by Robert Fay

During the annus horribilis of 1968 when it became clear the U.S. would never “win” in Vietnam, John Wayne decided to star and direct in a propaganda film called The Green Berets. Wayne was a die-hard Orange County anti-communist who believed that the U.S. military was winning on the battlefield in South Vietnam, but losing in the media and public relations realm.

Rather shrewdly, Wayne centered his film on the U.S. Army Special Forces, a.k.a. the Green Berets, whose small 12-man A-Teams lived and trained with the anti-communist Montagnards, the indigenous peoples of Vietnam’s remote central highlands. The Green Berets in the 1960s were an all-volunteer, highly-selective outfit with both mystique and a bit of holdover, Kennedy-era glamour. These teams spoke the local languages and formed close and often lifelong bonds with their Montagnard peers. This mission profile remains to this day the classic Special Forces game; make contact with local populations and then fight alongside them against a common enemy.

If John Wayne had depicted the typical American military units in Vietnam, main-line U.S. Army or U.S. Marine Corps infantry troops trudging through rice fields—even with all the hilarious puffery of Hollywood special effects—he’d have had far-less glamour to work with. These units were often filled with draftees who went out on company-sized operations supported by massive amounts of artillery and air support, some of it indiscriminately unleashed upon the countryside. There were generally no Vietnamese speakers among the troops, and the cultural and historical knowledge (e.g., of the recent Indochina War between the Vietnamese and the French) was nil. Read more »

r a train and someone passed through begging for change. I’ve lived in New York City long enough that I don’t just start taking my wallet out and going through it in crowded public spaces, but beyond that, I don’t have change. I normally don’t carry cash. If I have cash on me its for one of two reasons, either someone has paid me back for something in cash (which in these days of Venmo is increasingly unlikely) or I have a hair or nail appointment where they like their tips in cash. So even if I have cash, it’s bigger bills and certainly no coins. And I’m sure I’m not unusual. I pay for things with credit cards. I pay other people using Apple Pay or Venmo. I mentioned this thought to someone who told me that they had seen someone begging in New York with details of their Venmo account. On the one hand, there seems to be a certain chutzpah to that, after all, if you have a bank account to receive the money in and some kind of smart phone to access it, is your situation as dire as you’re making out? On the other hand, it’s pretty smart. Of course, there are serious privacy issues involved in giving money to a random stranger through an app like Venmo, it’s not private, so I probably wouldn’t do that either, but it’s an interesting idea, if it could be made more anonymous and secure. Apparently, at least in China,

r a train and someone passed through begging for change. I’ve lived in New York City long enough that I don’t just start taking my wallet out and going through it in crowded public spaces, but beyond that, I don’t have change. I normally don’t carry cash. If I have cash on me its for one of two reasons, either someone has paid me back for something in cash (which in these days of Venmo is increasingly unlikely) or I have a hair or nail appointment where they like their tips in cash. So even if I have cash, it’s bigger bills and certainly no coins. And I’m sure I’m not unusual. I pay for things with credit cards. I pay other people using Apple Pay or Venmo. I mentioned this thought to someone who told me that they had seen someone begging in New York with details of their Venmo account. On the one hand, there seems to be a certain chutzpah to that, after all, if you have a bank account to receive the money in and some kind of smart phone to access it, is your situation as dire as you’re making out? On the other hand, it’s pretty smart. Of course, there are serious privacy issues involved in giving money to a random stranger through an app like Venmo, it’s not private, so I probably wouldn’t do that either, but it’s an interesting idea, if it could be made more anonymous and secure. Apparently, at least in China,

It has been a little over a week since the redacted Mueller Report was released, and so many words have been spilled that there could be a drought by summer if the umbrage reservoirs are not refilled. Can we just retire the word “closure”?

It has been a little over a week since the redacted Mueller Report was released, and so many words have been spilled that there could be a drought by summer if the umbrage reservoirs are not refilled. Can we just retire the word “closure”?

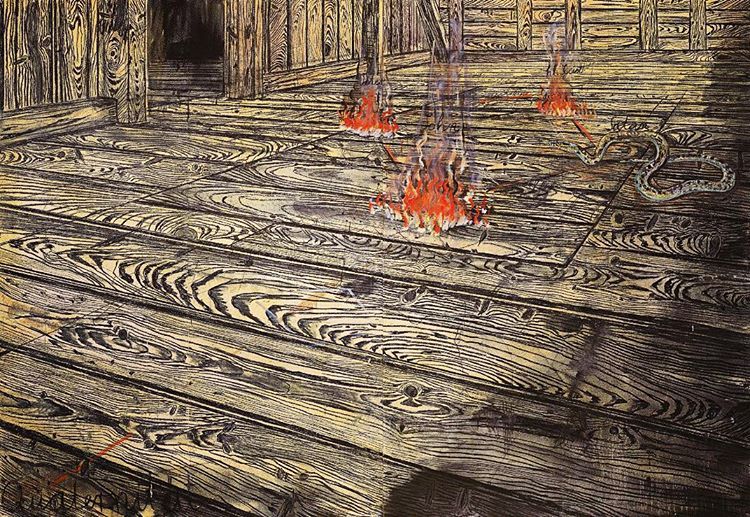

The attic of Notre Dame cathedral, with its tangled, centuries-old dark wooden beams, was affectionately known as the ‘forest’. The fire that originated up there last week made me think of an early Anselm Kiefer painting Quaternity, (1973), three small fires burning on the floor of a wooden attic and a snake writhing toward them, vestiges of the artist’s Catholic upbringing in the form of the Father, the Son, the Holy Ghost and the Devil. Metaphor meets reality in the sacred attics of stored mythologies.

The attic of Notre Dame cathedral, with its tangled, centuries-old dark wooden beams, was affectionately known as the ‘forest’. The fire that originated up there last week made me think of an early Anselm Kiefer painting Quaternity, (1973), three small fires burning on the floor of a wooden attic and a snake writhing toward them, vestiges of the artist’s Catholic upbringing in the form of the Father, the Son, the Holy Ghost and the Devil. Metaphor meets reality in the sacred attics of stored mythologies.

Last time

Last time It’s rather like changing fonts. Not many would say a change of font will make a parking ticket sting less (although Comic Sans might make it sting more). As endless internet discussions rage about the meaning and content of the Mueller report, altogether too few dissect Robert Mueller’s choice of fonts [1].

It’s rather like changing fonts. Not many would say a change of font will make a parking ticket sting less (although Comic Sans might make it sting more). As endless internet discussions rage about the meaning and content of the Mueller report, altogether too few dissect Robert Mueller’s choice of fonts [1]. A brief scan across global politics generates concerns as to what is actually going on in the politics of many states. Authoritarian regimes have always been with us, and will probably be with us for some time to come. Of greater concern is the emergence of political leaders in liberal democracies who espouse a politics which resonates with the past: a politics of nationalism, and nativism, and the inward-looking thinking that is associated with those ideologies. This trend, in what I would call a ‘regressive politics’, is in opposition to the process of globalisation.

A brief scan across global politics generates concerns as to what is actually going on in the politics of many states. Authoritarian regimes have always been with us, and will probably be with us for some time to come. Of greater concern is the emergence of political leaders in liberal democracies who espouse a politics which resonates with the past: a politics of nationalism, and nativism, and the inward-looking thinking that is associated with those ideologies. This trend, in what I would call a ‘regressive politics’, is in opposition to the process of globalisation.

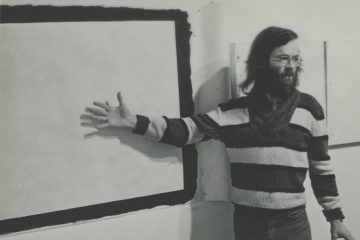

Tony Conrad’s retrospective of objects produced for galleries or institutions, titled Introducing Tony Conrad, is currently on view at the ICA Philadelphia. “Introducing” because so many people are still unfamiliar with his work. His works were predicated on both the amount of time they took to make and the patience that they required of their audience, which no doubt contributed to his lack of popularity. Conrad, the prodigal Harvard grad, spent his career working through aesthetic problems like an eccentric scientist. This can be gathered from his exhaustive lectures, teaching, and writings on sound and film. Formally, however, the works often look like a child made them. Not in a cynical way denoting lack of care, but in an earnestly amateur approach to object making. Because the works are less concerned with looking skillfully produced and more concerned with what a durational existence might impart onto things, the audience is left with big-picture questions like, what does it mean for an artwork to still be in progress after the artist’s death?

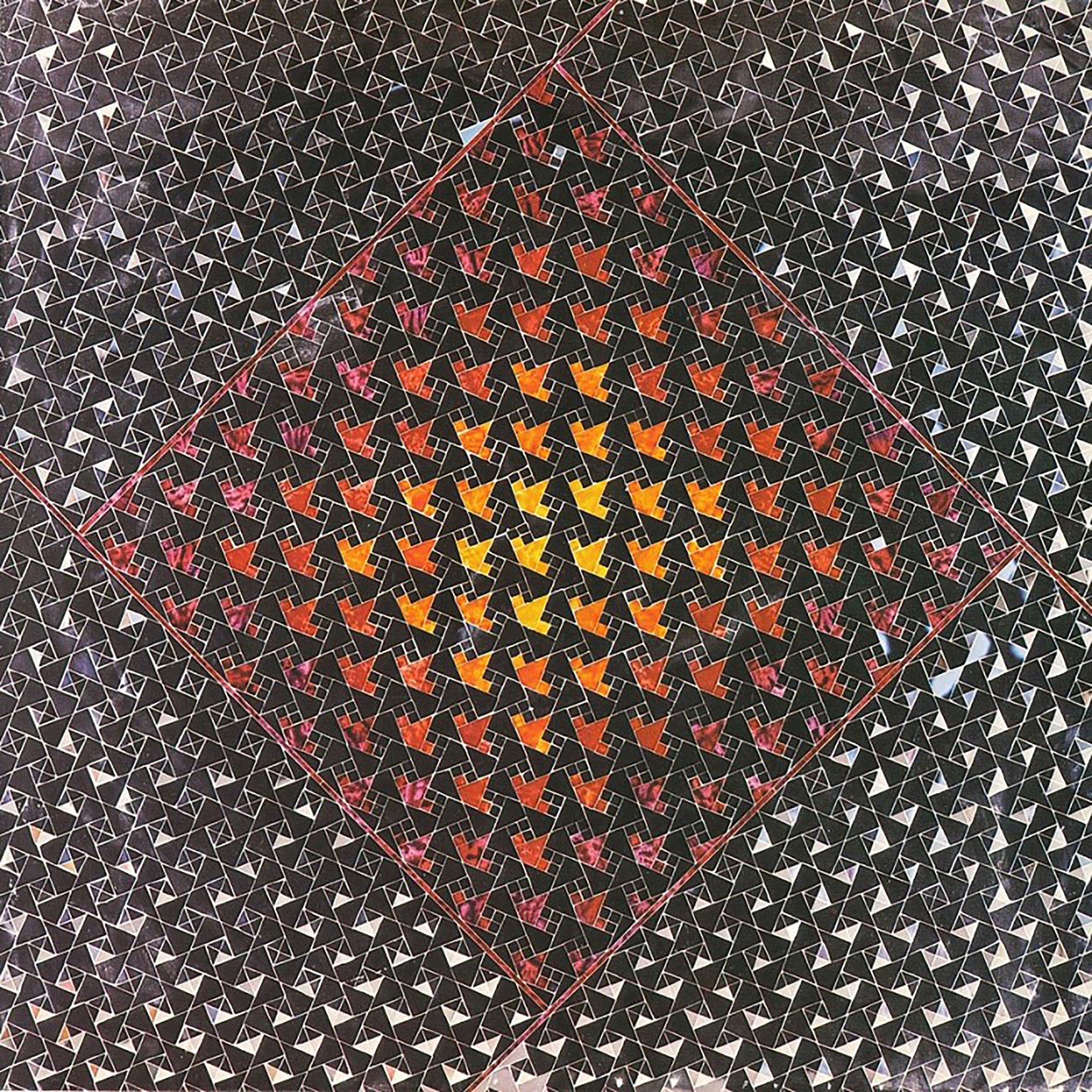

Tony Conrad’s retrospective of objects produced for galleries or institutions, titled Introducing Tony Conrad, is currently on view at the ICA Philadelphia. “Introducing” because so many people are still unfamiliar with his work. His works were predicated on both the amount of time they took to make and the patience that they required of their audience, which no doubt contributed to his lack of popularity. Conrad, the prodigal Harvard grad, spent his career working through aesthetic problems like an eccentric scientist. This can be gathered from his exhaustive lectures, teaching, and writings on sound and film. Formally, however, the works often look like a child made them. Not in a cynical way denoting lack of care, but in an earnestly amateur approach to object making. Because the works are less concerned with looking skillfully produced and more concerned with what a durational existence might impart onto things, the audience is left with big-picture questions like, what does it mean for an artwork to still be in progress after the artist’s death? This is best captured in Conrad’s most well-known artworks, the “infinite duration” Yellow Movies, which were painted yellow squares on paper. The idea was that they would darken and yellow with age over the course of their lifespan, thus constituting an ever-changing work, or “movie” (and for Conrad, the longest durational movie ever, putting Warhol’s Empire (1964) to shame). These works and others in the show capture his fascination with time and what it entails. The objects on view in the retrospective are largely the byproducts of experiments. Conrad, an accomplished experimental musician and filmmaker known for his vexing compositions, took his cue from thorough research into a topic, investigating the variety of forms it could take. For instance, one of the first things visitors see are a selection of handmade instruments using unorthodox materials, like a guitar made from a child’s racquet, or violin affixed to a stationary scrap-wood apparatus. Another instance is Conrad’s pickled film, which he shot and then cured in a vinegar solution in Ball jars, riffing on how film is developed in an alchemical solution.

This is best captured in Conrad’s most well-known artworks, the “infinite duration” Yellow Movies, which were painted yellow squares on paper. The idea was that they would darken and yellow with age over the course of their lifespan, thus constituting an ever-changing work, or “movie” (and for Conrad, the longest durational movie ever, putting Warhol’s Empire (1964) to shame). These works and others in the show capture his fascination with time and what it entails. The objects on view in the retrospective are largely the byproducts of experiments. Conrad, an accomplished experimental musician and filmmaker known for his vexing compositions, took his cue from thorough research into a topic, investigating the variety of forms it could take. For instance, one of the first things visitors see are a selection of handmade instruments using unorthodox materials, like a guitar made from a child’s racquet, or violin affixed to a stationary scrap-wood apparatus. Another instance is Conrad’s pickled film, which he shot and then cured in a vinegar solution in Ball jars, riffing on how film is developed in an alchemical solution.  Robert Caro might well go down in history as the greatest American biographer of all time. Through two monumental biographies, one of Robert Moses – perhaps the most powerful man in New York City’s history – and the other an epic multivolume treatment of the life and times of Lyndon Johnson – perhaps the president who wielded the greatest political power of any in American history – Caro has illuminated what power and especially political power is all about, and the lengths men will go to acquire and hold on to it. Part deep psychological profiles, part grand portraits of their times, Caro has made the men and the places and times indelible. His treatment of individuals, while as complete as any that can be found, is in some sense only a lens through which one understands the world at large, but because he is such an uncontested master of his trade, he makes the man indistinguishable from the time and place, so that understanding Robert Moses through “The Power Broker” effectively means understanding New York City in the first half of the 20th century, and understanding Lyndon Johnson through “The Years of Lyndon Johnson” effectively means understanding America in the mid 20th century.

Robert Caro might well go down in history as the greatest American biographer of all time. Through two monumental biographies, one of Robert Moses – perhaps the most powerful man in New York City’s history – and the other an epic multivolume treatment of the life and times of Lyndon Johnson – perhaps the president who wielded the greatest political power of any in American history – Caro has illuminated what power and especially political power is all about, and the lengths men will go to acquire and hold on to it. Part deep psychological profiles, part grand portraits of their times, Caro has made the men and the places and times indelible. His treatment of individuals, while as complete as any that can be found, is in some sense only a lens through which one understands the world at large, but because he is such an uncontested master of his trade, he makes the man indistinguishable from the time and place, so that understanding Robert Moses through “The Power Broker” effectively means understanding New York City in the first half of the 20th century, and understanding Lyndon Johnson through “The Years of Lyndon Johnson” effectively means understanding America in the mid 20th century.