by Tim Sommers

“Cleave,” “buckle,” and “dust” are contranyms. They are their own opposites. To dust means to remove, or sprinkle, with dust. To buckle means to collapse or secure. To cleave means both to divide and to stick to tenaciously.

In that spirit, an astro-turf Federalist Society group, opposing affirmative action and pro-active diversity in college admissions, calls itself “Students for Fair Admissions.” The Supreme Court is on the brink of using two upcoming cases brought by Students for Fair Admissions – SFA v Harvard and SFA v the University of North Carolina – to end the last vestiges of any attempts to address discrimination in the college admissions process.

One of the most widely-quoted slogans in Supreme Court history – right up there with ‘You shouldn’t shout fire in a crowded theatre’ and ‘I can’t define obscenity, but I know it when I see it’ – is “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.”

This approach to equal protection and fair equality of opportunity suggests that the way to address racial discrimination is to not see race, to be, metaphorically at least, color-blind. This is called the “categorization” approach to jurisprudence about race and it echoes the ‘Don’t say gay’ law in DeSantis’ Florida. It’s the ‘Don’t say race’ approach. (Also, the ‘Don’t say sex,’ but here I’ll stick with race, though I would be happy to discuss sex and other protected categories in comments.) Can we solve racism by being blind to race? Well, can we end discrimination against people with mobility challenges by not seeing wheelchairs? Read more »

When we speak about identity, we usually have in mind the various social categories we occupy—gender categories, nationality, or racial categories being the most prominent. But none of these general characteristics really define us as individuals. Each of us falls into various categories but so does everyone else. To say I’m a straight white male puts me in a bucket with millions of others. To add my nationality and profession only narrows it down a bit.

When we speak about identity, we usually have in mind the various social categories we occupy—gender categories, nationality, or racial categories being the most prominent. But none of these general characteristics really define us as individuals. Each of us falls into various categories but so does everyone else. To say I’m a straight white male puts me in a bucket with millions of others. To add my nationality and profession only narrows it down a bit.

There are two possible attitudes towards Scripture. One is to regard it as the direct and infallible word of God. This leads to certain problems. The other one, equally compatible with devotion, is to regard it as the recorded writings of men (it almost always is men), however inspired, writing at a specific time and place and constrained by the knowledge and concerns of that time. This invites deeper study of what was at stake for the writers, the unravelling of different narrative strands and voices, and discussion of whatever message the Scriptures may have for our own times. I expect that most readers here will adopt the second approach, while those who adopt the first are not to be dissuaded by mere rational argument, so why am I even discussing it?

There are two possible attitudes towards Scripture. One is to regard it as the direct and infallible word of God. This leads to certain problems. The other one, equally compatible with devotion, is to regard it as the recorded writings of men (it almost always is men), however inspired, writing at a specific time and place and constrained by the knowledge and concerns of that time. This invites deeper study of what was at stake for the writers, the unravelling of different narrative strands and voices, and discussion of whatever message the Scriptures may have for our own times. I expect that most readers here will adopt the second approach, while those who adopt the first are not to be dissuaded by mere rational argument, so why am I even discussing it?

About a third of the way through a first-year humanities honors course, one of my more engaged and talkative students pulled me aside after class for a private chat. She waited, clearly anxious, while the rest of her classmates filed out and then turned to me with her eyes already filling up with tears.

About a third of the way through a first-year humanities honors course, one of my more engaged and talkative students pulled me aside after class for a private chat. She waited, clearly anxious, while the rest of her classmates filed out and then turned to me with her eyes already filling up with tears.

My father, the son of Italian immigrants, was a member of the working class. There were things within reach, and things that were not in reach, and he accepted this. He never pushed his children to broaden their horizons, and would have been satisfied to see them in traditional working-class vocations. When I came home from school eager to show off my grades, he poked fun at me. The prospect of pursuing an intellectual career was alien to him; in his view, taking out student loans to go to college or university was a way for banks to trap the “little guy.” When I presented him with the papers, he refused to sign. There was no discussion. I eventually moved out and managed to get my BFA anyway, and when I wound up as a finalist for a Fulbright, the doctor who performed the general checkup required by the awarding commission—I was still covered by my father’s Blue Cross plan, but only because I was still technically a dependent and it didn’t cost him anything—took him aside and told him that a Fulbright would be “quite a feather in your daughter’s cap.”

My father, the son of Italian immigrants, was a member of the working class. There were things within reach, and things that were not in reach, and he accepted this. He never pushed his children to broaden their horizons, and would have been satisfied to see them in traditional working-class vocations. When I came home from school eager to show off my grades, he poked fun at me. The prospect of pursuing an intellectual career was alien to him; in his view, taking out student loans to go to college or university was a way for banks to trap the “little guy.” When I presented him with the papers, he refused to sign. There was no discussion. I eventually moved out and managed to get my BFA anyway, and when I wound up as a finalist for a Fulbright, the doctor who performed the general checkup required by the awarding commission—I was still covered by my father’s Blue Cross plan, but only because I was still technically a dependent and it didn’t cost him anything—took him aside and told him that a Fulbright would be “quite a feather in your daughter’s cap.”

Sughra Raza. Just a Street Corner. Boston, 2022.

Sughra Raza. Just a Street Corner. Boston, 2022.

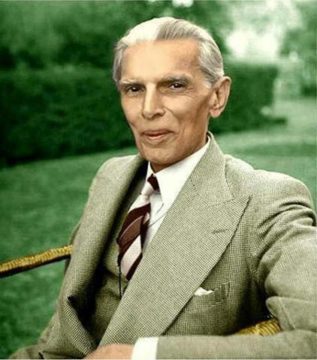

Mohammed Ali Jinnah’s Last Visit to Kashmir 10 May – 25 July 1944

Mohammed Ali Jinnah’s Last Visit to Kashmir 10 May – 25 July 1944

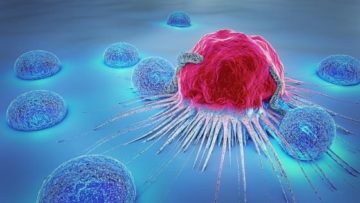

No metaphor for cancer does it justice. As a medical oncologist and cancer researcher, I struggle constantly with how people perceive cancer. Until a person suffers from it or sees a loved one suffer from the devastation of this disease, cancer remains an abstract term or concept. But it is an abstract concept that kills 10 million people around the world every year. Ten million people every year. How do we get people to understand that this is a lethal disease that deserves attention. That deserves more funding. That deserves more minds thinking about how to stop the continual suffering that metastatic cancer causes.

No metaphor for cancer does it justice. As a medical oncologist and cancer researcher, I struggle constantly with how people perceive cancer. Until a person suffers from it or sees a loved one suffer from the devastation of this disease, cancer remains an abstract term or concept. But it is an abstract concept that kills 10 million people around the world every year. Ten million people every year. How do we get people to understand that this is a lethal disease that deserves attention. That deserves more funding. That deserves more minds thinking about how to stop the continual suffering that metastatic cancer causes.