When I was a child back in the nuclear-anxiety-Cold-War 1950s I went to see a film called Godzilla, King of the Monsters. I probably noticed that the people on screen didn’t look like Americans. They looked – well, I don’t know what I would have called them then, but they were in fact Japanese, except for this reporter guy (Raymond Burr) who talked a lot. What I remember is being scared out of my wits by this HUGE monster that seemed determined to destroy the world.

When I was a child back in the nuclear-anxiety-Cold-War 1950s I went to see a film called Godzilla, King of the Monsters. I probably noticed that the people on screen didn’t look like Americans. They looked – well, I don’t know what I would have called them then, but they were in fact Japanese, except for this reporter guy (Raymond Burr) who talked a lot. What I remember is being scared out of my wits by this HUGE monster that seemed determined to destroy the world.

What I didn’t know at the time – I suppose that almost no one in the American audience did – is that this was somewhat different from the Japanese original, which came out in Japan in 1954 as Gojira. The Japanese original has two interlinked storylines: the story about the monster from the sea and a story about love vs. arranged marriage, which grapples with tradition vs. change. That second one was dropped from the American re-edit; the idea of an arranged marriage was and is all but meaningless in America, though it remains alive in Japan and in other nations. With a sense of grave ritual that is missing from the Americanized version, the Japanese original is a richer film.

* * * * *

Gojira, Ishiro Honda, dir. Toho Co, Ltd. 1954; reissued by Classic Media 2006.

On March 1, 1954, the United States detonated Castle Bravo at Bikini Atoll in the South Pacific. Castle Bravo was a hydrogen bomb with a yield of 15 megatons, roughly two or three times what had been expected. It was the largest radiological accident ever caused by the land of the free and the home of the brave and poisoned the crew of a Japanese tuna boat, the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (Lucky Dragon No. 5), with one crew member eventually dying of leukemia. This led to a tuna scare in Japan and a petition drive to ban the bomb.

Tomoyuki Tanaka was one of many Japanese who followed the story closely. He worked as a producer for Toho Company, Ltd., one of Japan’s major film studios. When a deal fell through and created a hole in the studio’s release schedule, Tanaka decided to fill it with a new kind of film, a sci-fi horror story filmed in noir style and featuring a prehistoric beast awakened by an atomic explosion. The beast was named Gojira and the film was released in Japan on November 3, 1954.

If you look closely, you’ll see a reference to Lucky Dragon No. 5 early in Gojira. The movie opens on a freighter at sea off Odo Island, the Eiko-Maru. It’s evening and some of the sailors are gathered together while one of them plays the guitar and another the harmonica. There’s a sudden bright light and a loud noise. The sailors rush to the side of the ship to see what’s happened:

Notice the number on the life preserver, “No. 5.” The freighter sinks and all hands are lost.

Thus begins Gojira. It builds slowly. Another ship is lost, meetings are held, decisions made, and eventually a scientific team is sent Odo Island to investigate. The team is headed by Dr. Kyouhei Yamane, a noted paleontologist, who is accompanied by his daughter Emiko and Hideto Ogata, who works for the steamship company that’s lost two boats. At long last, 21 minutes into a 98 minute film, we catch our first glimpse of Gojira:

Gojira’s footprints are saturated with Strontium 90, as is the Island’s well water, evidence that Gojira as been tainted by radiation from some otherwise unidentified nuclear test. Beyond that, we know and learn little about why Gojira’s on the rampage. It’s simply an ugly fact, the monster’s been awakened and is heading toward Tokyo, what do we do?

Not much that’s effective. Gojira arrives at night and wastes Tokyo. Here’s Gojira crushing a passenger car from a commuter train:

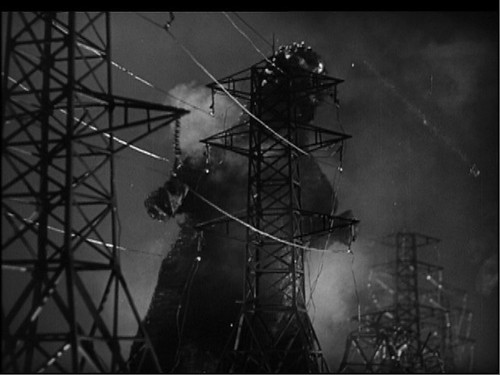

Gojira is unfazed by the high-voltage fence erected as a defense measure:

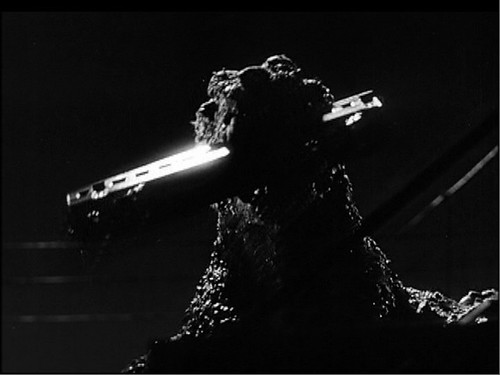

Here we see Gojira’s atomic breath and glowing dorsal plates:

A bird’s eye view:

“We’ll be joining your father in just a moment,” says a mother to her young children:

Now Gojira marches on the Diet building:

When the attack’s over, devastation:

Here we see children being checked for radiation:

Emiko comforts a little girl whose mother has just died:

And so it goes. Add in a final battle in which the good humans triumph over the evil monster, leaven with some romance, and you have your standard-issue creature feature.

But that’s not how Gojira works. There is a little romance, with a Japanese twist, and there’s more. First the romance.

We first see Emiko, the Professor’s daughter, and Ogata, a young official and diver with Southern Sea Steamship company, early in the film, just after the Eiko-Maru is lost. He’s just come out of the shower at his office and is toweling off while in slacks and an undershirt. He gets a phone call about the lost ship. Emiko enters the room while he’s still on the phone. When the call is over, he talks to her as he continues to dry himself:

He’s got to see about the lost ship and so, alas, must cancel their date for the evening.

These two are obviously a couple. As the film moves to Emiko’s father’s house, we see Ogata there as well, and quite comfortable. He’s obviously well known in the household and, in particular, Prof. Yamane knows him.

A half hour later in the film a reporter refers to one Dr. Daisuke Serizawa as Yamane’s future so-in-law. Whoa! Son-in-law? Where’d that come from?

One infers that, at some time in the past, Dr. Yamane arranged for Emiko and Daisuke to become betrothed and that’s their public status as these events unfold. But, as she explains to Ogata, she thinks of Serizawa as a much-admired older brother. Serizawa is certainly aware of Emiko’s attraction to Ogata, who is not at all comfortable with the situation. We never know or hear what Dr. Yamane thinks of the situation, but he must know that Emiko and Ogata are seeing one another. No one’s being sneaky and secretive.

So, we’ve got a problem, two men and one woman. But it’s not simply a conflict between the men. It’s also a conflict between traditional Japanese marriage custom, marriage by parental arrangement, and a new mode of marriage, by free choice of the members of a couple. When Ogata finally decides to broach matters with the Professor, the conversation goes awry. Instead, they talk about Gojira. The Professor wants Gojira to live so that he can be studied: how does he keep alive after his exposure to radiation? Ogata believes that Gojira must be killed for the good of the greater community. They quarrel and Ogata is kicked out of the house.

Now the monster plot and the marriage-romance plot have become intertwined. I leave it as an exercise for the psychoanalytically-minded to demonstrate that the two plots are, in fact, one and the same. As such they will be resolved together.

Dr. Serizawa is a young but distinguished, scientist. He’s discovered a horrible device that he calls the Oxygen Destroyer, the physics of which is deeply obscure. It’s quite capable of killing Gojira, but it’s also capable of being used as a doomsday device. For that reason Serizawa decides to keep his discovery secret. He knows that, if it is used against Gojira, the politicians will then force him to build another one to be used against humans. He reveals his secret to Emiko and swears her to secrecy.

Subsequently she is so horrified at the devastation of Tokyo that she reveals his secret to Ogata and the two confront him about using the Oxygen Destroyer against Gojira. Ogata and Serizawa get into a struggle and Ogata receives a small head wound. Serizawa is horrified at his behavior and, reluctantly, agrees to use the device. He starts burning his papers so that no one can find out the secret. Anyone with half a brain can see, at this point, that he’s decided to kill himself as the Oxygen Destroyer kills Gojira.

That’s exactly what happens. But . . . there’s more.

Children are a significant presence in the film. Five minutes into the film families of sailors from the lost ships (the Eiko-Maru was not the only ship Gojira attacked) have gathered at the steamship company to learn what happened; children are quite visible in the small crowd. We see children during evacuation and destruction scenes and in the hospital. And they play a critical role in convincing Serizawa to allow the use of his Oxygen Destroyer.

After the fight with Ogata, as Emiko is bandaging Ogata’s head wound, Serizawa turns to the television, where he sees and hears a choir of teenaged Japanese girls singing a hymn for peace. The hymn runs for two and a half minutes as we see shots of the physical devastation, people in hospitals, people gathered together in prayer, and, finally, the young girls singing:

It is when the hymn is over that Serizawa starts destroying his papers and announces that he will allow the device to be used.

The fact that this hymn runs for two-and-a-half minutes is important. During that time only one thing happens which advances the plot: Serizawa makes his decision. Honda, the director, could easily have allotted no more than 10, 20, 30 seconds to that one event and it wouldn’t have changed the blow-by-blow in any significant way. The effect of running that hymn for so long while recapping the carnage is that it changes the mood of the rest of the film. Gojira’s death will be staged as a solemn sacrifice, a mutual sacrifice between man (the death of Serizawa) and nature (the death of Gojira).

Honda began preparing for this ritualized ending roughly eleven minutes into the film, on the first trip to Odo Island. While we’re watching a ritual, an old man explains that, in the old days the islanders would sacrifice young girls to a sea monster named Gojira to keep him from coming out of the sea to eat the islanders. This new monster was named after that old legend. The ritual we’re now watching is all that’s left of those old customs:

Similarly, an hour later, there is a ritual solemnity in the way Serizawa burns his papers, putting them on the fire one at a time. The film cuts from a close-up of burning paper to a ship at sea sailing out to meet Gojira in his own territory. We hear march music on the soundtrack.

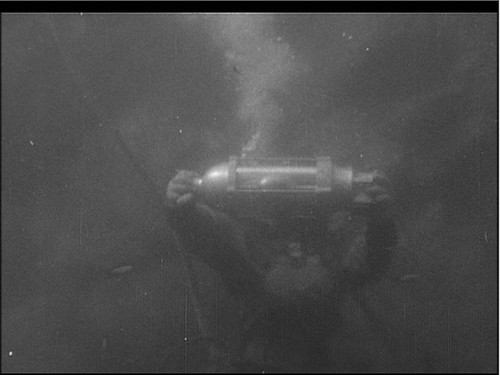

This music ends quickly and we’re on board the ship as a radio announcer delivers a running commentary on the day’s events. There is no music on the soundtrack. As Ogata and Serizawa descend into the sea, Emiko is playing out lines for one of them, but we don’t know which one. The camera follows them down and a slow instrumental dirge comes up on the sound track. The divers move slowly and come upon Gojira:

There is no violent confrontation between the men and Gojira. They all move slowly until the men are in position. Ogata comes to the surface while Serizawa in effect presents the Oxygen Destroyer to Gojira in a ritual gesture:

The device does its work; Gojira dies as Serizawa cuts his lines and remains with him. Serizawa’s speaks his last words through the intercom to Ogata, who is now at the surface: “Ogata, it worked! Both of you, be happy. Good-bye . . . farewell!” When it becomes evident that Serizawa too is gone, Yamane doff his cap to the man who can no longer be his son-in-law and utters his name, “Serizawa.” Gojira rises to the surface for a final death cry:

Gojira sinks to the bottom and dies, the flesh melting away and leaving nothing but the skeleton.

Ogata to Emiko: “He wanted us to be happy.” The youth choir comes up on the sound track.

Yamane: “I can’t believe that Gojira was the only surviving member of its species. But if we keep on conducting nuclear tests, it’s possible that another Gojira might appear. . . . somewhere in the world, again.”

There is a final salute, but to whom? Serizawa, Gojira?

* * * * *

When I decided to watch Gojira (aka Godzilla) I had few specific expectations. I expected cheesy special effects and was not disappointed. As Roger Ebert had noted:

In these days of flawless special effects, Godzilla and the city he destroys are equally crude. Godzilla at times looks uncannily like a man in a lizard suit, stomping on cardboard sets, as indeed he was, and did. Other scenes show him as a stuffed, awkward animatronic model. This was not state of the art even at the time; “King Kong” (1933) was much more convincing.

Nor was that Ebert’s only objection to the film. He thought much of the dialogue was poor, and has pronounced the film to be bad without reservation.

I cannot agree with that judgment. Ebert’s review misses too much, saying nothing about the marriage plotline. I suspect that Ebert read it as a fundamentally realistic story – one can almost believe that a monster such as Gojira does exist and could be aroused – and thus finds its flaws, the effects, the dialog, to be fatal. For all I know he might also have been puzzled at Prof. Yamane’s apparent obliviousness to his daughter’s relationship with Ogata, which I too find a bit troublesome.

But I don’t think we should read the film as fundamentally realistic with, however, some farfetched elements. As I have already indicated, it is a ritual. As such, the obvious monster costume does not matter, nor does the dialog, nor even Yamane’s obliviousness. In fact, those failings force us to attend more closely to how everything thing works together, to the pacing, the lighting, and the music. Akira Ifukube’s spare and elegant score plays a major role in the film, from Gojira’s theme to the dirges and, above all else, the hymn for peace.

Whatever expectations I had beyond the cheesy special effects, I was not expecting to be moved to tears by a hymn for peace sung by a youth choir. Being moved to tears is not in itself indicative of much; cheap sentiment will do the trick.

But I’m not willing to dismiss that particular segment – and others, as mere sentiment. The music itself was fitting: slow and stately, simple, and well performed. It was accompanied by imagery of the most serious sort, massive destruction of a great city and the suffering of its people. To put that music together with those images at that point in the film required artistry of a high order.

It is not clear to me how one weighs Gojira’s virtues with its limitations. The film is thus itself something of a monster; it defies easy categorization and quick judgment.

* * * * *

For more on Gojira see The Gojira Papers.