by Evan Edwards

When my partner and I were expecting our first child, I remained obstinately distant from all parenting books. I had adapted, and taken to heart, Rainer Rilke’s advice to Franz Kappus about avoiding introductions to great works of art, and reckoning that, in the poet’s words, “such things are either partisan views, petrified and grown senseless in their lifeless induration, or they are clever quibblings in which today one view wins and tomorrow the opposite.” Rilke’s point seems to be that introductions do more to obscure our ability to reach the work of art than elucidate it. Since a child is, among other things, a living, breathing work of art, it took very little for me to translate the great poet’s advice to the work of child-rearing. Surely no book would truly help me approach a task as infinitely arduous and dizzyingly beautiful as bringing a human being into the world.

When my partner and I were expecting our first child, I remained obstinately distant from all parenting books. I had adapted, and taken to heart, Rainer Rilke’s advice to Franz Kappus about avoiding introductions to great works of art, and reckoning that, in the poet’s words, “such things are either partisan views, petrified and grown senseless in their lifeless induration, or they are clever quibblings in which today one view wins and tomorrow the opposite.” Rilke’s point seems to be that introductions do more to obscure our ability to reach the work of art than elucidate it. Since a child is, among other things, a living, breathing work of art, it took very little for me to translate the great poet’s advice to the work of child-rearing. Surely no book would truly help me approach a task as infinitely arduous and dizzyingly beautiful as bringing a human being into the world.

But my embargo on introductions to being a parent stopped short on one question: how do I raise a child in an age of accelerating mass extinction? And how best to teach them to care for the world, for nature? How do I talk to my child about the end of the world? While other issues in raising children often prompt answers that are simply as idiosyncratic as the authors pumping out these tracts, the question of how to raise a child who is not simply environmentally tuned, but tuned to a global ecosystem whose new overarching rule is rapid and often unpalatable change is one that any conscious parent will recognize as being largely outside the purview of the instinct for care folded into our biological and cultural DNA.

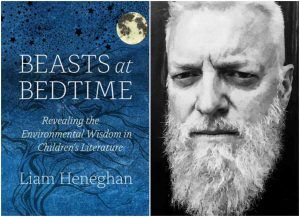

A good amount of thought has been put into this problem, explicitly starting with Richard Louv’s 2005 diagnosis of “nature-deficit disorder” in (mostly American) children of the time. Louv found that the rise of a “culture of fear” in parents, and the increasing influence of the emerging Web 2.0 were the main culprits for the children of the aughts’ disconnection from ‘nature.’ Since then, organizations like the No Child Left Outside Coalition and authors like Scott Sampson (in How to Raise a Wild Child) represent a growing chorus of voices that are aimed at getting children to spend more time outdoors. I know I need these books, and to hear these conversations, because I grew up in the 90s and early 2000s, and thus was part of the first generation of individuals bearing this diagnosis. This is, in part, why I decided to lift the parenting book embargo. One last note: although critics have pointed out that this “condition” is not new, it is probably right to say that before now, it was present in trace amounts, or steadily increasing amounts, until it got so bad (during my childhood) that it was finally diagnosed as lethal. The way that steadily increasing your daily arsenic intake can only keep you safe until it doesn’t. Liam Heneghan’s Beasts at Bedtime is partly in this tradition, but approaches it from an entirely different angle.

It is a deeply personal book, written by a father in the years following the departure of his youngest son from the proverbial nest. The anecdote that opens the book is, perhaps not coincidentally, an anecdote about the time his oldest son Fiacha “became a bird” when he was three years old. Heneghan tells us that the book is “written for the parents, teachers, librarians, and guardians of children who may think they are birds,” as well as other animals. So, while it is not a ‘parenting book,’ per se, it is a book for parents. (Well not just parents, or even just for those who work with children, but I’ll get to that). Parenting books tell us parents stories about how we ought to be and act with relation to our children, while children’s stories tell them about the world they’ve entered, through myth. Beasts at Bedtime is a book that tells us about who we are; those of us that tell our children these stories as a way of shaping their experience; those of us that were, perhaps, shaped by them as well. It is a book about parenting, and thus in some sense a “parenting book,” because it shows us how to draw out the ecological shading of these stories in the conversations we have with children (and indeed, with ourselves) about them. As such, it retains the dubious distinction of being the only parent book I have ever read all the way through.

When I have glanced through popular parenting books, what I’m overwhelmed by is the amount of information I’m presented with. Information, I mean, in the abstract sense. They give us information that presents itself in an objective way, as if it weren’t shaped by the kind of worldviews and research methods that the authors had employed. That is, it’s information that is, as philosopher Timothy Morton puts it, “designed to look like…they are not designed.” Beasts at Bedtime does not rely on an information dump like many parent’s books because is not particularly concerned with data. Heneghan is clear to state his position and methods in the introduction, but beyond this, the book does its work by showing us, that is by attuning us, to the information (i.e. “the environmental wisdom in Children’s Literature”) that it presents.

Again, Beasts is not particularly concerned with data. That is, with the exception of its continual reference to the frequency and density of certain words in themes in both texts and bodies of work. In his reading of both the Grimm brothers and Hans Anderson fairy tales, for example, Heneghan tells us about the relative frequency of words and themes like “hunger and thirst,” “urban settings,” “woods,” and so on. In chapter nine, on Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, Heneghan reminds us that the story is largely occupied by the wild party in which Max boogies with the beasts, and illustrates this point by noting that the book is “almost 18 percent rumpus.” He also often draws our attention to all of the animals, plants, and other non-human actors that populate both stories and the illustrations that accompany them. He points out, in chapter twenty-four, that in an illustration accompanying The Story of Babar, there is a surprising amount of biodiversity, and proves it by giving the population of the picture in a quarter-page list.

But this isn’t a mere data dump. Heneghan refers us to the “Shannon diversity index” in chapter nine. This index measures the health of an ecosystem by capturing “the diversity and evenness [and richness] of creatures in a biological diversity.” Heneghan’s propensity for giving us the stats on the populations of certain words and concepts in these texts, on my reading, is analogous to the kind of information that the Shannon index communicates. All of these stats, lists, and data points serve to demonstrate what seems to be the underlying point of the book as a whole: children’s literature is already richly populated by ecology and by ecological wisdom. The “six bird species…daisies, several grass species, reeds…tree species…shrubs…butterflies, ladybugs, ground beetles, a wasp, dragonflies and one snail” in Babar are no less important for a full description of the countryside than the eponymous pachyderm and automobile. After checking out The Story of Babar from my local library, and studying the illustration described in the previous paragraph, I sat outside and was immediately aware of the bugs, birds, plants, and human-produced objects that were, of course, always already there.

My son had seen these elements of the picture as we read through it. Or maybe he didn’t. Or what is more likely, we both saw them, and didn’t bother with their presence because of their apparent irrelevance to the narrative we thought we were being told. One way of reading Beasts is that it performs exactly what ecology has been telling us for the last two centuries: the thin narrative told by humans about how they engage with the rest of creation is just one thread in a broader story—or perhaps more accurately, the broader stories—of non-human life. This broader story is one where we have to reckon with the flows of energy and matter that our anthropocentric narratives carry along with them like whirls of water around a boat gliding in a pond. Elsewhere in his reading of Babar, Heneghan reminds us that since “an elephant turd…weighs up to 5 pounds,” “if Babar’s stay with the Old Lady lasted [just] a full year, the household would have had to deal with in excess of 36 tons of Babar’s excrement.” In this, and in all of the readings that deal with the relation between urban and wild landscapes (and everything in between), Heneghan shows us that the question of where resources come from, and how they are allocated—a decidedly ecological dimension of life to be sure—is, if not central to the story, at least present in varying degrees in great works of children’s literature.

The book is divided into seven sections. Each approaches a text, or a collection of them, by resituating their narratives into these wider accounts of humanity’s relation to the rest of the world. The first section, on pastoral tales, sets the tone for the book. In it, Heneghan draws our attention to the liminal space between “rural” (or ‘wild) and “urban” (or ‘civilized’) settings. “The Pastoral” occurs in tales about gardens (in, for example, Beatrix Potter’s Peter Rabbit), cultivated forests (as in Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh), and in the fields (as in what Heneghan says is among his favorite pastoral tale, “The Prodigal Son”). These stories tell us that there are some things in nature that are violent (Mr. McGregor’s pursuit of poor Peter), sad, and difficult, but that everything is (more or less) resolved in the end. “They lived happily ever after,” and so forth. Along the way, Heneghan introduces the lives of the authors, as well as the rich undercurrents of ecological wisdom, scientific understanding, and folk knowledge of nature that underwrite their often fairly simple stories. This is a mark of the pastoral, Heneghan reminds us, that in them are “visions of peaceful and harmonious times in rustic settings,” which promise “a life of simplicity, outside in nature, under clement skies.” The Pastoral is then, in many ways, the way we often tend to think of a life that is environmentally tuned.

But, of course, things are not always so simple. Sometimes our encounter with nature is wild, threatening, or simply weird—as in the case of the bizarre plot twists that Heneghan calls our attention to in his chapter on the tales of the Brothers Grimm. Section two, on wilderness tales, turns our focus to the forays that children take beyond the hearth in these books. In what is perhaps the most wide ranging chapter, both in breadth of reference and depth of thought, Heneghan plumbs the psychological experience of encountering the wild. He turns his gaze from Maurice Sendak’s terse (“338 words”) masterpiece, Where the Wild Things Are, to the cave paintings of Chauvet, France, and finally to a curious meeting of art history and evolutionary biology to illuminate the aesthetic composition—that is, the feel—of our idea of both the wild and wilderness. Elsewhere in the section, as one among many who grew up within the mythology of the Lord of the Rings, two chapters on Tolkien’s universe provide a welcome opportunity to reflect on the various ways that its creatures dwell, and the effect that landscape had on Tolkien’s sensibilities.

The next chapter, on island stories, begins by reminding us that all wild places are islands, metaphorically speaking. What we find so ecologically endearing about wilderness is that in it we imagine a place that is remote, otherworldly, and, as it were, separated from us and from ‘culture.’ This section introduces us to the importance that the study of islands has had on scientific and philosophical reflection; Darwin’s time in the Galapagos and Rousseau’s reading of Robinson Crusoe get places of privilege. What Heneghan shows, particularly through his short, but effective reading of Golding’s Lord of the Flies, is that our ideas of complete isolation—of being on a literal island, or on a ‘wilderness island’ as in the case of books like Gary Paulsen’s Hatchet—are always intertwined with our ideas about culture, about humanity, and about civilization, and how the two sides bordering that liminal space referred to several paragraphs prior are inseparable.

Reflecting on wilderness and ‘islands’ requires that we turn back to the city, the epitome of civilization. This is a chapter that I read with great interest, as my fear of not doing enough to introduce my son to ‘real nature’ in the city is allayed here. In the chapter on Babar, as I mentioned before, we see that many of these stories afford us the possibility to see how ecological processes, non-human life, and the city are deeply bound to one another. Heneghan shows us how to have conversations with our children about nature in the city because he points us to stories that show how it is with us in the concrete already. This is, ultimately, among the greatest virtues of the book. Rather than telling us how to talk to each other (and by extension, to children) about the ways that we can rebuild our relations to nature, Beasts shows us the ways that the first myths we hear—in the form of childhood stories—always already have those lessons in them. And if we were raised on these stories as well, then it shows us that they have already shaped our ecological sense in deep ways.

This is why I say that it is a book for parents and those who regularly interact with children, but that it is also for those who perhaps don’t even like children. The analyses in Beasts point us to the spaces of common reference where we can talk about what it is like to be enmeshed in a world, especially one that is in the midst of a geologically and biologically—that is to say, planetarily—significant change. Reflecting on the stories of our juvenile canon (and Heneghan’s way of reading can be extended to newer, or less known, or non-canon, or ‘foreign’ children’s literature, and not just those stories treated in the book) allows us to see the things that we already know about nature, but perhaps forgot in the trauma of growing up.

The final thematic section, on “learning to care,” takes up the question I posed at the start of this review: how do I talk to my child, or to myself, or to others, about the collective experience of living through a mass extinction? The section takes Antoine de Saint-Exupery’s The Little Prince and Theodor Geisel’s The Lorax as case studies in ways of caring. Heneghan draws our attention to the way that the Lorax speaks to the Onceler, the contempt and impatience that he has. He uses this as a way of showing a problematic manner of communicating, a preachy method of inciting care that condescends as much as it fails. Saint-Exupery’s Prince, on the other hand, cares for his rose because of the lesson of a fox, which is to say, he learns from nature as much as we do from this book. These two models of care (one speaking—perhaps a little haughtily—“for” the trees, and the other caring simply because of the way that the rose is affected by his connection to it) give Heneghan the opportunity to think through not only how we might be better ecological beings, but how we can use bedtime to feel around the edges of the dream-like world of the anthropocene we now inhabit.