by Eric Bies

I liked to play with chalk when I was little. Little kids did then. As far as I can tell they still do now. I walk and jog and drive around town for every other reason. Inevitably, I end up spotting many (maybe not as many, but a good many) of them doing as I did: crouching between buildings, hunkering down on driveways and sidewalks to draw mommies and daddies and monsters; moons and suns; circles and squares. One minute they’re sketching their darling doggy; the next, they’re dreaming up cross sections of skyscrapers to hop across their faces. A very little one down the block, crab-walking with a piece of pink clasped in his left hand, practices divination with squiggles like the entrails of a bird. Recently, the rain has washed it all away, but only for the moment.

I liked to play with chalk when I was little. Little kids did then. As far as I can tell they still do now. I walk and jog and drive around town for every other reason. Inevitably, I end up spotting many (maybe not as many, but a good many) of them doing as I did: crouching between buildings, hunkering down on driveways and sidewalks to draw mommies and daddies and monsters; moons and suns; circles and squares. One minute they’re sketching their darling doggy; the next, they’re dreaming up cross sections of skyscrapers to hop across their faces. A very little one down the block, crab-walking with a piece of pink clasped in his left hand, practices divination with squiggles like the entrails of a bird. Recently, the rain has washed it all away, but only for the moment.

The Englishman G. K. Chesterton, one of those writers who wrote a lot of everything—novels about men with names like Thursday and Innocent Smith, biographies of Francis and Aquinas, a long poem about the Battle of Lepanto, detective stories Borges loved—also liked to play with chalk.

In “A Piece of Chalk,” one of many memorable articles written for the Daily News in the first years of the last century, Chesterton recounts a morning outing while on vacation.

Armed with six brightly colored pieces of chalk and a slim stack of brown paper, he decamps from his lodgings in a Sussex village for the “great downs.”

I crossed one swell of living turf after another, looking for a place to sit down and draw. Do not, for heaven’s sake, imagine I was going to sketch from Nature. I was going to draw devils and seraphim, and blind old gods that men worshipped before the dawn of right, and saints in robes of angry crimson, and seas of strange green, and all the sacred or monstrous symbols that look so well in bright colours on brown paper. They are much better worth drawing than Nature; also they are much easier to draw. When a cow came slouching by in the field next to me, a mere artist might have drawn it; but I always get wrong in the hind legs of quadrupeds. So I drew the soul of a cow; which I saw there plainly walking before me in the sunlight; and the soul was all purple and silver, and had seven horns and the mystery that belongs to all beasts.

A devoted Catholic, Chesterton knew the Bible backward and forward. But even those possessing only the barest mental sketch of that compendium of ancient documents know that God created the universe in six days; that the animals mounting the ark’s gangway went two by two; that Jesus kept twelve disciples and rose from the dead on the third day. In short, most of us know, as Chesterton knew well, that the Bible is a book of numbers. In marking the legitimacy of those numbers we make inroads toward Chesterton’s unique brand of euphemism. Take a look at that chalky cow once more: the seven horns are more than horns. They are the seven trumpets of the Apocalypse.

Of course, the trumpet as we know it represents a recent—and therefore rather rare—innovation. For most of human history we drummed with femurs and blew our breath through the tapering shapes that crowned certain skulls (as witness Jewish rabbis making ancient sounds on the horns of rams to this day). It is amusing to consider the ramifications of a pun, but we need not wonder in which sense St. John composed the musical sections of his Book of Revelation. The word employed stands for a contemporary instrument of hammered bronze.

John envisioned the end of the world as a complicated series of steps, each step signaled by one of seven angels manning one of seven trumpets, bugles, or, yes, horns.

1. When the first angel presses lips to the mouthpiece of the first horn and blows the earth will be showered with immense hailstones. Fire will fall from the sky, too, and blood, and a third of the planet’s population of trees will topple. Every blade of grass will perish.

2. When the second angel sounds off, we are told that “a great mountain burning with fire”—something like the asteroid that did in the dinosaurs—shall be “cast into the sea.” A third of the seawater will turn to blood, and a third of the sea creatures (probably those submerged in the blood) will die. Every third seafaring vessel will break into pieces.

3. The third angel, like Zeus serving up vengeance for Helios, calls down a great discrete projectile from the heavens, not a white-hot bolt of lightning but a “great star” by the name of Wormwood—more agent than asteroid—who terrorizes the rivers, poisoning them and the men that drink from them.

4. The fourth angel’s horn blasts away “the third part” of the sun, the moon, and the stars, so that the light of night and day, rather than simply dimming in kind, grows strangely shorter, as though the sun metes out its lumens like a jug its juice to a glass, filling only two now, not three. And an angel hurtles through heaven, shouting: Woe, woe, woe, to the inhabiters of the earth by reason of the other voices of the trumpet of the three angels, which are yet to sound!

5. The fifth angel makes a big shrill sound, so that another thoughtful star falls to earth. This one, nameless, ambles over to the Bottomless Pit and—creeeeaaaak—opens it up. Smoke billows out, and out of the smoke careen sky-obscuring hordes of locusts. The locusts have men’s faces framed by long hair beneath golden crowns. Their mouths are full of hard sharp lion’s teeth. They wear breastplates of iron and brandish stinging scorpion tails. Their purpose is to harry and put to rout, but not to kill, the men they find, and they are the first woe.

6. The sixth angel trumpets impressively, letting loose the four angels bound at the bottom of the Euphrates, who, gaining the crumbling banks and surveying the vast sweep of land at their disposal, summon a mounted force of “two hundred thousand thousand” cavalry soldiers. Like the locusts, their horses wear breastplates. Also like the locusts, their horses are monsters of frightful concatenation: someone has swapped the tail with the head of a serpent, and the head with the head of a lion. These horse-lion-serpents’ mouths fume with brimstone and smoke, and breathe fire. A third of humanity is, thus, crushed underfoot, cooked by fire, and choked to death by something worse than fresh asphalt. That is the second woe.

Forget, for the moment, the seventh angel, the final so-called woe. (So-called because it has something less to do with violence and more to do with goodness, the marriage of Heaven and Earth, a new Jerusalem.) Forget that because I have a woe of my own. Something is awry. I don’t know what exactly, or where in the process of the thing the movement away from perfection has been accomplished so decisively. But one knows something is awry when the paper—in this case the Times Literary Supplement, a weekly—keeps showing up two weeks late. I went down to the post office a couple of months ago to report that I hadn’t been receiving this weekly in a weekly fashion. They were apologetic and reassuring, and a week later three issues filled out my slender mailbox. I read them excitedly. But before long something again was awry. I tried calling the TLS; they told me that each issue had, in fact, been shipped on schedule. They suggested I try my local post office. Then, suddenly, the living of life made itself grand and encompassing, and so I forgot about my minor woe. As the weeks went by I would remember, on occasion, and forget all over again. Eventually new and old issues began to arrive, then something would go awry again. I don’t know how to describe the current state of the thing. Just yesterday, February 17, I received the February 3 issue. It is true that I have been reading it excitedly—almost as excitedly as I read the January 27 issue, which had arrived rather speedily on or around February 3. In that wonderful issue, which did much to soothe my minor woe, Susan Owens, reporting from Chichester on the latest art exhibition at Pallant House Gallery, sparked an inclination to travel to an area I’d read about but never been.

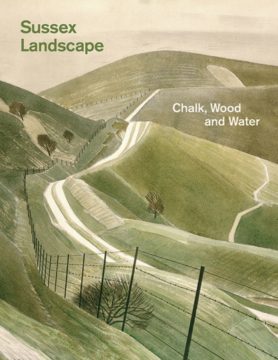

Virginia Woolf thought the whale-like bulk of the Sussex downs “too much for one pair of eyes.” Sussex Landscape: Chalk, wood and water answers her misgivings with different views of the famous hills, trees, cliffs, and beaches by more than fifty artists.

Virginia Woolf thought the whale-like bulk of the Sussex downs “too much for one pair of eyes.” Sussex Landscape: Chalk, wood and water answers her misgivings with different views of the famous hills, trees, cliffs, and beaches by more than fifty artists.

Apart from geography, one of the key constraints of the exhibition is chronology: all of the work on display must have been created on or after the year 1900. That is, mostly all of the work. The most recognizable names perforce break that rule, for Sussex Landscape includes paintings by J. M. W. Turner and John Constable. Even William Blake, who did a series of engravings to illustrate Virgil’s Pastorals, makes an appearance.

But what about Chesterton? Where are his devils and seraphim, his seas of strange green, his soul of a cow sketched out from a spongy seat upon those very downs?

We don’t know what became of his illustrations. What we do know is that he left his lodgings that morning with six pieces of chalk. At a crucial moment in the artistic process, he realized he was missing a seventh.

I sat on the hill in a sort of despair. There was no town near at which it was even remotely probable there would be such a thing as an artist’s colourman. And yet, without any white, my absurd little pictures would be as pointless as the world would be if there were no good people in it. I stared stupidly round, racking my brain for expedients. Then I suddenly stood up and roared with laughter, again and again, so that the cows stared at me and called a committee. Imagine a man in the Sahara regretting that he had no sand for his hour-glass. Imagine a gentleman in mid-ocean wishing that he had brought some salt water with him for his chemical experiments. I was sitting on an immense warehouse of white chalk. The landscape was made entirely of white chalk. White chalk was piled more miles until it met the sky. I stooped and broke a piece of the rock I sat on: it did not mark so well as the shop chalks do, but it gave the effect. And I stood there in a trance of pleasure, realising that this Southern England is not only a grand peninsula, and a tradition and a civilisation; it is something even more admirable. It is a piece of chalk.