by David J. Lobina

I must say that, for someone who is a sort-of linguist and typically pays attention to the latest linguistic customs, I was quite surprised by the recent, sudden transformation of Kiev into Kyiv in the English-speaking media. Now, I’m not as obsessive about all things language as some of my fellow linguists, who seem to be able to notice every detail and nuance in the way language is used today everywhere they go – on posters in the underground, in the media, by eavesdropping on people’s conversations, etc. (TimeOut used to publish a section called Overheard in London, and I’m sure some of my friends followed it religiously) – but I have been following the Russo-Ukrainian War, as Wikipedia calls it, to some extent since Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, and even more so since Russia’s invasion of mainland Ukraine in February 2022 (236 days and counting, as I start this piece), and whilst I am sure that I was already aware of the use of the word ‘Kyiv’ to refer to the capital of Ukraine, I have nevertheless been taken aback by the fact that it has now become nearly universal in the English-speaking press to use the word ‘Kyiv’ instead of ‘Kiev’, even though employing the latter had been the norm for decades before current events.[1]

I especially mention “the English-speaking media” because the situation is rather different in other languages; this is clearly the case in the publications I follow in Italian and Spanish, where the use of the word ‘Kiev’ remains by far the most common, if not in fact as universal in these languages as ‘Kyiv’ has now become in English.

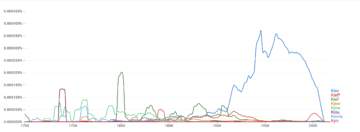

These impressions are confirmed by some of the data available from the Google Ngram Viewer, a search engine that returns the frequencies (that is, number of occurrences) of any string of words in the printed sources Google has collected over the years, up to 2019 (frequencies are calculated in terms of n-grams, and various languages are available). Thus, for English, and taking into consideration a greater variety of names for the Ukrainian capital that is usually the case, the Viewer returns the following chart for the 1700-2019 period:

As the graphic indicates, ‘Kiow’ and ‘Kiou’ seemed to be the most common terms in the 18th century, while ‘Kief’ was the most popular word at the turn of the 19th century, was still common towards the end of the century, and at the turn of the 20th was in competition, so to speak, with ‘Kieff’ and ‘Kiev’, the latter by far the most common form in the 20th century. As a small sample of these instances, Google Books returns a mention of ‘Kiou’ from a 1815 publication (The New Monthly Magazine), the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) lists an early use of ‘Kiev’ in a 1883 book by one WR Morfill called Slavonic Literature (where Kiev is described as a sacred place for Russians, incidentally), whilst an issue of the Dallas Morning News from 1938 actually uses ‘Kieff’.

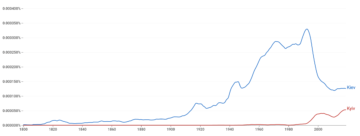

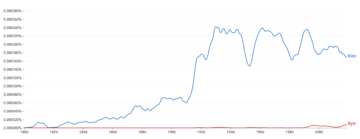

The sudden appearance of ‘Kyiv’ around the 2000s is clearly a novelty – the OED’s first record of the word in English comes from 2017 – and a direct comparison between the more common ‘Kiev’ with the newcomer ‘Kyiv’, laid out in the chart below, clearly shows that, even though the increased frequency of ‘Kyiv’ is a very recent phenomenon, accompanied by the (possibly related) relative decline of ‘Kiev’ in the last decade or so, by 2019 the word ‘Kiev’ was still more frequent.[2]

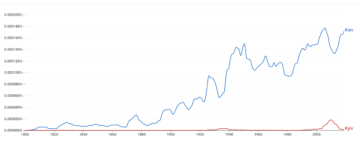

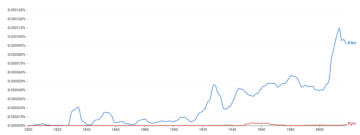

The situation is very different in Italian and Spanish; the two charts below show that ‘Kiev’ remains the most dominant form and there is no indication at all that ‘Kyiv’ will come close to replacing it in common usage any time soon (the situation is similar in French and German).[3]

What explains the difference? An online campaign targeting the English-speaking media is part of the story, as it happens. Started by the Ukrainian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 2018 – thus, around 4 years after Russia had annexed Crimea, in the middle of what is known as the War in Donbass, and around 4 years before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – the KyivNotKiev campaign, part of a wider undertaking to have some current English words for Ukrainian cities renamed (the so-called #CorrectUA initiative), was established to persuade English-speaking media and organisations to use the word ‘Kyiv’ for the Ukrainian capital instead of ‘Kiev’, the reason for this proposed change the apparent fact that the word ‘Kiev’ is derived from Russian Киев, whilst the Ukrainian name for the city is Київ, and a transliteration of the latter would be the most appropriate toponym in English – and, mutatis mutandis, for every other city from Ukraine, naturally: Odesa instead of Odessa, Kharkiv for Kharkov, Chornobyl for Chernobyl, e così via.

One could quibble about what the correct transliterations and pronunciations are here, an issue that is not very straightforward and remains unsettled in linguistics; ‘Kiyev’ is probably a better transliteration for Киев than ‘Kiev’, and ‘Kyjiv’ a more accurate transliteration for Київ than ‘Kyiv’, and in both cases the proposed pronunciations in English can only approximate the phonetic distinctions Russian and Ukrainian exhibit in the original (and, in the case of Kyiv/Kyjiv, the proposed pronunciation is that favoured by the state, and not necessarily the most common one).[4] But this is beside the point here, and so is, as a matter of fact, what the origin of the English word for the city of Kiev/Kyiv actually turns out to be.

There’s always been some distance in the world’s languages between endonyms – the native names for geographical places – and exonyms – the non-native names for these places. In particular, how exonyms become established in any language is the result of various factors, most of which are accidental, even serendipitous, but in every case it is a process long in the making, and mostly linguistic and social in nature. As such, the outcome is usually a norm that comes about not via diktat or mandate, but through usage and custom; or to quote a well-known passage from Horace’s De Arte Poetica on this issue:[5]

‘if it be the will of custom, in the power of whose judgement is the law and the standard of language’

This was certainly the case for the establishment of ‘Kiev’ as the main exonym for the city of Kiev/Kyiv in English, Spanish, Italian, etc. In the last two centuries or so, a variety of words were actually available to refer to the Ukrainian capital, as I showed to be the case for English above, and in the end ‘Kiev’ simply won out. But there was no mandate, no order or decree from the top down that ‘Kiev’ be officially used everywhere and by everyone, and certainly not from any foreign government or organisation.[6]

In the typical case, a language takes the most common word in usage in a given place – the actual sound, to be more accurate – and adapts it to its own orthography and phonology, but there’s plenty of uncertainty along the way, especially if some of these processes started a few hundred years ago, as is the case for Kiev/Kyiv.[7] For most of the last two hundred years, there was no universal, common endonym for the city of Kiev/Kyiv, in either Russian or Ukrainian, as there were various candidates around, and the same was consequently true for English, as we have seen. Even today the term Київ and its proposed transliteration of ‘Kyiv’ are both based on a particular take on what Standard Ukrainian ought to be, a position that is not without its problems.

In any case, the fact that English ‘Kiev’ is a transliteration of a Russian word – that it came from the Russian language, that is – really is neither here nor there. The Ukrainian Foreign Ministry makes much of the “russification” of Ukraine during the times of the Russian Empire (roughly, the 1721-1919 period) and the Soviet Union (roughly, the 1922-1991 period), but this is a very tendentious view of history, typical of the nationalist worldview, in fact, and in the event it should carry little weight as to which word should the English language, or any other language, for that matter, adopt to refer to Kiev/Kyiv.

As I argued in my series on Language and Nationalism here at 3QD Tower, the linguistic and cultural policies associated to terms such as russification – in this case, the imposition of the Russian language and culture upon a people – were only possible very recently in history: once state institutions were such that printing and universal and compulsory education was a reality, which in the case of Russia and Ukraine only really took place in the 20th century properly. Prior to that, there would have been a great variety of languages and cultures in both Russia and Ukraine, over and above the languages the elites spoke, the latter the varieties that eventually became what we now call the Russian and Ukrainian languages, but which in the last two hundred or so years would have been in the process of becoming the established languages of state institutions. Naturally, these elites would have hardly reflected the larger societies of either Russia or Ukraine then, though in time their language and culture were to be imposed upon these populations via the educational system, the usual way a national identity comes about (for details, revisit my posts!).[8]

In fact, and as I explained in the aforementioned series, very often standard or official languages become dominant vis-à-vis another standard, elite language because of greater prestige and influence (the reasons for this vary), and not necessarily because of any specific policies, repressive or otherwise, which in the past, especially in the 18th and 19th centuries, were either non-existent altogether or entirely ineffectual. There is certainly a fair amount of anachronism and presentism in the line taken by the Ukrainian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, but this is certainly in line with the view that theirs are political and nationalist arguments and have little to do with language or culture per se, let alone linguistics (Ukrainian nationalism is a “peripheral nationalism” of the kind I discussed here, to be contrasted with the core kind that Russian nationalism is).

Nevertheless, and to come back to linguistics, there is no presumption in linguistic practice, nor is it a feature of how languages actually change in history, for proper names such as city names to be derived from what may be regarded by some as the right source – from, that is, whatever may be seen as the native language of the place being named and referred to in a foreign language.[9] The list of words that have been adapted from intermediary languages, call them that, rather than from the languages of origin for this or that word is quite simply too extensive to list; it is also too common a situation to merit much attention.

Variety is the key concept here, which is also true of the fact that oftentimes proper names are not translated to begin with. As a small sample, Spanish Londres comes from the French Londres rather than directly from the English (from Old English Lunden, in fact); ‘Munich’ is not translated in English or Spanish, but it is in Italian (viz., Monaco), this usually following from the frequency of use in each case; once upon a time the proper name Karl, as in Karl Marx, was always translated as Carlos, in Spanish, and Carlo, in Italian, and this is not the case anymore, the reasons for this unclear; and the list can be extended indefinitely.

As mentioned, what’s going on here has little to do with language or linguistics. The change of Kiev into Kyiv is a political matter, which is not unrelated to the trend of city name changes that English is currently undergoing, the latter not a phenomenon that is taking place on account of any natural, unbiased change in the way English-speaking people talk about things, but the result of political campaigning and some misguided accommodations that English-speaking organisations (and people, no doubt) are conceding to foreign governments and organisations regarding how non-English cities and countries ought to be referred to, and in some cases even pronounced, in English.

The target of the CorrectUA campaign, after all, is the English language, the proper “world language”, and the only language that really counts politically. The Ukraine Foreign Ministry seemingly doesn’t care one bit what Ukrainian cities are called in Spanish or Italian, the historical and linguistic arguments offered to English-speaking organisations to convince them to use the preferred terms of the Ministry entirely absent in other languages.[10]

This has mirrored similar situations around the world. The Republic of Turkey has recently stated that it desires to be known as Türkiye at the United Nations (and elsewhere, apparently), as the country is named in the Turkish language, diacritic and all, and properly pronounced to boot. Burma changed its name to Myanmar in 1989, and likewise for Beijing in place of Peking, and in these two cases, as in many others, English-speaking media, and English-speaking people in general, have followed suit and changed custom (worth noting, however, that someone from Myanmar is a Burmese). And, again, this has not been the case in languages such as Italian and Spanish, where Burma and Peking remain the most common exonyms for these places (Birmania in both Italian and Spanish for Burma; Pechino in Italian, and Pekín in Spanish, for Peking). What explains these differences?

In part, this is due to two factors: (a) the alluded tendency of the English-speaking world to accommodate the demands of foreign governments and organisations regarding how certain names should be pronounced, not in the native languages of these governments, but in English, combined with (b) the confusing, and confused, muddying of political and linguistic arguments so common in the writings of those who approve, nay, demand such accommodations.[11] This has often resulted in rather uncomfortable bedfellows.

That Beijing should be referred to as ‘Beijing’ in English and not ‘Peking’ is hardly the wish of the Chinese people, or the population of Beijing, but of the ruling Chinese Community Party, an authoritarian regime with very little concern for human and civil rights. The change from Burma to Myanmar was engineered by a military junta that consistently turns a blind eye to human rights violations, some of which it may be directly instigating, and has little to with decolonisation processes, as sometimes claimed (the once-sainted Aung San Suu Kyi, for instance, never agreed with the change, though this did not seem to have an effect on the English-speaking world). And then there is the recent case of Türkiye, not a policy that has emanated from the Turkish people, but from their government, led by one Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who has overseen a rule marked by authoritarianism, corruption, and censorship. This is but a small sample, but there are more around, and in many cases English-speaking media and individuals find themselves in quite a precarious position, basically condoning name changes that come with vested political interests, and often from governments that are hardly democratic if not outright authoritarian.[12]

The case of Kiev/Kyiv and other Ukrainian cities may be regarded as being rather different at the present moment, given Russian aggression and the justness of Ukraine’s defence of its sovereignty. But why would any language have to change its own traditional way of referring to cities and countries, barring obvious offence, on the view that to do so, and to do so in a way that mirrors how such cities and countries are referred to in the “right” language of origin, somehow asserts the independence and sovereignty of any one country? To believe so is to conflate political positionings with normal linguistic practice, and furthermore to countenance diktats and mandates that are quite unwarranted.

Any one country obviously has the right to call itself whatever it wants in its own language, and to be known as what it wishes to be known in official bodies such as the UN,[13] but the expectation that it also ought to be able to prescribe how other languages refer to its name, or to the names of some of its cities, is a different matter altogether. There is nothing but a slippery slope down this route: it is one thing to discuss and describe how a city name is pronounced, or can be pronounced, in the local language, but it is another thing entirely to prescribe how it ought to be pronounced according to the official, standard language, and how it ought to be written and pronounced in other languages. Turkey really has no business prescribing how it should be referred to in English – and neither does Ukraine.

Languages have always had different ways to refer to the same things, from apples and oranges to proper names, and a change of endonym doesn’t necessarily entail that the corresponding exonym should also change, especially if this turns out to be little more than a nationalist gesture. It shouldn’t be necessary to point out that calling the capital of Ukraine ‘Kiev’ in English, Italian or Spanish does not make the city of Kiev/Kyiv any less Ukrainian (with the provisos mentioned here), and God forbid that anyone will want to argue that non-English-speaking countries are not showing the appropriate level of support for Ukraine because their media and speakers keeping talking about ‘Kiev’.

I personally don’t mind using ‘Kyiv’ at all, though in my idiolect ‘Kiev’ is pretty well established and this will remain the case in my Italian and Spanish selves, as it remains the custom in these languages, but I certainly reject any mandates or diktats as to what the correct form is, especially when such arguments are incredibly tendentious and the actual question at heart is a moot point anyway, as I have tried to show here.[14]

[1] I will aim to capitalise the words ‘Kiev’ and ‘Kyiv’ throughout this post, not only when referring to the city itself, but also when referring to the words themselves; in the latter case, I will typically write them within single quotations marks, as I have just done and is the norm in linguistics, though I might not follow this rule very strictly (I hope that the context will clarify the usage in each case, though).

[2] I imagine that by now this trend must look different, though it is worth pointing out that a 2019 article from Euronews reports that ‘Kiev’ was still a common toponym in the city of Kiev/Kyiv itself, possibly on account of how widely spoken Russian is in Ukraine; as I will broach later on, both in the main text and in the endnotes, the toponym ‘Kyiv’ is not as well established as it is claimed to be.

[3] Thus, for French:

German uses the word ‘Kiew’ for the most part, though ‘Kyjiw’, the German version of ‘Kyiv’, has made an appearance (see here and here from Duden, the standard dictionary of High German).

[4] As a case in point, the surname of the current president of Ukraine appears transliterated as Zelenskyy, Zelensky or Zelenskiy, depending on the source (in this case, Wikipedia, the BBC, and The Guardian, respectively).

[5] See here for some commentary on this point.

[6] In most cases, there wouldn’t have been any institution to issue such a decree to begin with, let alone to enforce it. One may well wonder about the role of Royal Societies and the like in these matters, especially the kind of Language Academies that the French and the Spanish have had for a long time. However, there is a tendency to exaggerate how much influence these Academies actually have in how language is used, which would have been very limited indeed in early modern European history anyway, especially before printing and universal education had become a reality towards the end of the 19th century and the early 20th century. In more recent times, however, most Spanish media instantly update their style manuals if The Royal Spanish Academy introduces some changes as to how certain words are to be written – in 2010, for instance, the Academy stipulated that some words would be losing their diacritics, and the vast majority of the media followed suit – though it is unclear how widespread the changes are outside of official bodies and the media. This offers an interesting parallel to the Kiev/Kyiv case; just as it is now possible for the Ukrainian Foreign Ministry to lobby English-speaking media to change their ways, and be successful about it, this would not have been an easy undertaking a hundred years ago.

[7] Of course, Ukrainian and Russian names introduce the further complication that these languages employ a different alphabet and thus the words must be transliterated, but the point I am making is that it is the actual sound that is adapted into a foreign language, and then written/transliterated.

[8] In the case of Russian elites, they would have mostly spoken a form of Russian, whereas Ukrainian elites would have spoken versions of both Russian and Ukrainian, given the influence of Russian culture there and elsewhere, a situation that remains the case in Ukraine today.

[9] In reality, there is no matter of fact regarding what some may define as the rightful, native language or culture of the region we now call Ukraine. All nations, and national identities, are abstract and artificial, certainly constructed from the top down, and, as stressed, a recent phenomenon in history. This is as true of Ukraine as it is of Russia (and elsewhere); in the particular case of Ukraine, the country remains, to this day, a rather diverse place, where the languages and cultures of Ukrainians and Russians both have a strong presence (see this piece as a case in point), much as is the case in many other regions of the world in which there is a peripheral nationalism in competition with a greater, more dominant, nationalism (here I discussed the case of Catalonia, another diverse region, despite the claims to the contrary; my discussion there may offer interesting parallels here). Russification has certainly been a reality in Ukraine in the past, and in eastern Ukraine more clearly in recent decades, but it would be disingenuous to deny that there is any counterpart to russification in Ukraine today; “ukrainification” is also a reality, and here too it is a case of imposing a particular language and culture upon a population. Such processes are simply part and parcel of what is involved in creating a nation, and a national identity – it really is intrinsic to the nationalist outlook to aim for homogeneity and be exclusionary.

[10] I have already stated that the historical reasons adduced by the Foreign Ministry are rather tendentious when it comes to the supposed russification of Ukraine during the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union (the latter taken to be entirely Russia-centric, it seems), and the linguistic arguments are equally weak, if not entirely mistaken. The CorrectUA site carries on about ‘outdated, Soviet-era’ monikers, as if words like ‘Kiev’ had not become established in English before the Russian revolution (this piece in The Guardian simply takes this claim for granted, and the arguments then offered – e.g., that we should get our language right, and change to ‘Kyiv’ – simply don’t follow); the site also claims that referring to Ukraine as ‘the Ukraine’, the latter an obsolete phrasing now anyway, is a way to deny Ukrainian sovereignty and furthermore suggests that Ukraine is a region and not a country, which is nonsense, given that plenty of countries start with the article ‘the’ in their names (The Netherlands, The Bahamas, etc.; this piece from the BBC amusingly quotes the Ukraine embassy in London in 2012 stating that the ‘the Ukraine’ phrase is ‘both grammatically and politically’ incorrect).

[11] A particularly depressing example of such confused argumentation can be found here, where keeping to established exonyms is judged to be a case of outmoded thinking in cases such as Burma.

[12] The Turkish case is much more recent, but I have already seen one blogger use the word ‘Türkiye’ to refer to Turkey as if this were entirely normal and proper (I certainly winced).

[13] Maybe; the working languages at the UN are French and English, but country names usually appear in English only: Italy and Spain are known as, well, Italy and Spain at the UN, and not as Italia and España, and it need hardly be mentioned that Italia, España, and Türkiye are not English words.

[14] The good folk at Language Log have discussed some of these issues in various posts (here, here, and here), and both the entries and the comments are worth reading. There is plenty of discussion of decolonisation processes in those posts, and the comments by one Bob Ladd are particularly interesting, though I find this take slightly exaggerated.