by Paul Braterman

Michael Gove (remember him?), when England's Secretary of State for Education, told teachers

Michael Gove (remember him?), when England's Secretary of State for Education, told teachers

“What [students] need is a rooting in the basic scientific principles, Newton's Laws of thermodynamics and Boyle's law.”

Never have I seen so many major errors expressed in Newton via Wikipedia in so few words. But the wise learn from everyone, [1] so let us see what we can learn here from Gove.

From the top: Newton's laws. Gove most probably meant Newton's Laws of Motion, but he may also have been thinking of Newton's Law (note singular) of Gravity. It was by combining all four of these that Newton explained the hitherto mysterious phenomena of lunar and planetary motion, and related these to the motion of falling bodies on Earth; an intellectual achievement not equalled until Einstein's General Theory of Relativity.

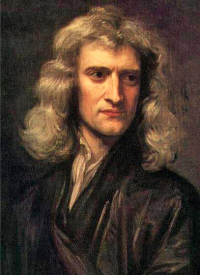

Above, L, Isaac Newton, 1689. Below, R, Michael Gove, 2013

In Newton's physics, the laws of motion are three in number:

In Newton's physics, the laws of motion are three in number:

1) If no force is acting on it, a body will carry on moving at the same speed in a straight line.

2) If a force is acting on it, the body will undergo acceleration, according to the equation

Force = mass x acceleration

3) Action and reaction are equal and opposite

So what does all this mean? In particular, what do scientists mean by “acceleration”? Acceleration is rate of change of velocity. Velocity is not quite the same thing as speed; it is speed in a particular direction. So the First Law just says that if there's no force, there'll be no acceleration, no change in velocity, and the body will carry on moving in the same direction at the same speed. And, very importantly, if a body changes direction, that is a kind of acceleration, even if it keeps on going at the same speed. For example, if something is going round in circles, there must be a force (sometimes, confusingly, called centrifugal force) that keeps it accelerating inwards, and stops it from going straight off at a tangent.

Then what about the heavenly bodies, which travel in curves, pretty close to circles although Kepler's more accurate measurement had already shown by Newton's time that the curves are actually ellipses? The moon, for example. The moon goes round the Earth, without flying off at a tangent. So the Earth must be exerting a force on the moon.

Read more »