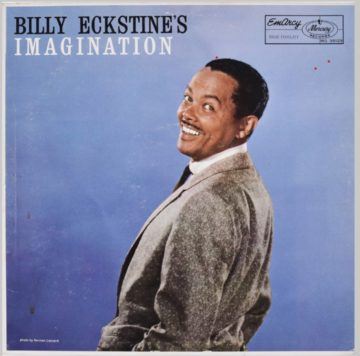

by Dick Edelstein

Not all jazz fans today will understand why an ultra-talented singer and musician like Billy Eckstine aspired to be a famous crooner. But his full, rich bass-baritone voice was ideally suited to that singing style – his voice was as smooth as that of Der Bingle, as Bing Crosby was affectionately known in those days. And crooners were the most admired singers in the 1940s, although it hardly escaped notice that they were all white men. Crosby topped the list of popular crooners – he was idolized by Sinatra – and his style was not merely influenced by jazz; he had built his reputation by fronting prominent jazz bands like the Paul Whiteman Orchestra, whose music suited the taste of white America. Crosby was good at that style of singing, sure, but Billy Eckstine could do as well without breaking a sweat and he wanted to prove it.

In a previous article I discussed how Billie Holiday’s vocals reflected the sound of horn solos. Eckstine, a friend of hers and a contemporary, was part of that story. An innovator, like Holiday, he too incorporated horn styling into his vocals, particularly when he was singing big band arrangements. This came naturally enough since he was a talented horn player who regularly performed on trumpet and trombone. His singing style was not like Holiday’s, but each found their own way of bringing the sound and feeling – and the excitement – of horns into their vocals. Eckstine didn’t imitate Holiday’s mercurial rhythmic shifts and unusual inflections; his vocals sounded more like studied compositions, ornamented with his faultless vibrato, which industry figures called the widest in the business. What the two singers had in common was their use of vocal styling to give expression to lyrics as they incorporated up-to-the-minute styles like progressive jazz and bebop into their expanded palette of vocal effects. Also, both of them were not only composers of popular hits, but successful lyricists as well.

So how great a singer was Eckstine? Read more »

One remarkable redeeming feature of my dingy neighborhood in Kolkata was that within half a mile or so there was my historically distinctive school, and across the street from there was Presidency College, one of the very best undergraduate colleges in India at that time (my school and that College were actually part of the same institution for the first 37 years until 1854), adjacent was an intellectually vibrant coffeehouse, and the whole surrounding area had the largest book district of India—and as I grew up I made full use of all of these.

One remarkable redeeming feature of my dingy neighborhood in Kolkata was that within half a mile or so there was my historically distinctive school, and across the street from there was Presidency College, one of the very best undergraduate colleges in India at that time (my school and that College were actually part of the same institution for the first 37 years until 1854), adjacent was an intellectually vibrant coffeehouse, and the whole surrounding area had the largest book district of India—and as I grew up I made full use of all of these. Unlike her previous exhibit, James chose not to explicitly market

Unlike her previous exhibit, James chose not to explicitly market

The view that everyone who is capable has a basic duty to work and not be idle is the main tenet of what we call the work ethic. Closely related to this are two other ideas:

The view that everyone who is capable has a basic duty to work and not be idle is the main tenet of what we call the work ethic. Closely related to this are two other ideas:

When I was 12 my parents fought, and I stared at the blue lunar map on the wall of my room listening to Paul Simon’s “Slip Slidin’ Away” while their muffled shouts rose up the stairs. As I peered closely at the vast flat paper moon—Ocean Of Storms, Sea of Crises, Bay of Roughness—it swam, through my tears, into what I knew to be my future, one where I alone would be exiled to a cold new planet. But in fact it was just an argument, and my parents still live together—more or less happily—in that same house where I was raised.

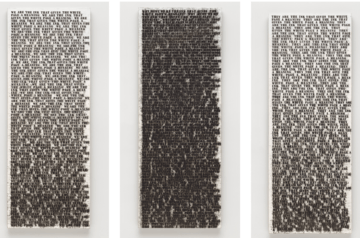

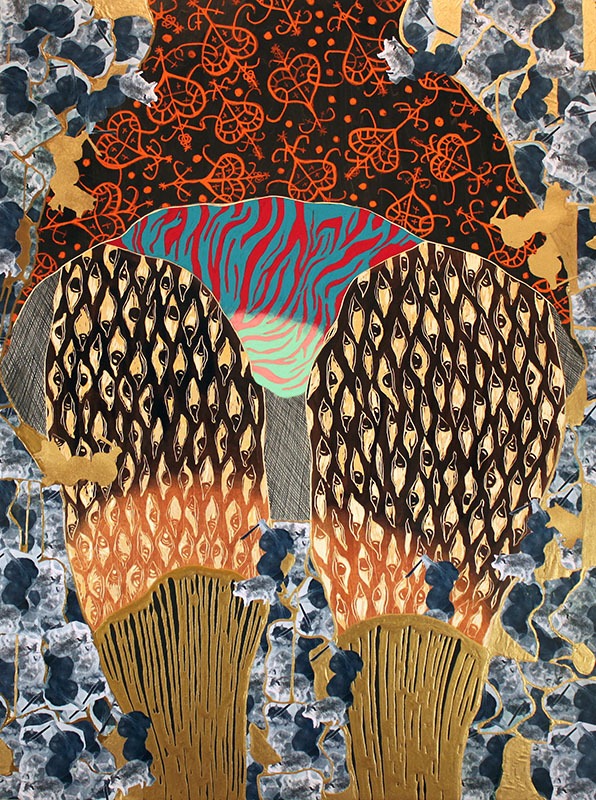

When I was 12 my parents fought, and I stared at the blue lunar map on the wall of my room listening to Paul Simon’s “Slip Slidin’ Away” while their muffled shouts rose up the stairs. As I peered closely at the vast flat paper moon—Ocean Of Storms, Sea of Crises, Bay of Roughness—it swam, through my tears, into what I knew to be my future, one where I alone would be exiled to a cold new planet. But in fact it was just an argument, and my parents still live together—more or less happily—in that same house where I was raised. Didier William. Ezili Toujours Konnen, 2015.

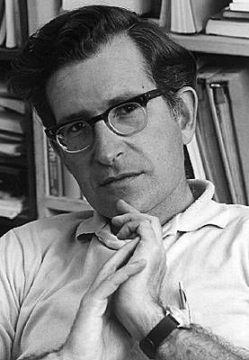

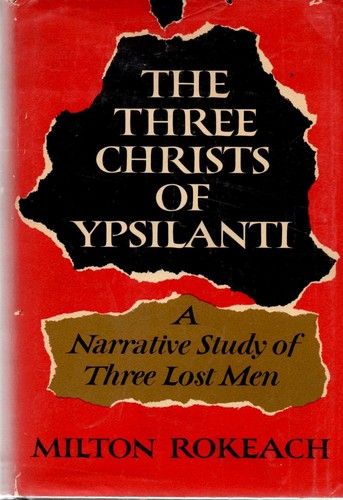

Didier William. Ezili Toujours Konnen, 2015. As an undergraduate History major, I reluctantly dug up a halfway natural science class to fulfill my college’s general education requirement. It was called Psychology as a Natural Science. However, the massive textbook assigned to us turned out to be chock full of interesting tidbits ranging from optical illusions to odd tales. One of the oddest was the story of Leon, Joseph, and Clyde: three men who each fervently believed he was Jesus Christ. The three originally did not know each other, but a social psychologist named Milton Rokeach brought them together for two years in an Ypsilanti, Michigan mental hospital to experiment on them. He later wrote a book titled The Three Christs of Ypsilanti.

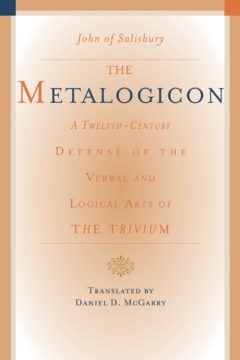

As an undergraduate History major, I reluctantly dug up a halfway natural science class to fulfill my college’s general education requirement. It was called Psychology as a Natural Science. However, the massive textbook assigned to us turned out to be chock full of interesting tidbits ranging from optical illusions to odd tales. One of the oddest was the story of Leon, Joseph, and Clyde: three men who each fervently believed he was Jesus Christ. The three originally did not know each other, but a social psychologist named Milton Rokeach brought them together for two years in an Ypsilanti, Michigan mental hospital to experiment on them. He later wrote a book titled The Three Christs of Ypsilanti. “I am by nature too dull to comprehend the subtleties of the ancients; I cannot rely on my memory to retain for long what I have learned; and my style betrays its own lack of polish.”

“I am by nature too dull to comprehend the subtleties of the ancients; I cannot rely on my memory to retain for long what I have learned; and my style betrays its own lack of polish.”

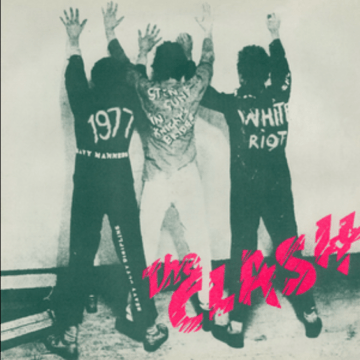

On August 17, 1977, I stopped in as usual at our neighbors’ house, to while away the summer day with my younger brother and sister until our mother’s return home from the university. Our friends – two sets of twins and one singleton – were home-schooled by their mother, and we were all having a summer staycation in any case, so there was always somebody at their house, and a reliably lively time to be had. What met me when I walked into the kitchen that morning, however, was an unaccustomed stillness. All five young people were hovering around the door to the living room while their mother sat at the kitchen table, hunched over a newspaper. “Elvis is dead,” whispered the singleton. Presley had died the day before, in Memphis, in the early afternoon of August 16; but the headlines, and President Carter’s address, would be that day’s news, on the outskirts of Vancouver as elsewhere around the world.

On August 17, 1977, I stopped in as usual at our neighbors’ house, to while away the summer day with my younger brother and sister until our mother’s return home from the university. Our friends – two sets of twins and one singleton – were home-schooled by their mother, and we were all having a summer staycation in any case, so there was always somebody at their house, and a reliably lively time to be had. What met me when I walked into the kitchen that morning, however, was an unaccustomed stillness. All five young people were hovering around the door to the living room while their mother sat at the kitchen table, hunched over a newspaper. “Elvis is dead,” whispered the singleton. Presley had died the day before, in Memphis, in the early afternoon of August 16; but the headlines, and President Carter’s address, would be that day’s news, on the outskirts of Vancouver as elsewhere around the world.