentages of our genes with the Dennis clan), there is no way to pin down the actual father–the old man or the son. Certainly, one of them was my grandfather’s clandestine father.

That Grandma Blanche had another illegitimate son a couple of years later suggested to my mother that she was a “free spirit.” She added, “Though they didn’t really have a word for it at the time.”

My mother recalls having a school project as a girl of eight, wherein the teacher asked students to design a family tree, depicting the branching of ancestors as far back as they could go. Mother brought the chart home for her mother to help fill out. Mom’s maternal side of the chart was easy to fill out. But what about Leo’s side?

“Who was dad’s dad?” my mother asked.

“I don’t know,” her mother told her.

About this incident, my mother told me on the phone, “Well, I said to myself, I’m not turning that in!” And she threw the assignment away. How horrible to have to feel ashamed of something that is in no way your own fault.

I asked her why she didn’t just ask her father who her grandfather was.

“He was never around,” she told me. “Or he was recovering from a hangover.”

Leo turned out to be a bastard in more ways than one. Those wild-ass genes from Grandma Blanche, free spirit, and from one or the other John Dennis had come together to create a monster: a womanizer, a drunkard, a brute. But a charmer, according to Mom. He had won over my decently Catholic grandmother (granddaughter of yet another Ohio oil pumper), in spite of his cruelties. A chip, perhaps, off the old block.

Mother’s memories of him are universally awful. There were frequent break-ups, and afterwards he would try to get into the house to see his estranged wife. He had been caught by my grandmother visiting with another woman, and when he broke in one night, ranting and drunk, my mother screamed at him, “Why don’t you go back to your girlfriend!” For this, for other ways of expressing her outrage, she was humiliated, belittled, even punched.

But Mother always loved her mean dad’s mother, Blanche, no matter how eccentric she turned out to be. Mother has described for me a lasting image of Blanche being dropped off at the house to visit her grandchildren when Mom’s parents were still married. After her husband died, Blanche had a live-in “handy man,” a trucker of gravel, named Melvin, whom her second son Alvin just hated. It was Melvin who would deliver her to the house for visits. He would stop his dump truck out in front of the little residence in East Toledo where my mother lived with her mother and siblings; Blanche would shoulder open the door; and as she climbed down out of the passenger side of the truck, her skirt rode up, revealing rolled-down nylon stockings held in place by black straps and garter clips.

Mom and I just howl together at the image.

*

They actually did have a word back then for free spirits like Blanche. Here in Maine it’s pronounced something like “hoo-wah.” But that’s grotesque, unfair, and cruel. I’ll bet no one ever called John Dennis (nor his son) a whore, and I’ll bet no one ever called the father of Leo’s half-brother Alvin a whore, nor that live-in “handy man,” Melvin, nor any of the other men who took advantage of their poor, female neighbors. Let free spirits be free–except, apparently, women who find themselves stranded in defunct oil towns in Ohio.

One of mother’s earliest memories of Grandma was of visiting her at the Dowling family home and seeing her walking along the railroad tracks, picking dandelions for her wine. That’s where she picked the blackberries and elderberries for her purple jams as well. Those tracks cut across Dowling Road at a harsh angle, as if they didn’t care where they were running those tracks when they put them there in the 19th century. The settlement was a self-contained little shithole, but those of us who didn’t know any better–me; my mother as a child–thought it magical. Mother remembers peeking into the windows of the chicken hatchery next door and seeing all the little birds inside. She envied the people who tended to the chicks, as they got to live in the back room of the hatchery–a whole family–and they had orange crates for furniture!

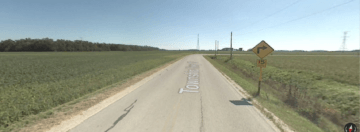

I had been hauled out to that old house in Dowling many times. Those road trips in the late Sixties were always momentous occasions for an eight-year-old me. Mom and Dad would load the kids into the backseat of the Ford Fairlane 500, and Dad would speed us down the main street of their old neighborhood on the southern outskirts of Toledo, immediately cross over into Wood County (old oil country), pass a trailer park on the left, then it was nothing but cornfields, soybean fields, farmhouses, silos, and railroad tracks for miles. Several miles out, Tracy Road diminished to what seemed a mere cow path slathered over with asphalt–and then suddenly dead-ended at a great curve to the west. This barren curve left a lasting impression on me as the End of Ohio (it wasn’t): From this point on, I thought, it’s nothing but cornfields and tornadoes.

Upon arriving at Grandma’s wreck of a house, I was always fascinated by the rattling, green iron hand pump that stood on a well cover just outside the back door. You worked the handle and actually got water to come out of the ground. Grandma would pump cooking water, washing water, drinking water out of that pump, as there was not a single water pipe in that house. Basins of water were filled at the pump, brought in to the sink, and then dumped out into the yard. That handpump, as well as the outhouse privy behind her little barn packed full of junk, had become talismans to me, symbolizing my great grandmother’s self-sufficiency. Imagine my surprise when I met the man who would become my husband, and the first time I walked out the side door of the big Maine barn where he kept his horses, I saw this:

Grandma made us tea and toasted bread slathered with homemade elderberry jam scooped out of a glass jar with a plug of paraffin wax on top. She presented Mom and Dad with a bottle of her homemade wine. Blanche’s dandelion wine became rather notorious in our household. The bottle she had given to my parents sat in a high cabinet for years, untouched, probably because it was sweet and not to the liking of my Stroh’s-drinking Dad. The bottle fascinated me, though. It was a clear glass bottle with a metal screw cap. And the liquid inside was so yellow, the essence of the dandelion flower. I barely knew what wine was, so I got a chair and stood on it to get access to the cabinet, and I tasted that limpid, yellow liquid. It was indeed sweet! And it had that alcoholic bite that was so compelling. After tasting it, I screwed the cap back on and put the bottle back exactly as I found it.

I did this a couple of times. Maybe three. Or four, who knows. But I always put the bottle back exactly where I found it.

One day my dad had to search that cabinet for something. He held the bottle out and looked at it. “Hey, Barbie,” he called out to my mother. The volume of his voice was rather raised, as if he were instead announcing something to the household. “What happened to Grandma’s dandelion wine?”

“I don’t know,” mom said.

He looked around and started laughing. “Somebody’s been drinking it. I didn’t drink it, you didn’t drink it. So who did?” Then he looked at me. “Hey, Mikey. Do you know what happened to Grandma’s dandelion wine?”

I had a theory, which I would regret telling him. “Maybe it evaporated?” This produced laughter such as I had never heard.

*

In 1923 at age 24, Grandmother Blanche eventually did settle down and get married, 7-year-old and 5-year-old sons in-hand. Somehow, she had met Frank S________ from Huron, Ohio, and married him in Cleveland. He was a World War I veteran, slightly injured in the Battle of Verdun. How did she meet such a guy? My mother told me, in the midst of another conversation, that the two had a female ancestor in common: Her grandmother turned out to be his mother. Had the half-uncle returned from the war to claim his childhood sweetheart? We will never know.

Their marriage lasted sixteen years: Frank died of tuberculosis in Arizona at the age of 43, and Grandma ended up right back at her father’s little house in Dowling, where it all had begun. Sometime later, she met her “handy man,” Melvin, and listed him on the 1950 Middleton, Ohio census as “lodger.”

How important are these sordid details? Shouldn’t the dirty past be allowed to be forgotten? The villain Iago’s insight in Othello comes to mind:

In Venice [wives] do let God see the pranks

They dare not show their husbands; their best conscience,

Is not to leave’t undone, but keep’t unknown. (3.3.205-7)

DNA now lets us see that once permitted only to “God.” It’s interesting that modern genetic analysis is so good at solving these ancient, intractable riddles. It’s interesting to learn, too, that some segments of my family’s DNA go back to a Civil War veteran, who was John Dennis’s father. But the thing I most wanted to learn about Grandma is the very thing I cannot know–that is, whether these affairs of the heart were consensual or not. I hope they were. Still, none of this mattered to me in the least growing up. It doesn’t matter what the sex lives of our progenitors were like, only that they happened. We Homo sapiens celebrate our relatedness to the hypothetical Mitochondrial Eve (circa 140,000 BP) and not because she was a virgin.

Family histories are dispersive: The further back we go, the more the number of progenitors increases, even as genetic relatedness decays exponentially, until we find we’re all related to the same people. Much beyond the point where the sepia-toned photographs and daguerreotypes stop turning up, genealogy, for all its emotionally satisfying reasons, ceases, and we end up with mere lists of names. If we search back far enough, we will find we all issue from the same pool of old whores and bastards.

Here’s the main takeaway about my crazy-ass, prodigal great grandmother: I loved her. I loved her sparkly, horn-rimmed glasses and her gray hair held up by bobby pins. I loved that mouth so enveloped in wrinkles it looked just like the top of a closed duffel bag. I loved her tiny kitchen in Dowling, her purple jams and jellies stored in glass jars with the thick wax seals on them. I loved the tall, rattling hand pump at the well outside her kitchen door. Her dandelion wine was delicious. As a city boy, this stuff seemed countrified and rather romantic to me, holdouts from Ohio as the Wild West. I now recognize it all as signs of a widow’s abject poverty.

Let it be known that my grandmother Blanche suffered as a young woman, born to a poor oil pumper, with two illegitimate boys on her hands; later existing under the stigma of a half-uncle as a husband; and living out her days in the shadow of a live-in “handy man.” But no one talked about it. Just as no one ever told me that I lived on top of what was once the world’s largest oilfield, and that the early drillers and pumpers let their oil foul farmers’ fields and fishing streams. We have seen how completely those who depleted the Lima-Indiana trend in Ohio were forgotten, their derricks and tanks and pump houses dismantled and disintegrated. Forgetting is as easy as pie, apparently, restoration all but impossible. What’s gone is gone forever.

How much does memory matter? I’m afraid we don’t have much say. It all just evaporates.

_______________

Photographs by the author.