by R. Passov

As the clouds of WWII darkened Austria, Kurt Gödel, the greatest  logician of modern times, at Einstein’s urging, brought his two magnificent proofs to Princeton. There he would remain for almost forty years, never mentoring a graduate student, rarely lecturing, adding only one substantial but incomplete proof to the cannon of math.

logician of modern times, at Einstein’s urging, brought his two magnificent proofs to Princeton. There he would remain for almost forty years, never mentoring a graduate student, rarely lecturing, adding only one substantial but incomplete proof to the cannon of math.

Mildly underwhelmed by the impact of his discoveries, at Princeton he would gradually set aside math in favor of philosophy. Little of this work was published in his lifetime. But it was enjoyed by Einstein who for the last decade of his life, walked alongside as Gödel discussed a field Einstein once likened to ‘writings in honey.’

________________________________________

Gödel was born in 1906, into a German speaking family living in Brunn (Brno) Moravia, then part of the Austria-Hungary Empire, soon to be annexed by Germany, now part of the Czeck Republic. His father before passing unexpectedly in 1929, had built a successful textile business that would secure his family’s finances.

An early childhood struggle with Rheumatic fever left Gödel forever suspicious of the state of his health. He took his primary education at the local Realgymnasium. Modeled after the enlightened German system, the gymnasium offered “mental gymnastics, developing both mind and body.” Following his older brother, in 1921 he entered the University of Vienna.

Easily establishing his gifts, he studied theoretical physics, enjoyed the life of a student and earned a reputation for sleeping late. Read more »

The authority of scientific experts is in decline. This is unfortunate since experts – by definition – are those with the best understanding of how the world works, what is likely to happen next, and how we can change that for the best. Human civilisation depends upon an intellectual division of labour for our continued prosperity, and also to head off existential problems like epidemics and climate change. The fewer people believe scientists’ pronouncements, the more danger we are all in.

The authority of scientific experts is in decline. This is unfortunate since experts – by definition – are those with the best understanding of how the world works, what is likely to happen next, and how we can change that for the best. Human civilisation depends upon an intellectual division of labour for our continued prosperity, and also to head off existential problems like epidemics and climate change. The fewer people believe scientists’ pronouncements, the more danger we are all in.

Growing up, a lighter branded you as suspect to any Baptist worth his King James Version. Because really, other than smoking and setting houses on fire to incinerate the family within just for kicks, what did you need a lighter for anyway? If you wanted to light something righteous like a candle or the water heater, you reached for the box of safety matches next to the paprika in the spice cabinet. They had SAFETY written on the box in case you felt tempted to go astray. Lighters should have had Iniquity Equipment inscribed on them as far as we were concerned.

Growing up, a lighter branded you as suspect to any Baptist worth his King James Version. Because really, other than smoking and setting houses on fire to incinerate the family within just for kicks, what did you need a lighter for anyway? If you wanted to light something righteous like a candle or the water heater, you reached for the box of safety matches next to the paprika in the spice cabinet. They had SAFETY written on the box in case you felt tempted to go astray. Lighters should have had Iniquity Equipment inscribed on them as far as we were concerned.

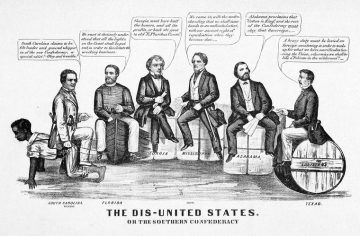

By the time Sherman’s armies had scorched and bow-tied their way to the sea, by the time Halleck had followed Grant’s orders to “eat out Virginia clean and clear as far as they go, so that crows flying over it for the balance of the season will have to carry their own provender with them,” and by the time Winfield Scott’s Anaconda Plan was finished squeezing every drop of life out of the Confederacy, there had to be those who wondered what possible logic would lead intelligent men like Jefferson Davis to make such a catastrophic choice.

By the time Sherman’s armies had scorched and bow-tied their way to the sea, by the time Halleck had followed Grant’s orders to “eat out Virginia clean and clear as far as they go, so that crows flying over it for the balance of the season will have to carry their own provender with them,” and by the time Winfield Scott’s Anaconda Plan was finished squeezing every drop of life out of the Confederacy, there had to be those who wondered what possible logic would lead intelligent men like Jefferson Davis to make such a catastrophic choice.

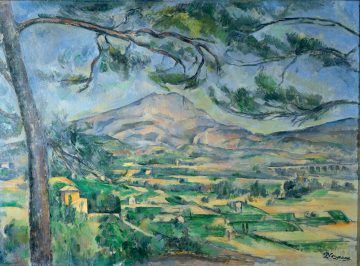

Philosophers have spilled a great deal of ink attempting to nail down once and for all the necessary and sufficient conditions for a thing’s being a work of art. Many theories have been proposed, which can seem in retrospect to have been motivated by particular works or movements in the history of art: if you’re into Cézanne, you might think art is “significant form,” but if you’re impressed by Andy Warhol, you might that arthood is not inherent in a work’s perceptible attributes, but is instead something conferred upon it by members of the artworld.

Philosophers have spilled a great deal of ink attempting to nail down once and for all the necessary and sufficient conditions for a thing’s being a work of art. Many theories have been proposed, which can seem in retrospect to have been motivated by particular works or movements in the history of art: if you’re into Cézanne, you might think art is “significant form,” but if you’re impressed by Andy Warhol, you might that arthood is not inherent in a work’s perceptible attributes, but is instead something conferred upon it by members of the artworld.

logician of modern times, at Einstein’s urging, brought his two magnificent proofs to Princeton. There he would remain for almost forty years, never mentoring a graduate student, rarely lecturing, adding only one substantial but incomplete proof to the cannon of math.

logician of modern times, at Einstein’s urging, brought his two magnificent proofs to Princeton. There he would remain for almost forty years, never mentoring a graduate student, rarely lecturing, adding only one substantial but incomplete proof to the cannon of math.

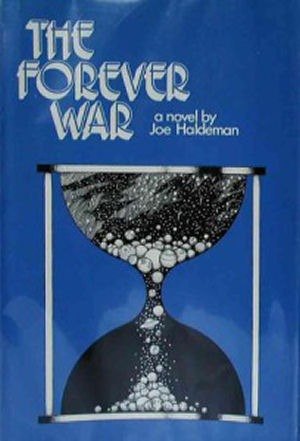

In 1974, noted science fiction author Joe Haldeman published a novel called The Forever War, which won several awards and spawned sequels, a comic version, and even a board game. The Forever War tells the story of William Mandella, a young physics student drafted into a war that humans are waging against an alien race called the Taurans. The Taurans are thousands of light years away, and traveling there and back at light speed leads Mandella and other soldiers to experience time differently. During two years of battle, decades pass by on Earth. Consequently, the world Mandella returns to each time is increasingly different and foreign to him. He eventually finds his home planet’s culture unrecognizable; even English has changed to the point that he can no longer understand it.

In 1974, noted science fiction author Joe Haldeman published a novel called The Forever War, which won several awards and spawned sequels, a comic version, and even a board game. The Forever War tells the story of William Mandella, a young physics student drafted into a war that humans are waging against an alien race called the Taurans. The Taurans are thousands of light years away, and traveling there and back at light speed leads Mandella and other soldiers to experience time differently. During two years of battle, decades pass by on Earth. Consequently, the world Mandella returns to each time is increasingly different and foreign to him. He eventually finds his home planet’s culture unrecognizable; even English has changed to the point that he can no longer understand it.