by Chris Horner

Two series have been streaming recently, to considerable success – The Queen’s Gambit (a Netflix miniseries, now concluded) and Succession (HBO, two series so far and more planned). They are interesting for a number of reasons – both for what they show, and perhaps more for what they do not, possibly cannot, show. So let’s consider some of the things we see and don’t see. I’m not going to recount the plot of either of them, as you can get that from Wikipedia and plenty of other places. But: spoiler alert: some will be divulged. Let’s look first at The Queen’s Gambit.

Two series have been streaming recently, to considerable success – The Queen’s Gambit (a Netflix miniseries, now concluded) and Succession (HBO, two series so far and more planned). They are interesting for a number of reasons – both for what they show, and perhaps more for what they do not, possibly cannot, show. So let’s consider some of the things we see and don’t see. I’m not going to recount the plot of either of them, as you can get that from Wikipedia and plenty of other places. But: spoiler alert: some will be divulged. Let’s look first at The Queen’s Gambit.

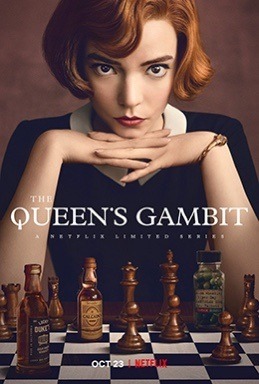

The Queens Gambit‘s success has been enormous. The acting and ‘look’ of the lead -Anya Joy-Taylor – is clearly an important part of it. She even looks on occasion like some elegant chess piece come to life in a Lewis Carroll kind of way. The production values and the way the plot steers away from some (not all!) expected outcomes is also relevant. The theme of success via struggle, including those against ‘inner demons’ isn’t new, but this film (based on a 1980s novel) handles them in an interesting way. But what is this series about? Here are a few suggestions about the world of TQG and what it seems to be saying.

I. TQG is a meticulously crafted fantasy, with many fairytale elements. It has many of the features of a quest/trial story, modified via contemporary psychological and social themes. It even has a ‘helper’ (Jolene) who steps in to give the hero the means she needs to overcome her last trial. It is also a bildungsroman – about how one becomes an adult, or successful self. The themes of mental illness, addiction and abandonment could not be more timely.

II. The story is set in the 50s and 60s but is actually concerning the situation many young people find themselves in now -how one constructs a substitute family when one’s ‘real’ family has failed or disappeared, and how to become a ‘successful self’. Its real theme is about being young now, not in 1966.

III. In a world where the parental function has become dysfunctional, adult figures can no longer be relied on. In fact, their disturbing vulnerability and childishness is a big part of the problem. Her adoptive mother, we soon see, is in no condition to be much more than a permissive older sister. Parents self destruct or abandon you – the mothers die, the fathers leave. Note the way in which older men, ‘father’ figures, both good and bad, feature throughout TQG. From the man who teaches her in the basement, via the selfish foster dad right up to the Russian Grand Master and the old men in the park at the end. Beth tries to control her world with chess and booze and drugs. She gradually learns what friends – a network of others , and the reciprocity that goes with it, really mean. Then she can play (in all senses of the word, and not just to win), and be vulnerable. Moral: a new family has to be made by the young person of 2021.

IV. The film is remarkable in its refusal of sex and romance. Sex happens, but somehow hardly features: people are obsessed with other things, chess, mainly. Gender, on the other hand, does matter- she is the one girl player in a sea of boys, then a lone woman in a sea of men. TQG stages the problem: what does it mean to be a talented women in a world dominated by men? but it does it in an oddly displaced way: the talent is very unusual: utter, world beating, brilliance at chess. Not many will be able to say they know how it feels to be that talented. Chess is able to stand in for anything else one can imagine as a a great talent or ability. It looks for a while as if she will have to be ‘punished’ for this (as in so many narratives of female struggle that isn’t about home and husband) and she is, in a way (addiction etc) – but she is seen to overcome these trials, too.

V. The film somehow cannot deal with two other things: race and class. Two people of colour are in the film, the Shakespeare quoting man who gives out the drugs in the orphanage, and Jolene who is the ‘magic helper’ who gets her off them. Only through the latter do we get anything much about the racial changes in 1960s USA. But it’s a brief and somewhat perfunctory return of the repressed – Jolene’s afro has to do a lot of the signalling here. Class is also absent: the Beth is a the child of people with money, we learn, but we don’t learn much else about that, or them. Work is alluded to a few times, as something some other people do (we don’t see the janitor doing much else but play chess). Unlike most people, most young people in particular, finding steady work and accommodation isn’t a major issue. Not for Beth: plonked into a strangely ‘placeless’ Kentucky house, after leaving the orphanage. Neither place or work matter: the cities we are told she is in don’t really strike us as very strongly imagined. Chess, here, is the place holder: her obsession with it means that her ‘on the spectrum’, nerdy and affectless self gets represented as a gender problem for others. There’s a lot of pleasure for the viewer in seeing her beat the smug men she plays against – but race and class must be somehow repressed..

VI. Institutions – the church, the orphanage, the State Department – exist only to oppress and manipulate you. The Cold War theme has the two nations like quarrelling, manipulative parents. Beth must evade them, too.

VII. The basement that Jolene helps Beth get back to is like her unconscious: only when she goes back and really cries for the first time can she be freed. She can then credit the man who taught her, and name him – Mr Shaibel – in a way that will register with others – although she never paid the $10 she owed him, a debt has somehow been repaid. The death drive (note that her mother actually performs a real death drive ) that has been pushing her can relax its grip: now (after the final contest) she will be able to play, beyond the anhedonic affectless self she has been trapped in.

VIII. In the last big game she will beat and embrace an older man, leave the clutches of the state department man she’s been chaperoned with, and walk towards – who else? chess playing old men who mob her. It’s as if she’s met Mr Shaibel again, but many times over. At this point she is actually dressed like a Queen in a chess game – chic in white, a new self.

‘Let’s play’ she says.

I wonder if she will ever go back to the USA?

Succession presents us with a dysfunctional family that will remind any viewer of the Murdoch clan, although it is just far enough away to avoid libel suits. We have the ageing patriarch of the media and hospitality business (Logan Roy, played by Brian Cox) and his children, Connor, Kendall, Roman and Siobain, any one of whom might succeed him, apparently. The two series screened so far present us with a kind of soap opera of the one percent. Fast moving and with a kind of wit that older versions of this kind of thing (eg 1978s Dallas) couldn’t dream of, it is hugely entertaining and compulsive watching. But what are we seeing is something very post 2008, post Trump even.

Succession presents us with a dysfunctional family that will remind any viewer of the Murdoch clan, although it is just far enough away to avoid libel suits. We have the ageing patriarch of the media and hospitality business (Logan Roy, played by Brian Cox) and his children, Connor, Kendall, Roman and Siobain, any one of whom might succeed him, apparently. The two series screened so far present us with a kind of soap opera of the one percent. Fast moving and with a kind of wit that older versions of this kind of thing (eg 1978s Dallas) couldn’t dream of, it is hugely entertaining and compulsive watching. But what are we seeing is something very post 2008, post Trump even.

For whoever these people are, they aren’t Masters of the Universe. Gone is any glamour that hung around the sharp dealing ‘greed is good‘ characters of the bubble years of financial capitalism (eg Wall Street, 1987, with its Michael Douglas ‘Greed is Good’ tag). No: this is the gang that can’t shoot straight, although it can definitely snort a straight line of coke. Images of capitalist swashbucklers go a lot further back than Wall Street of course: think of The Fountainhead (1949), the film adaptation of Ayn Rand’s preposterous novel about the Genius ‘special man’ who fights his way against the herd, true to his vision etc. And there’s yet more of it in her Atlas Shrugged. But what would Rand think of this lot? They make nothing except ‘deals’, when they are lucky. They are often not lucky.

What we aren’t seeing, pace some reviewers, is ‘capitalism’ or the true power behind politics. Whether a system of value accumulation through exploitation and the extraction of rent is actually presentable in this kind of fiction is unclear. The real focus of the series is elsewhere. The sons of Logan Roy are, in effect, castrated and impotent. Apart from Big Daddy, almost everything they try fails. They back stab, indulge in drug abuse, dodgy sex and self pity. What they do present is the new face of Capitalism’s ‘winners’, as unattractive and useless parasites, puffed with their own self importance. A partial exception seems to be Roy’s daughter, Siobain (‘Shiv’ for short – a nice hard monosyllable that seems to fit her. Can it be a coincidence that ‘shiv’ is old English underworld slang for knife?) who at least is capable of thinking through some of her enterprises. But she too is a monad of ego, aiming at self interest and success, and well described by another character as ‘not as clever as she thinks she is’. The same is true of her useless husband Tom, who alternates between bullying and creeping. Actually, it isn’t quite true to say that the Roy progeny fail at everything. Where they do excel in on occasion is lying, which they can do very effectively, to Congressional Committees, employees or victims of the company who might seek public redress. The exception here is Tom, who cannot even lie convincingly.

It is quite notable that practically all the family company Waystar-Royco (‘a publicly traded multi-billion dollar firm that is involved in Media, Parks, Cruises, Movie Production Studios, and others’) ever does is manoeuvre for market dominance, resisting takeovers, mounting takeovers, (mis) handling PR etc. Here we have capitalists, sort of, who make nothing real in the world, build no bridges, invent no devices that could really change the material world. In this they present something authentically contemporary: the vulture rentier and media class, sucking value from their control of information and real estate. Awash in drugs and drink, every business move is described in violently sexual terms: ‘Let’s f*** them up’, etc.

This is the business world as a bundle pathologies called ‘Roy’. We don’t see race or class much, apart from the servants and victims of the Roys. Any deaths or injuries to this class are labelled by Waystar-Royco as ‘NRPI’, which stands for ‘no real person involved’). This seems to echo the use of ‘NHI’ (‘no human involved’) by some US police forces to refer to deaths of persons of colour, often sex workers or drug addicts. Whole swathes of people don’t qualify for full human status in this world, which is also our world.

Where it may resembleThe Queen’s Gambit is that presents problems in terms of the pathologies stemming from the dysfunctional family. The family’s legacy is the screwed up child, who struggles to make it through and despite the family neuroses. In both the mother is not exactly absent but is in the shadows, and represented by unsatisfactory substitutes. In The Queen’s Gambit family is missing, and is replaced by the search for friends; in Succession we do have a family, but it’s the one from hell, a hot house of manipulation and rivalry that is a machine for pathogenesis. In both there is a search for love or recognition by a Father figure which can only be earned, if at all, by struggle. Beth Harmon should be glad that the Father she seeks isn’t a member of the Roy family.