by Emrys Westacott

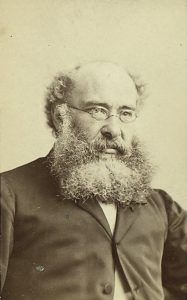

What do 21st century American college faculty and 19th century Church of England Clergyman have in common? A surprising amount. This is one reason I would heartily recommend the novels of Trollope, Austen, and others to my colleagues in academia.

What do 21st century American college faculty and 19th century Church of England Clergyman have in common? A surprising amount. This is one reason I would heartily recommend the novels of Trollope, Austen, and others to my colleagues in academia.

Clerics are interesting figures in a number of 19th century novels. Sometimes they are portrayed sympathetically, as is Henry Tilney in Northanger Abbey; often, though, they are ridiculed, either gently, like Bishop Proudie in Barchester Towers, or scathingly, like Mr. Collins in Pride and Prejudice. But what should draw rueful smiles of recognition from academics today is not the personality types represented but their situations within a complicated, hierarchical system that dispenses enviable benefits to some and chronic frustration to others.

Extrapolating from such novels with a little imaginative license, we can form the following picture. At the beginning of the 19th century, the Church of England had about 11,500 “livings”–positions tied to particular parishes. These typically came with a house (the vicarage, the rectory), and an income, often quite modest. Such livings were usually dispensed by individuals or institutions that were major landowners in the parish. They provided life-long security and social respectability.

Under the primogeniture system of inheritance, the eldest son inherited the bulk of his father’s estate. This meant that younger sons of the gentry had to pursue some profession, and the respectable options for those who viewed trade as rather sordid were few: the military, the law, medicine, or the church. One of the important functions of the Church of England at that time was thus to provide socially acceptable employment to educated middle and upper-middle class men who lacked independent means.

Unfortunately, there were many more educated young men seeking positions in the church than there were “livings.” Supply exceeded demand. As late as 1830, about fifty percent of Oxbridge undergraduates intended to enter the church. Recently minted Ph.D.s seeking tenure-track positions will have no trouble relating to their situation.

Aspirant English clerics usually had a classical education at Oxford or Cambridge. They would know Latin, and be versed in theology, able to participate in arcane disputes on the correct interpretation of scripture or the proper rituals of worship. Some might do so with great zeal, convinced that the future of Christendom hung on how one read a particular passage in Corinthians, or at least that their own professional future hung on whether their partisan zeal was noticed and approved of by certain influential personages.

Ideally, the initial motive for studying theology and taking holy orders was to follow a calling to do God’s work. In practice, though, such lofty ideals, if they ever were present, often gave way to the pressing and decidedly down-to-earth concern with making a living–or, more precisely, with securing a “living.” In this matter, connections were what mattered. A newly ordained graduate’s best hope of obtaining a living would be through the patronage of someone responsible for filling such a position: a bishop, the master of a college, or a member of the landowning gentry.

The lucky ones got a living. The less lucky worked as curates, assisting a parish priest–sometimes more than one, since their stipend was usually quite meagre–very often without housing; they served a sort of apprenticeship with the understanding, or at least the hope, that this would lead to a living. Newly minted Ph.D.s today, working as adjunct faculty, scurrying between two or three institutions, paid at a lower rate than regular faculty and without benefits, waiting and hoping for a tenure-track position to open up, should have no trouble relating to their situation.

Yet the lucky ones who landed a living didn’t necessarily think of themselves as lucky. Some, to be sure, might settle down contentedly in a rural parish, enjoy a respectable position in the community, socialize pleasantly with others of a similar social standing, and take up butterfly collecting, or keep a nature diary. But others would find it hard to shrug off a lingering discontentment. They felt disappointed and frustrated on two counts.

First, there was the disconnect between what they were educated to do and what they actually did. Their study of ancient languages, theology, philosophy, and church history equipped them admirably to participate with sophistication and insight in learned discussions relating to religion. But their job was basically to provide pastoral care to layity who couldn’t give a hang about theology. Latin and theology were essentially useless when it came to helping people cope with life’s problems, organizing community activities, or running a church. To be sure, they composed sermons that incorporated some of their learning; but they suspected that even those parishioners who bothered to show up didn’t always listen too attentively, particularly the ones who tended to snore while asleep. (Most college lecturers know the feeling: hence the definition of a professor as “someone talks during someone else’s sleep.”)

There was also, of course, their ritual functions. Dressed in their vestments, they led the congregation in prayer, officiated at weddings, christened babies, intoned at funerals, performed communion, blessed things that needed blessing, and so on. But none of this required erudition. Anyone able to read could perform the same tasks, except for the requirement that such tasks be performed by an ordained priest, since he alone was invested with the requisite authority. In other words, what mattered here was not so much actual learning as the possession of a qualification taken to signify learning. The donning of academic regalia by faculty at graduation ceremonies carries a somewhat similar meaning: it legitimizes the ceremony and the diplomas granted by displaying the authority the faculty possess in virtue of their qualifications.

The other source of discontentment lay in the hierarchical character of the church along with an unfortunate tendency of people situated in hierarchies to compare themselves to those who stand above them in terms of status, wealth, power, or recognition. So while, from the perspective of an impoverished curate still hoping for a secure benefice, a country vicar had it pretty good, some vicars would find it hard not to avoid lusting in their hearts after the larger houses, fatter incomes, greater prestige, and superior connections, enjoyed by vicars of more prosperous parishes, deans, archdeacons, and bishops. But once you had buried your light under a bushel in Little Podunkton, it could be hard to move up the ladder. Providing good pastoral care was a fine thing; but promotion came more readily to those who were well-connected and in a position to make the right sort of impression on the right kind of people.

The correspondences between of all of this and contemporary academia, at least in the US, are not hard to discern. The initial subject-oriented zeal of the young graduate student; the growing concern for making a living once financial aid runs out (multiplied in proportion to the number of offspring one is responsible for); the anxieties of the “job market,” especially pronounced in fields where there seem to be few respectable alternatives to academia; the golden ring of the tenure-track job; the exhausting, poorly remunerated reality for many graduates of temporary positions and adjunct labour; the hierarchy of institutions and the potential of this to induce a low-grade form of dissatisfaction even among those who can count themselves lucky (i.e. the 21.5 percent and shrinking of all faculty who in 2014 held tenured positions).

For people teaching at less selective colleges, though, whether tenured or not, the most striking similarity is perhaps the discrepancy between the level of expertise required to obtain a doctorate and what is actually needed in order to teach the general education courses that constitute much of the workload. On the one hand, doctoral research is expected to lead to publications in professional journals; on the other hand, many of the undergraduates currently attending the 3000 plus four-year colleges in the US are virtually innumerate, have astoundingly poor general knowledge, and struggle to write a grammatically well-formed sentence.

How and why this situation has come about is a complicated story. Happily, though, the situation of those hoping to work in academia today is better than that of aspiring clergyman, whether in the nineteenth century or now. In modernized countries like Britain, church attendance and religious belief has persistently declined over the past two centuries, and with it the need for priests. There is no reason to suppose this trend will be reversed. The demand for educated college graduates, by contrast, is robust. So although the working conditions of college teachers may worsen as administrators embrace the savings offered by the gig economy, the need for instructors is likely to remain high. Small comfort perhaps, but better than the alternative.