by David Introcaso

Arguably the greatest global health policy failure has been the US Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) refusal to promulgate any regulations to first mitigate and then eliminate the healthcare industry’s significant carbon footprint.

Arguably the greatest global health policy failure has been the US Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) refusal to promulgate any regulations to first mitigate and then eliminate the healthcare industry’s significant carbon footprint.

With US healthcare spending projected to equal $4.9 trillion this year, HHS is effectively responsible for regulating more than half of the $9 trillion global healthcare market. Because of its size as well as infamous fragmentation and waste, US healthcare’s estimated 553 million metric tons of annual greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions account for approximately 25% of global healthcare GHGs. If it was its own state, US healthcare would easily rank within the top 10% of the highest GHG polluting countries.

The health harms associated with GHG emissions and an equal amount of air pollution constitute an immense public health crisis and pose the greatest threat to patient safety. These harms are innumerable and unrelenting and impact everyone, everywhere, always. Presently, they are largely defined as toxic air pollution resulting from fossil fuel combustion, climate-charged extreme weather events and vector borne diseases.

Per the World Health Organization (WHO), 99% of the world’s population is exposed to PM2.5, or fine particulate matter, 2.5 microns in diameter or less, substantially the result of fossil fuel combustion. As the world’s leading environmental health risk, the effect is over eight million global deaths annually. Children are disproportionally victimized because they breathe more air per kilogram of body weight, breathe more polluted air being closer to the ground and have undeveloped lungs, brains and immune systems. For seniors, a recent study published in British Medical Journal concluded that no safe threshold exists for the chronic effect of PM2.5 on their overall cardiovascular health.

Per the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), for the five year period ending in 2022 the average cost of billion-dollar climate-charged disaster events, that include drought, flooding, extreme heat, hurricanes, tornados and wildfires, equaled $119 billion, triple the average annual cost since 1980. Read more »

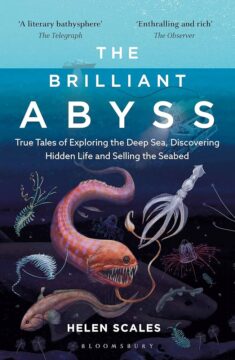

Marine biologist Helen Scales’ previous book The Brilliant Abyss: True Tales of Exploring the Deep Sea, Discovering Hidden Life and Selling the Seabed, brilliantly provided us with a glimpse of the wondrous life forms that inhabit the abyss, the deep sea. She also made known her profound concern for the future of ocean life posed by human activity. She now expands on those issues and concerns in her new book, What The Wild Seas Can Be: The Future of the World’s Seas. Scales provides us with a fascinating exposition of the pre-historic ocean and the devastating impact of the Anthropocene on ocean life over the last fifty years. Her main concern, however, is the future of the ocean and her new book makes a major contribution to people’s understanding of the repercussions of human activity on ocean life and the measures that need to be taken to protect and secure a better future for the ocean.

Marine biologist Helen Scales’ previous book The Brilliant Abyss: True Tales of Exploring the Deep Sea, Discovering Hidden Life and Selling the Seabed, brilliantly provided us with a glimpse of the wondrous life forms that inhabit the abyss, the deep sea. She also made known her profound concern for the future of ocean life posed by human activity. She now expands on those issues and concerns in her new book, What The Wild Seas Can Be: The Future of the World’s Seas. Scales provides us with a fascinating exposition of the pre-historic ocean and the devastating impact of the Anthropocene on ocean life over the last fifty years. Her main concern, however, is the future of the ocean and her new book makes a major contribution to people’s understanding of the repercussions of human activity on ocean life and the measures that need to be taken to protect and secure a better future for the ocean.

In this conversation—excerpted from the Aga Khan Award for Architecture’s upcoming volume, Beyond Ruins: Reimagining Modernism (ArchiTangle, 2024) set to be published this Fall, and focusing on the renovation of the Niemeyer Guest House by East Architecture Studio in Tripoli, Lebanon—

In this conversation—excerpted from the Aga Khan Award for Architecture’s upcoming volume, Beyond Ruins: Reimagining Modernism (ArchiTangle, 2024) set to be published this Fall, and focusing on the renovation of the Niemeyer Guest House by East Architecture Studio in Tripoli, Lebanon—

Michael Wang. Holoflora, 2024

Michael Wang. Holoflora, 2024 In the game of chess, some of the greats will concede their most valuable pieces for a superior position on the board. In a 1994 game against the grandmaster Vladimir Kramnik, Gary Kasparov sacrificed his queen early in the game with a move that made no sense to a middling chess player like me. But a few moves later Kasparov won control of the center board and marched his pieces into an unstoppable array. Despite some desperate work to evade Kasparov’s scheme, Kramnik’s king was isolated and then trapped into checkmate by a rook and a knight.

In the game of chess, some of the greats will concede their most valuable pieces for a superior position on the board. In a 1994 game against the grandmaster Vladimir Kramnik, Gary Kasparov sacrificed his queen early in the game with a move that made no sense to a middling chess player like me. But a few moves later Kasparov won control of the center board and marched his pieces into an unstoppable array. Despite some desperate work to evade Kasparov’s scheme, Kramnik’s king was isolated and then trapped into checkmate by a rook and a knight.

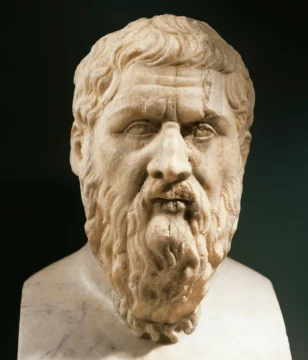

In Discourse on the Method, philosopher René Descartes reflects on the nature of mind. He identifies what he takes to be a unique feature of human beings— in each case, the presence of a rational soul in union with a material body. In particular, he points to the human ability to think—a characteristic that sets the species apart from mere “automata, or moving machines fabricated by human industry.” Machines, he argues, can execute tasks with precision, but their motions do not come about as a result of intellect. Nearly four-hundred years before the rise of large language computational models, Descartes raised the question of how we should think of the distinction between human thought and behavior performed by machines. This is a question that continues to perplex people today, and as a species we rarely employ consistent standards when thinking about it.

In Discourse on the Method, philosopher René Descartes reflects on the nature of mind. He identifies what he takes to be a unique feature of human beings— in each case, the presence of a rational soul in union with a material body. In particular, he points to the human ability to think—a characteristic that sets the species apart from mere “automata, or moving machines fabricated by human industry.” Machines, he argues, can execute tasks with precision, but their motions do not come about as a result of intellect. Nearly four-hundred years before the rise of large language computational models, Descartes raised the question of how we should think of the distinction between human thought and behavior performed by machines. This is a question that continues to perplex people today, and as a species we rarely employ consistent standards when thinking about it. The human tendency to anthropomorphize AI may seem innocuous, but it has serious consequences for users and for society more generally. Many people are responding to the

The human tendency to anthropomorphize AI may seem innocuous, but it has serious consequences for users and for society more generally. Many people are responding to the

I’ve been surfing for about three years.

I’ve been surfing for about three years.  Sughra Raza. After The Rain. Vermont, July 2024.

Sughra Raza. After The Rain. Vermont, July 2024.