by David S. Greer

1And the Lord spake unto Moses, Go unto Pharaoh, and say unto him, Thus saith the Lord, Let my people go, that they may serve me.

2And if thou refuse to let them go, behold, I will smite all thy borders with frogs.

3 And the river shall bring forth frogs abundantly, which shall go up and come into thine house, and into thy bedchamber, and upon thy bed, and into the house of thy servants, and upon thy people, and into thine ovens, and into thy kneading troughs.

4 And the frogs shall come up both on thee, and upon thy people, and upon all thy servants.

King James Bible, Exodus 8

The negative reputation suffered by frogs during Biblical times hasn’t improved much since. Macbeth’s three witches made a point of tossing into their bubbling cauldron not only toe of frog but also an entire venomous toad (a frog by another name). In later fairy tales, princesses kissed frogs with reluctance, and only when required to break a spell. Even today, the ickiness factor of frogs remains high for anyone leery of creepy-crawlies, even though more frogs means fewer spiders. And most people still wouldn’t welcome a clammy frog in their bed, let alone in their kneading trough.

The American bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus), to name but one of the planet’s 5,000-plus frog species, has a face no one but a mother could love. And when that face originates from just one of 20,000 eggs, the mother can hardly be blamed for failing to even recognize her offspring’s features, a fact that might go a long way towards explaining why American bullfrogs have a fondness for eating their progeny, whether at tadpole stage or in froggy maturity. Life as a carnivorous frog usually means no exceptions for children or cousins or aunts. Eat or be eaten is the watchword of the frog and not a bad rule to remember for species hoping to survive and evolve to some more advanced form of life. It has always been thus.

Whatever your views on the superficial appearance of frogs, consider what a marvel of evolution they are. For starters, a frog can breathe and drink through its skin, thus freeing up its mouth for eating without unnecessary interruption. Frogs are engineered for eating as cheetahs are for speed or swallows for flight or honeybees for making honey. When you’re virtually all mouth, it pays to make the most of it, and frogs have, taking full advantage of a few hundred million years of evolution to perfect that ability. A massive mouth is not the only tool a frog brings to the table to facilitate eating. Its tongue is not attached to the back of the mouth, as it is in humans, but to the front, enabling it to protrude quickly and at a great distance to seize prey. And if the prey is bulky or difficult to swallow, the frog’s eyes descend into its skull, making a bulge in the roof of the mouth that helps squeeze the food towards the back of the throat—which is why frogs and toads blink when they eat.

When it comes to eating, frogs are up to any challenge. If it fits even partway into their gape (a widely open mouth), it’s fair game. Dr. Gavin Hanke, Curator of Vertebrate Zoology at the Royal British Columbia Museum, recounts an episode in which a bullfrog attempted to swallow an almost fully grown duck. The bullfrog went hungry (the duck didn’t quite fit) but survived; the teal was not so fortunate, avoiding being eaten but drowning anyway.

Consider as well the creativity shown by the frog in the matter of reproduction. The average frog lays its eggs, having found an agreeable male to fertilize them, then abandons them. A very small percentage of the tadpoles that emerge from the eggs successfully swim the gauntlet of creatures with a taste for tadpoles and in due course transform into frogs. When you lay 20,000 eggs, it only takes a few survivors to count as success. Other frogs lay fewer eggs but take elaborate precautions to ensure a high survival rate. The female pipa toad, after laying eggs, embeds them in the skin of her back to keep them safe (with a little help from her mate). In the case of the midwife toad, it’s the male that guards the eggs by twining them around his legs and carrying them until they’re ready to hatch. The male of a type of Chilean frog takes an altogether different approach, scooping up the eggs laid by a female and depositing them in his vocal sac, where they safely develop until the baby froglets emerge from his mouth.

The external eardrum—patches of tight skin that vibrate sensitively in response to sound and enable a frog to sense your presence long before you’re an imminent threat—came relatively late in the frog’s evolution, perhaps only 100 million years or so ago, when our human ancestors were still tree-dwelling lemurs or something similar.

From that perspective, frogs are far more advanced in evolutionary terms than humans in the complexity and variety of their adaptations for life in different environments. What really distinguishes humans, of course, is their ability to cause a great deal of harm to other species with minimal effort, usually in the guise of doing something useful (such as converting wetlands for a “better” use, killing weeds or bugs that might inhibit crop production, etc.). Which is largely why a 2004 worldwide survey of amphibian populations (frogs, toads, salamanders, newts) found roughly one-third of amphibian species to be at risk of extinction globally—a number that grows with each passing year.

Frogs’ most valuable evolutionary traits can make them most vulnerable to human-caused harm. The permeable skin that enables them to absorb oxygen and fluid is ideally predisposed as well for the absorption of pollutants such as pesticides and herbicides that can rapidly deplete amphibian populations.

The wetlands vital to frogs for breeding success—and, as importantly, vital as carbon depositories essential for mitigating climate change—remain a constant target for conversion for agriculture and other forms of development, a constant threat exacerbated by the periodic and in some cases permanent drying up of wetlands as a consequence of extreme weather events precipitated by human-caused climate change.

The impact of the introduction of invasive species adds another significant layer to the threat to frog populations. Whereas pollution and wetland conversion and climate change are largely the product of corporate activity, the spread of invasive species can be attributed in large part to the actions of individuals either ignorant of or indifferent to the consequences of introducing exotic species into ecosystems lacking natural defenses against the potential harm posed by invasions, whether by competition with or predation of native species. Ecosystems are finely tuned systems in which every component has its place, essential in the sense that each component depends on and is needed by other components. The sad reality is that ecosystems take millions of years to evolve and can be undone in a relative instant, an introduction of an invasive species being equivalent to throwing sand into a fine piece of machinery.

It’s much easier to release exotic creatures into an ecosystem that has no defences against its invasion than it is to round them up afterwards. The far greater challenge is to convince people that, however well intentioned their motivations, introducing invasive species is likely to occasion immensely greater harm to the community than any short-term benefit for the individual. This, of course, presupposes that individuals grant equal or greater value to community benefits than to their own expected benefits—a tricky supposition at best.

***

Off the west coast of North America lies an inland sea sheltered from the open Pacific by Canada’s Vancouver Island and the American Olympic Peninsula. The hundreds of islands in the Salish Sea include a pair linked by a rickety one-lane bridge and known as North and South Pender islands in settler language and as SDȺY¸ES in the SENĆOŦEN language of the W̱SÁNEĆ indigenous people whose traditional territory covered much of the Salish Sea.

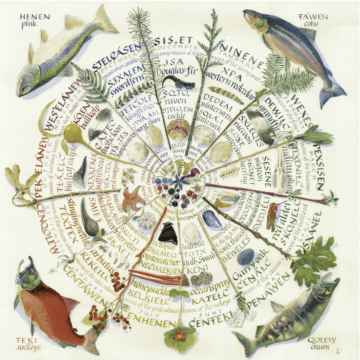

After the W̱SÁNEĆ people came to live on the islands, their prosperity depended on careful observation of the cycle of the seasons and particular events at each time of the year. When the ocean spray bloomed in May, they knew it was time to set out reef nets for sockeye salmon. The W̱SÁNEĆ people’s knowledge of natural relationships was communicated orally from one generation to the next and in recent years has been replicated in a visual representation as a 13 Moon Calendar that shows how people understand the interrelationships of events under each moon. Under the Frog Moon, WEXES, the shrill calls of armies of treefrogs (yes, that’s the real name for assemblages of frogs) in the wetlands heralded the turning of the tide that would deliver the annual herring bounty from the sea. The frog chorus told that the time was close for harvesting red seaweed and butter clams from the shore as well as herring spawn from kelp fronds.

Though the locals still refer to the frogs as treefrogs, the scientific community now knows them as the Pacific chorus frog, having determined that they are more properly placed in the genus Pseudacris (chorus frogs) rather than in the genus Hyla (treefrogs). Whatever you prefer to call them, the wintry night their clamorous mating song erupts, loudly echoing through the forest, is as sure a sign of spring on the west coast as the first appearance of robins is in the east. (The appearance of robins on islands of the Salish Sea is a bust as a sign of spring, as they migrate here from Alaska to spend the winter in a more temperate climate.)

Another underestimated evolutionary attribute of frogs is their ability to produce a very loud noise from an exceedingly tiny frame by swelling their throats or, in the case of some species, employing resonating sacs bulging from the corner of the jaws—yet another trick that took a few million years to perfect. The purpose, as so often with evolutionary developments, is solely to impress a member of the opposite sex. Pity the poor female whose ears are ringing with the sound of hundreds of amorous males holding forth at close range. How to choose? If doctoral candidates have already have spent countless patient hours on all fours in swamps examining this mystery, it has not to our knowledge yet been reported. Suffice it to say that the calls of myriad treefrogs calling in unison can be loud enough to make it difficult for humans to communicate without shouting.

Speaking of ribbets, an interesting factoid about Pacific chorus frogs is that theirs is the call heard in countless movies that use choruses of frogs to set the scene, whether that involves cowpokes hunkered around a fire beneath the stars or a courting lover about to burst into song on the lone prairie. Treefrogs were what Hollywood sound effects crews found in their backyards, so treefrog calls became the staple sound effect for movie settings far outside their range, and the fact that moviegoers came to expect treefrogs provided extra incentive for continuing to employ them for that purpose, regardless of factual accuracy.

There’s even a webpage devoted to listing movies in which treefrogs are heard where no treefrog has ever before set its sticky foot—films such as The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, The Last Picture Show, To Kill a Mockingbird and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. The horror movie Frogs even shows cane toads uttering Pacific chorus frog ribbets to intimidate terrorized citizens. This is akin to providing a man-eating Bengal tiger with the mew of a calico pussycat, but given that horror movies require a willing suspension of disbelief as a prerequisite for engagement, it probably doesn’t matter.

Once the mating season’s done, the chorus ends, and for the rest of the year all you’ll hear from the Pacific chorus frog is the rusty creaking door kre-ec-c-k of a solitary male secreted somewhere in a cedar or a salmonberry bush, sounding so loud and close you could swear you could touch it, though you’ll never find it if you try.

Meanwhile, other chorus frogs are silent but decidedly visible. For years I had a patch of dusty miller in a pot on my deck, and every August a couple of chorus frogs would come and sit the whole day long on its silvery leaves, their bright green and gold skin contrasting sharply against their pale perch. This year I decided to plant black-eyed susans on the deck to see if the frogs would come. Sure enough, one August day, there they were—two tiny juveniles about the size of my pinky fingernail, lurking among the golden petals, cleverly camouflaged as plant greenery, waiting to ambush some distracted spider or fly.

If any frog is cute enough to attract the kiss of a princess, the chorus frog is a likely candidate. The much beloved Kermit the Frog (more than twice as popular as Miss Piggy, to her apparent chagrin) bears a striking resemblance to a species of Costa Rican glass frog, so named because its skin is so translucent that its internal organs are visible, though it’s also possible to imagine that his invention might have been inspired by a Pacific chorus frog, the most common frog in the Pacific Northwest and the only frog native to the Pender islands in the Salish Sea. (The northern red-legged frog [Rana aurora] is found on surrounding islands—Saltspring, Mayne and Saturna—but has not been reported on the Penders.)

The Pacific chorus frog is considered to be a species of least concern under the IUCN conservation status categories, meaning that it’s not threatened with extinction. That could change in the long run if climate change threatens its habitat (availability of temporary wetlands) or if it’s threatened by the introduction of predatory invasive species.

***

A natural ecosystem is as finely tuned as a Swiss watch insofar as each of its components, no matter how innocuous, plays an important role in the functioning of the whole. Invasive species—species that don’t naturally occur there but arrive either through migration or through human intervention—can wreak havoc in an ecosystem either by competing with native species or, as in the case of a bullfrog, devouring them.

American bullfrogs are native to eastern North America and a scourge everywhere else. They began appearing on islands in the Salish Sea a few decades ago, possibly as a consequence of escapes from a farm raising bullfrogs for their meat. Bullfrogs were also once imported by aquatic garden supply companies for stocking backyard ponds. This was not a brilliant idea, in retrospect, but was a standard practice in times when people felt no need to give the integrity of ecosystems even a passing thought. The same might be said in future about the amount of attention given in recent years and even today to the importance of putting the brakes on climate change.

Frogs can only migrate to islands in the ocean through human intervention because they can’t survive in saltwater. People who transport bullfrogs to a previously bullfrog-free environment generally don’t think about the consequences. They may simply feel a sentimental attachment to the sound of croaking in their backyard pond. Unfortunately, all it takes is a single pair, a male and a female, to start the froggish equivalent of an out-of-control wildfire, especially if they have no natural predators in their new environment. Once a bullfrog population has spread, attempts to eradicate it typically have little success, especially if property owners with ponds containing bullfrogs refuse to cooperate. It was for precisely that reason that a conservation organization on Pender Island, after collaborating with other groups and government agencies to attempt to eradicate bullfrog populations, finally abandoned the effort.

To a bullfrog weighing close to two pounds, a tree frog is a tiny morsel, barely enough to whet the appetite. To date, there are reports of bullfrogs on only one of the Penders—North Pender Island. Will they in time cross the one-lane bridge to South Pender, as other invasive species have done before them? Time will tell. The chorus frog does have one potential protection against a bullfrog invasion. Whereas the bullfrog requires a year-round pool for reproduction through all stages to adulthood, the chorus frog needs only a temporary wetland, the result of winter rains. In addition, chorus frogs can move fairly quickly when threatened. The bullfrog’s fastest assets—its enormous mouth and lightning-fast tongue—may not be enough to overcome a chorus frog’s capabilities.

That may not be true, however, for another more nimble invasive species. The common wall lizard (Podarcis muralis), native to parts of Europe, is now distributed throughout much of North America and in recent years has spread rapidly through the area surrounding the Salish Sea. Residents of areas with long-time chorus frog populations report the woods becoming silent once wall lizards establish a foothold. Wall lizards, tiny as they are, are voracious feeders and lightning fast, and thereby potential predators of small creatures such as juvenile chorus frogs. And both wall lizards and bullfrogs are potential predators of the tiny and endangered sharp-tailed snake (Contia tenuis).

Like the bullfrogs, wall lizards rely on human transportation to gain access to islands. People who think of them as an exotic reminder of more southern climes, maybe something Mediterranean, might be tempted to transport them to their gardens, where a rock wall provides ideal habitat for rapid breeding and migration farther afield. Pender Island’s first verified wall lizard sighting was recently reported—a solitary male on the north island. Other reported sightings, on further investigation, have turned out to have been sightings of the native alligator lizard, which tends to be considerably larger than the wall lizard, with distinctive plate-like scales, heavier tails, stubby legs and toes, and a greyish brown colour with black peppering. But perhaps the most reliable clue to the identity of the lizard is its behavior when you approach it. Alligator lizards tend to rely on camouflage and remain still; wall lizards are far more skittish and likely to disappear in a flash as soon as you get close. For the time being, the chorus frog populations on the island appear to be safe from wall lizard predation—unless the male wall lizard that was spotted happened to have a mate that escaped detection.

Of course, there are many examples of the same species that is potentially threatened in one location becoming a threat in another. The Pacific chorus frog is a case in point, having emerged as an invasive species on Haida Gwaii, north of Vancouver Island. In this case the instrument of invasion was apparently a boy who moved there with his family and missed the sound of frogs so much that he released a jar of tadpoles or an egg mass. The frogs spread rapidly, and only time will tell what impact they have on Haida Gwaii ecosystems.

Invasive species are generally bad news for native species, and some invasives are far worse news than others. Wherever you happen to live, it pays to learn what you can about invasive species, determine which ones are most dangerous and how to identify them, and above all avoid inadvertently introducing them and discourage others from doing so. And always remember the cardinal rule: it is far easier to avoid releasing invasive or exotic species at the outset than it is to round them up afterwards.

***

Thanks to Dr. Gavin Hanke, Curator of Vertebrate Zoology at the Royal British Columbia Museum, for generous advice as well as photos of invasive wall and native alligator lizards. Thanks also to Bruce Tuck for his contribution of photos of American bullfrogs. See www.birdsinmyview.com for more Bruce’s work.