by Mike Bendzela

Hannah was a wide-horned, burgundy-red American Milking Devon heifer, with bug eyes and such a timid disposition you got the impression of a creature permanently bewildered. You could not approach her; she would just pace off to a corner of the barnyard pasture and stare at you from a distance. And she seemed never to blink: you swore she knew she was doomed.

Her adopted mother, Belle (full name: Colonial Williamsburg Belle), was just the opposite—outgoing, ornery, bright, also wide-horned and the burgundy red of the breed. We had had Belle a few years before we bought Hannah as a yearling from a Devon breeder. My husband, Don, had visions of hand-milking a small population of cows and selling the milk and the inevitable bull calves to neighbors and hobbyists. Such a prospect caused me to have visions, period.

But Hannah never calved.

We thought something was wrong with her from the time she was a young cow, when she attempted to nurse off Belle. Even though Belle already had her own calf to feed, she indulged the new yearling. Not even the spiked “weaner” that hung from Hannah’s nose like malevolent jewelry dissuaded her from Belle’s teat. She just learned to flip the weaning device up out of the way and twist her head in such fashion as to permit her access to Belle’s swollen bag.

The near-adult cow nursing off the adopted mother in the barnyard got to be something of a scandal. We even had to pen Belle up in the barn with her calf, Abe, to allow him an unmolested meal. Hannah literally had to grow out of it: After a time, she just could not fit her head and horns under the other cow anymore.

Stopped in her tracks

One September day, Hannah stood opposite me at the top of a small rise beside the barn, about a hundred-fifty feet away, under the largest ash tree on the property, just staring. Claudia was up there at her house at the time, and she said, “Something’s not right with Hannah.” Claudia is, for lack of a better descriptor, our landlord. It is a relationship that began back in the 1970s with my husband’s agreement with Claudia’s father, Claude, to restore the old Dow family farmhouse in exchange for tenancy. Claudia and her husband, Ken, took over care of the land and farm in the years after Claude and his sister/co-owner died, and here we are.

Hannah looked particularly perplexed. It was hard to place, but in addition to the doomed, bug-eyed look, she held her head tilted slightly upward toward the clouds, as if waiting for some notion to come to her. Any hint of contemplation in a cow is worthy of note; so, as she pointed her nose up, up, gazing off into her troubled future, I stopped what I was doing—that is, mending electric fence wire—and stared along with her.

Presently, she expelled a wracking cough: foam erupted out her mouth and spilled down her front, dripping in festoons from her chin. Her four hooves kept such purchase on the sod that the whole animal seemed anchored to the ground, like a wire tomato cage.

“Oh my God,” Claudia said.

I walked over to find Hannah in a sort of low-level distress, like a sleeping person at the onset of a terrible dream. A gurgling sound issued from deep within her, and foam drooled from her jaws in gobs, like yogurt. She sniffed a little. Then I remembered: The Wageners!

Earlier that day, I had scrabbled around on my hands and knees under the Wagener apple tree, picking up small, glossy, pink-red apples that I had hand-thinned from the tree in a last desperate attempt to size-up the remaining crop. I had tossed all these wasted apples into a bushel basket. Heritage Wageners have a deplorable bearing habit—they are rigidly biennial, over-cropping one year and bearing perhaps one apple the next. By aggressively thinning fruit from the tree, one hopes to not only improve fruit size but help the Wagener snap out of its biennial habit. It never works. One ends up tossing hundreds of immature fruits away, and as the remaining apples barely swell larger during the season, one realizes one has not thinned enough to make a difference. The Wagener is too precocious a bearer. I would eventually cut that tree down.

In my impatience to be rid of the apples and continue my fence-mending, I dumped the bushel over the electric wire for the cows and horses.

When you raise livestock, even as a hobby, you learn quickly that they are selfish brats, worse than two-year-olds. No matter that they get grain twice a day; no matter that they have abundant pasture and hay; when a snack flies over that fence wire, they all come a-running, as if Noah has just shouted, “All aboard!” They all want to be first. They all want to monopolize the food pile, even throwing their bodies sideways to block oncoming traffic, in this instance two horses—Sammy (a small draft horse), Cody (a retired Standardbred)—and five cows—Belle, Abe, Hannah, our neighbor’s Milking Shorthorn, Elsa Mae, and her heifer calf. They made short work of those little Wageners, grunting, stomping, throwing their heads (and horns) around, and probably swallowing apples whole to make sure no one else got any.

As Hannah stood before me now, gurgling, bug-eyed, foaming, I pictured a hard, little Wagener jammed into a tough, tight esophagus, like a cue ball in a garden hose.

Claudia advised I consult the Internet.

The Internet told me that our cow might indeed have an esophageal obstruction. The Internet reminded me to never feed whole apples or potatoes to cows, a fact I knew but which fact I had simply jettisoned from my brain in my rush that day, like a hairball. The Internet said further that my cow might die in as little as two hours.

Bad news, Bos

When my husband Don got home from work that afternoon, I said, “I think Hannah has a blockage.”

“What?”

I told him what had happened, took him up the hill beside the barn and showed him the cow—no change, still immobile and foaming.

“You’re not supposed to feed whole apples to cows,” he said.

We went inside the house, where I showed him the Internet.

Don and I perused veterinary sites and learned about “choke” and “bloat”: Cows’ stomachs are fermentation factories, and such factories give off lots of gases as waste products. When cows are not grazing or chewing their cuds, they are spending their days belching. Therefore, an obstruction of the esophagus (“choke”) is a very bad thing: the gases cannot get out, but that does not mean the fermentation factory shuts down for the day.

Hence, bloat.

I had visions of Thanksgiving Day floats, of Monty Python’s Flying Circus’s Mr. Creosote exploding in the restaurant.

We got Hannah chained up at her stanchion in the barn. Then we called the emergency veterinarian–on a Sunday. We said we thought we had a case of choke in a rare Devon milk cow.

In the meantime, Don offered Hannah assorted victuals—freshly cut hay, grain, green grass. She just coughed and slobbered in response.

How this mighty, Pleistocene beast hath fallen!

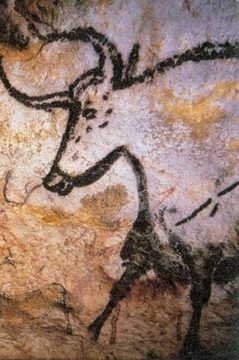

Some ten thousand years ago, during the Neolithic revolution in Northern Syria, Hannah’s ancestors, hunted by humans, began to be selected for smaller stature and docility, resulting in domesticated cattle, which continued to interbreed in Europe with the wild beasts. The last member of the primordial breed of cattle, the aurochs (“Ūr-ox”), went extinct in the 17th century, after several millennia of tampering by humans.

Its diminutive descendant, the Milking Devon, is a rare, “aboriginal” breed that has been in the United States for over four hundred years, originating from earlier breeds brought over from England by settlers. Something about the Devon’s wide horns and ornery nature makes me think of it as a thumbnail sketch of the mighty aurochs.

My husband enjoyed hand-milking his Devons. As a small breed, they are easily managed by a home farmer, not too difficult to feed and house. Our original cow, Belle, which we bought at three years old, gave us three calves over her lifetime–all bulls: Henry, who ended up being trained as an ox at Old Sturbridge Village, Massachusetts; Abe, whom we ate; and one stillborn bullcalf. When Belle began to decline–some time after Don had suffered a stroke and needed a break from milking–we sold her to a livestock dealer for meat.

Hannah had come to join Belle when Don wanted a second cow to milk. She was a yearling heifer, maybe two years old, never bred. We visited her at her breeder’s farm then had her trucked home. Motherly Belle took a shine to the new heifer in the barnyard, but Hannah turned out to be a handful; never properly weaned, she pestered Belle continually for milk. Over the years, we repeatedly had veterinarians artificially inseminate her, but she was never able to conceive. Then, like the Serpent in Eden, I fed her that damned apple….

Cattle call

The emergency vet’s pickup truck showed up in our dooryard much sooner than we anticipated. A petite but rugged young woman, Megan, got out and grabbed a big jump kit out of the back. “I had to come all the way down from China,” she said. She shouldered the bag and grabbed a pail and some tubing. “Took me just over an hour.”

She meant China, Maine, of course—Don calls it “farm country—but it might as well have been China. It still astonishes me to think that she made it to our little town in southern Maine in an hour. If she had gotten pulled over for speeding, our cow would have exploded.

The four of us—me, Megan, Don and Claudia—strode up the barn ramp, discussing assessments and options, me babbling my tale of the Wageners. When Megan saw the state that Hannah was in, she went immediately into action.

First, the cow had to be sedated, “But not too much,” Megan told us, as we did not want her to go down. The injection to Hannah’s neck took effect quickly: she became quiescent, slack-jawed; she stared at the wall of the barn, unblinkingly. Basically, not much changed. But we four had to stand around her, steadying her two-handedly, to make sure she would not go down.

Megan palpated the front of Hannah’s stocky neck and immediately found the Wagener. “It’s right here,” she said. We all took turns feeling up the cow’s long throat and gently squeezing the little apple encased in hide. “We need to get to work,” Megan said. She explained that she would feed a hose down Hannah’s throat to dislodge the obstruction. Then, to confirm success, she would push the hose further into Hannah’s first stomach to try and get the contents of the rumen to flow out into a bucket.

First, though, there was the bloat to contend with. Megan took out of her bag a device that reminded me of an ice pick, or a carpenter’s gimlet, such as those Don had strung on a wire loop in his workshop. This was a “trocar.” Megan held it in her fist and punched it through the cow’s hide, high up on the flank, toward the rear. Then, withdrawing it, she left in place a sort of valve—a “cannula”—to, as she said, “relieve the gas.” The three of us gaped on in shock: Hannah had become a cow-shaped innertube with a valve stem.

It became Don’s job to hold onto the cannula so that it would not slip out under pressure of the gas flow. “Yep,” he said, “smells like apples.”

Megan took a few moments to text somebody, read a response, then put the phone into the breast pocket of her shirt. “This will buy us some time,” she said, “but we have to work fast.”

Megan picked up the coil of gastric tubing and, with some work, got it to go down Hannah’s throat. She fed the hose in until it would go no further. Megan gripped the tube where it met Hannah’s lips, then withdrew it and measured the tube length against Hannah’s neck from the point where she gripped onto the tube. Nowhere near far enough to reach the first stomach. The measured length of tube ended right at the apple lump. “OK. Time to dislodge that obstruction.”

Megan fed the tube down Hannah’s throat and gently but firmly drew the tube back and plunged it forward, like a battering ram, to get that Wagener to continue on its way. The physicality of it was a bit of a shock: This animal was a thing with a thing lodged inside it. You had to use another thing and try to dislodge the thing inside the thing. We are all things.

Impasse

The Wagener would not budge. It was lodged so tightly that the end of the tube flexed upon impact, and Megan did not want to risk injuring Hannah’s esophagus. She determined she would have to go in arm-first and coax the obstruction along by hand.

As she rolled up her sleeve, she thought out loud about how to proceed. “She has a small mouth for a cow. I don’t want to hurt her. Or myself. One of us has to hold her mouth open somehow.”

“What about a speculum?” Don suggested, still holding onto that venting cannula in the cow’s back like a pipette. “You work with horses, right?”

“Let me check my truck,” she said.

While she was gone, Don explained that veterinarians use a speculum to hold open a horse’s mouth while they “float its teeth” with a file. This seemed a desperate remedy for our poor, stopped-up cow.

Megan came back with a stainless-steel device whose use was disturbing to contemplate. “Let’s give it a try,” she said. “We don’t have many other options.”

Claudia took over the cannula while Don assisted Megan with the speculum. I gently massaged Hannah’s throat, hoping the apple would just move through her gastrointestinal tract of its own accord.

The speculum in place, Megan ratcheted Hannah’s mouth wide open. She looked ghastly, comical, a techno-circus cow with a hole in it. Lucky for her to be doped up.

Megan placed her small hand into the cow’s mouth and, with a little turning and dancing around, managed to get in up to her elbow. “I’m in the esophagus.”

She spent a few moments reaching deeper, speaking gently to the cow, “Good girl, Hannah.” She was in up to her shoulder. The end.

“Mike—see if you can push up on her neck to shorten her esophagus.”

I got on my knees in front of Hannah, found the knot in her throat, and pushed upward against it with all my might.

“There it is,” Megan said. “Definitely an apple. I can feel it, but I can’t push against it.”

I shoved against Hannah’s neck until I could not shove anymore.

Megan withdrew her arm from the cow’s throat. Don offered to give it a try. He and Megan held their arms up together to compare lengths. He is a tall, skinny carpenter, his arm a mite longer than the vet’s.

Don reached in through the speculum and, like Megan, managed to screw his arm in right up to the elbow, then to the shoulder. “Yep, there it is. . . . Michael, push again.”

Having exhausted my arm strength, I bent under the cow’s neck and buried my shoulder into her throat, bearing my body strength against that Wagener.

“I can’t grab it or push it,” Don said.

He withdrew his arm and Megan tried again. As she reached deep into the cow, I made to stand up against that apple that poked into my shoulder.

She was quite the sport, that Megan. Fresh out of veterinary school, this was her first case of choke in a cow, and she was dealing with it like a champ. We would make an appointment with her again a few years later to examine Hannah’s reproductive tract. We had tried to have her inseminated artificially twice, but she never “settled,” or conceived. Because we were not exactly sure of Hannah’s origins, we feared she might be a freemartin, the infertile female companion of a male twin in utero. The next time we would see Megan, she would be shoulder-deep in the back end of the cow, feeling around not for apples but ovaries.

“I can flick my nail against it,” Megan said.

She withdrew her arm and showed us all a piece of apple in her hand about the size of a quarter, with that familiar, glossy pink-red skin, the flesh turning brown.

“Yay!” Claudia said.

Megan took up the tube again. “Maybe I can dislodge it now that it has changed shape.” She fed the hose smoothly down the cow’s prized-open mouth, like feeding a garden hose through a cellar window, as if she had been doing it all her life. The tube went in past the previous dead-end mark. As it continued further in, you could almost feel it going into that cow’s stomach. We all shouted in relief, “Hooray!”

“Wait a minute,” Megan said. “I won’t be happy until I see flow from the rumen.” She had me fetch a pail. She dropped the end of the hose into it. We all stared into the bucket: a deep-green ooze flowed out of the tube and pooled in bottom. “She’s free.”

“Phew!”

“All right!”

Just then, Claudia’s husband, Ken, wandered into the barn. “I was wondering where the hell everyone was.” We all just looked at him. “What’s going on?” he asked.

Claudia said, “We just saved Hannah’s life.”

He laughed, uncertainly. “What?”

As the explanations proceeded, Megan tied up the loose ends of her emergency call—removing the speculum from the cow’s mouth and dropping it in a pail of water; taking out the cannula, disinfecting the wound, dressing it; finally, writing up a lengthy, monstrous bill for her services.

“Don’t ever feed whole apples to cows,” she said, handing me the bill.

“I know. It’s too expensive.”

As she bent over to gather up her equipment, her cellphone slipped out of her breast pocket and fell with a ploop into the bucket of water.

“Uh-oh,” I said.

She just fished the phone out of the pail and shook the water off. “Oh, well. Hell of a way to end the day.”

Hannah swayed there in her stanchion, groggy, clueless, while Don fed her some hay.

That cow never did calve. But she was delicious.

__________________________________

Images

Belle and Hannah, used by permission of Willie McElroy.

Surly Belle by the author.

Aurochs at Lascaux by Prof saxx, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Belle and Henry, used by permission of Drew Conroy.

Newborn calf in caul by the author.