by Marie Snyder

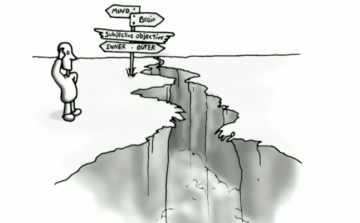

Freud got some things right, and this isn’t a post to slam him. But he understood the whole concept of the unconscious mind upside-down. It’s a lot like Aristotle’s science, with the cause and effect going in the wrong direction. It’s still pretty impressive how far they got as they laid the foundations for entirely new fields of study. I assimilated most of what’s below from neuropsychologist Mark Solms’s 2019 Wallerstein Lecture. It’s fascinating, but over three hours long, and he talks really fast! I’m just a novice in this field of affective neuroscience, and I don’t know enough to be sure his confidence in this theory is warranted, but it’s a really interesting way to understand ourselves.

Freud got some things right, and this isn’t a post to slam him. But he understood the whole concept of the unconscious mind upside-down. It’s a lot like Aristotle’s science, with the cause and effect going in the wrong direction. It’s still pretty impressive how far they got as they laid the foundations for entirely new fields of study. I assimilated most of what’s below from neuropsychologist Mark Solms’s 2019 Wallerstein Lecture. It’s fascinating, but over three hours long, and he talks really fast! I’m just a novice in this field of affective neuroscience, and I don’t know enough to be sure his confidence in this theory is warranted, but it’s a really interesting way to understand ourselves.

Here’s the gist of it.

Freud figured that the conscious part of our mind, the part that’s aware of our world and ourselves, was something that could be located in the brain, but he placed it in the cerebral cortex, the outermost area that does all the thinking. That makes sense because it’s how we connect to the outside world. However, according to Solms, the conscious part is actually way in the innermost region of our brain at the upper part of the brain stem. This has been backed up with studies on people with encephalitis that have found that it’s not essential to have a cortex in order to have emotional responses and an awareness of the world and self. When neuroscientist Jaak Panksepp had his students guess which rats didn’t have a cortex, they guessed incorrectly because the rats missing this intellectual part of their brain were friendlier, more lively and interactive; they didn’t have a cerebral cortex inhibiting their movement toward total strangers much like happens with the subdued inhibitions of friendly drunkenness.

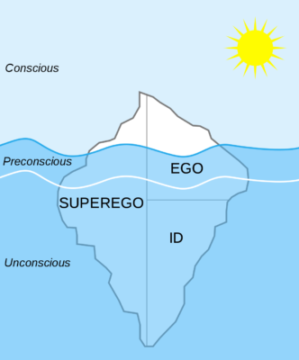

So Freud got the placement wrong. But even more important is which parts of us are within our conscious awareness. He famously divided our mind into three: id, ego, superego, much like Plato’s tripartite soul, and deduced that the id – our drives for pleasure – were entirely unconscious. But Solms explains that many in the field today argue that our affective center, the forces that push us toward pleasure and away from pain, is necessarily conscious in order to make us aware of our needs. And then decision making, which happens in the cerebral cortex, is mainly – like, 95% – automatic, without consciousness.

So Freud got the placement wrong. But even more important is which parts of us are within our conscious awareness. He famously divided our mind into three: id, ego, superego, much like Plato’s tripartite soul, and deduced that the id – our drives for pleasure – were entirely unconscious. But Solms explains that many in the field today argue that our affective center, the forces that push us toward pleasure and away from pain, is necessarily conscious in order to make us aware of our needs. And then decision making, which happens in the cerebral cortex, is mainly – like, 95% – automatic, without consciousness.

How can that be? We’re all aware of thinking right this moment, right? It all has to do with the efficiency of our memory systems. Read more »

Ntozake Shange, right, with Janet League in her play “For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow Is Enuf,” 1976. Bettmann/Getty Images

Ntozake Shange, right, with Janet League in her play “For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow Is Enuf,” 1976. Bettmann/Getty Images

obscure, often extraordinary abilities of animals and plants. Today, let’s look at a few more:

obscure, often extraordinary abilities of animals and plants. Today, let’s look at a few more:

reading “GPT for Dummies” articles. Some were more useful than others, but none of them gave me what I wanted. So I started poking around in the technical literature. I picked up a thing or two, enough to issue a working paper,

reading “GPT for Dummies” articles. Some were more useful than others, but none of them gave me what I wanted. So I started poking around in the technical literature. I picked up a thing or two, enough to issue a working paper,  Google the phrase “is it time to care about the metaverse?” and there are a wealth of articles, mostly claiming that the answer is yes! Are they right?

Google the phrase “is it time to care about the metaverse?” and there are a wealth of articles, mostly claiming that the answer is yes! Are they right?  Like most people, I have been baffled, mystified, unimpressed and fascinated by

Like most people, I have been baffled, mystified, unimpressed and fascinated by

1. In nature the act of listening is primarily a survival strategy. More intense than hearing, listening is a proactive tool, affording animals a skill with which to detect predators nearby (defense mechanism), but also for predators to detect the presence and location of prey (offense mechanism).

1. In nature the act of listening is primarily a survival strategy. More intense than hearing, listening is a proactive tool, affording animals a skill with which to detect predators nearby (defense mechanism), but also for predators to detect the presence and location of prey (offense mechanism). Njideka Akunyili Crosby. Still You Bloom in This Land of No Gardens, 2021.

Njideka Akunyili Crosby. Still You Bloom in This Land of No Gardens, 2021.

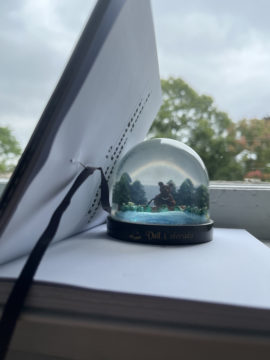

A metal bucket with a snowman on it; a plastic faux-neon Christmas tree; a letter from Alexandra; an unsent letter to Alexandra; a small statuette of a world traveler missing his little plastic map; a snow globe showcasing a large white skull, with black sand floating around it.

A metal bucket with a snowman on it; a plastic faux-neon Christmas tree; a letter from Alexandra; an unsent letter to Alexandra; a small statuette of a world traveler missing his little plastic map; a snow globe showcasing a large white skull, with black sand floating around it.

I liked to play with chalk when I was little. Little kids did then. As far as I can tell they still do now. I walk and jog and drive around town for every other reason. Inevitably, I end up spotting many (maybe not

I liked to play with chalk when I was little. Little kids did then. As far as I can tell they still do now. I walk and jog and drive around town for every other reason. Inevitably, I end up spotting many (maybe not