by Muneeza Shamsie

This year, 26 January marks the fifth death anniversary, of Sahabzada M. Yaqub-Khan (1920-2016), my uncle. To me it seems as if it was yesterday. He was my mother’s youngest brother and her only sibling in Pakistan. The bond between them was so close that I cannot remember a time, when he was not integral to my family life. To my younger sister, Naushaba (now Naushaba Hasnain) and me, he was always ‘Mamou’. I have no idea when Mamou and I first met. He was a prisoner-of-war at the time I was born in Lahore. As I grew up I was told by my parents never to ask him about his POW years because it was such a dreadful experience. I learnt in time, that he had been captured in Egypt (at Bir Hachim after the Battle of Tobruk) and he escaped in Italy with two fellow officers – the future Commander in Chiefs of the Pakistan and Indian armies respectively, Generals Yahya Khan and Kumaramangalam – but they had been recaptured. Mamou was then moved to a concentration camp in Germany. He had utilized those years to learn languages: French, German, Italian and Russian. Afterwards he was sent to England to convalesce. There he was often mistaken for his second cousin, the Nawab of Pataudi, the famous cricketer. The resemblance was so uncanny that two generations later, my daughter Kamila chanced upon a photograph in a book on cricket history. She did a double take and thought ‘What is Yaqub Nana doing here?’

My first conscious memory of Mamou revolves around the unsolved mystery of Fuzzy Wuzzy Kitten, my favourite book. This had big pictures of kitten in a lovely soft, velvety material. Possibly Mamou used to read it to me. One day the book disappeared. For some reason I thought that he was responsible. He would often tease me – and ask with a big grin – until I was quite grown up. “Who took Fuzzy Wuzzy Kitten?” I would point to him. He would go into peals of laughter. And I still don’t know what happened to Fuzzy Wuzzy Kitten.

These early memories are a series of brief images: a window with wooden shutters in Mamou’s room, overlooking flat white rooftops; and his valet Qadir, with rotund stomach and curling moustaches. I have no idea whether these pictures, etched in memory, belong to pre-Partition Delhi, when Mamou was on the Viceroy’s staff, or to post-Partition Karachi, when he was on the Quaid-e-Azam’s staff.

In 1947, my parents, Isha’at and Jahanara Habibullah, moved to Karachi. The following year, Naushaba was born. At one point we stayed with Mamou in a grey, newish block of flats, Fakirjee Lodge in Seafield Road. Eventually, we moved into the flats belonging to my father’s firm, Pakistan Tobacco, on 11 Clifton Road (now the monstrous Glass Towers). The polo ground was nearby. Mamou would drop by in his riding clothes, though it is the gleaming, calf-length, polished leather boots (probably made in London’s Dover Street) that I remember best. There was always a room ready for him, when he was on leave, or in-between postings. He was an avid reader. I particularly recall him exchanging books with an English friend, Francis Humphreys, who was with Burmah Shell and was married to Lady Pamela Wavell. He would appear at our door, with a stack of books under his arm and ask for ‘Yaqub’. (Mamou was also known by the nickname “Jacob” by many friends).

Mamou played an important role in my parents’ decision to send me to England when I was nine. I was doing badly at my studies and he thought I needed the discipline, although in those days people in our social circle sent sons abroad, not daughters (in an earlier generation my father had been sent to England at eight). My mother adored Mamou. She was immensely proud of his achievements. In her eyes he could no wrong. He, in turn, was a very caring brother.

Mamou and my mother had very different personalities but they both loved Urdu poetry, particularly Ghalib. They were also great raconteurs. Both had the gift for conjuring up incidents from another era, honing in on a descriptive detail, a witty comment, or a characterization. These stories contributed to many a lively conversation at home and added to the richness of my family life. But Mamou was not a man to live in the past. He was far more involved in the present. My mother told me that he had been bright, assertive and independent little boy with one ambition: the army. He liked to draw and paint too, as did their sister, Fakhra, a gifted artist. He had inherited his father’s stylishness. His suits and sherwanis were tailored in Saville Row: I learnt from him that the cut of the sherwani is based on the Victorian frock coat.

My grandfather, Sahabzada Sir Abdus Samad Khan died while Mamou was a POW. I only know him through family anecdotes and photographs: a tall, enlightened, good looking man, equally imposing in a turban and sherwani, or in European dress. His children idealized him. He gave his sons the best of education. He allowed his daughters to discard purdah, travel to Europe, and marry of their own choice.

My grandmother – Ammajan, to us – was very different. She was quiet, homey and religious, but full of warmth and affection, endless tact and very particular about good behaviour, neatness and tidiness. I don’t think she had an iota of cunning or malice. I loved her greatly. During her lifetime, my parents, Naushaba and I, would visit her in “Rosaville”, the family home in Rampur, the erstwhile princely state. I have magical memories of that house. A gravel drive curved down from the wrought iron gates. A huge front lawn led to a wooden bridge and stream; beyond were mango groves. The front portion of the main house with its white balustrade, terrace of red brick and fluted arches, constituted the mardana where my grandfather and his three sons – Yusuf, Yunus and Yaqub – had lived. In the drawing room, an exquisite blue and white silk Chinese carpet gave its colours to the upholstery and curtains. Two large Chinese urns guarded the alcove, which led to a terrace, a rose garden and a lotus shaped pond, filled with lilies and goldfish. In the dining room, there was a long, polished dining table and lovely silverware and china; and a few blue and white Chinese poison plates displayed judiciously on the wall. I could well imagine my mother and Mamou growing up in this house. Behind the dining room, a wide corridor separated the mardana from the zenana, where my mother and her two sisters (the eldest became the Begum of Rampur) had been brought up. But no one observed purdah in “Rosaville” when I was there.

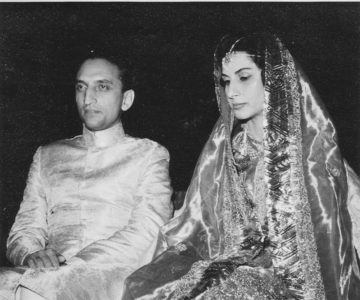

In 1959, during our summer holidays in Karachi, there was great excitement at home, because Mamou was getting married. Naushaba and I were mortified that we had to be back at school and couldn’t attend the wedding, which was quite an event. President Ayub Khan extended the protocol of State Guests to the Nawab and Begum Rampur who came from India, for the occasion. At the time, Mamou was a Brigadier, but in the New Year, he became the youngest Major-General in the Pakistan army.

I met my elegant new aunt, Tuba – Momanijan to me – two years later. She turned out to be tremendous fun, intelligent, and full of life and warmth. She and I became good friends, not just aunt and niece. Momanijan and my father shared a penchant for the unconventional, and an interest in new cuisine. Mamou and my mother were rather conservative about food. Mamou had positively spartan ideas on the subject. He was eternally lecturing the over-indulgent, food-loving Habibullahs, particularly me, on the virtues of eating less. He even took to writing and illustrating comic ditties for me. He was astonished that I managed to lose weight – such was my disastrous proclivity for food (and no exercise.)

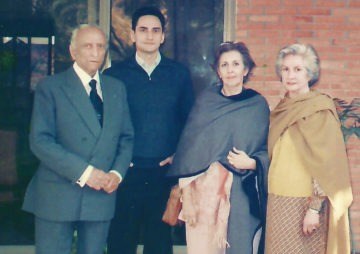

I was 19 when I returned to Pakistan for good. Whenever he was in Karachi, Mamou would take me off to watch polo matches or horror films (Psycho and Dracula). By then Mamou and Momanijan’s eldest, Samad had been born. Najib followed a few years later. My mother reported to her sister Fakhra (with a note of pride) that Mamou had proved to be a remarkably good father. I often stayed with him and Momanijan in Rawalpindi and once, in Quetta, where he was Commandant of the Staff College. In the evenings, while Momanijan and I chatted, Mamou would sit in his winged armchair with an exercise book, pen and notepad, concentrating on the language he was polishing up at the time. He told me that it is mistake to suppose that the acquisition of languages “came naturally” – he had to work hard to keep it up.

Inevitably, language was one of his favourite topics: how the use of words and their construction influenced a national psyche; how the knowledge of another language and its culture alters perceptions and a world view; how a translator can throw an insight into a literature that is perhaps not so apparent to the reader of the original. His multi-lingualism was to stand him in good stead when he became a diplomat, but in the 1960’s no one had any inkling of this. Of course, he read extensively on military matters, but he was very interested in comparative religion and philosophy. His books ranged from Gurdjieff and Ouspensky to Ibn Arabi. Once, he recounted the whole story of The Conference of the Birds by Fariddudin Attar to me and explained its mystical significance. Some of the most stimulating conversations, I have heard have been those in which Mamou took part. My husband, Saleem Shamsie developed a good rapport with Mamou and Momanijan from the very first. Saleem’s sister Amina, was married to Air Marshal Asghar Khan, who had been at the Royal Military Academy, Dehra Dun with Mamou. They were old friends. I think it was thanks to them – both sticklers for time – that everything took place with almost split second military timing at our wedding!

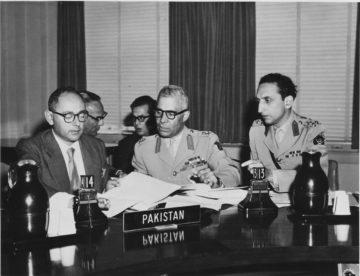

Mamou enjoyed a proximity to the corridors of powers, as long as I can remember. Political discussions with him were always interesting and incisive, but he never indulged in political gossip. Instead, whenever he was engaged in matters of national importance, he maintained a tantalizing silence. This was particularly apparent during his posting to East Pakistan as Chief Martial Law Administrator. During those fateful days, in 1970/71, as negotiation after negotiation failed, the Governor, Admiral Ahsan and Mamou both urged a political solution; while President Yahya, his military advisors and others, pressed for army action. Mamou foresaw the disaster to come. He resigned rather than be a part of it. His letter of resignation, dated March 5, 1971 and his prescient analyses have been published in Anwar Dil’s Strategy, Diplomacy, Humanity: Life and Work of Sahabzada Yaqub-Khan. The rest, as they say, is history.

Mamou loved the army. He had built his life around it. He was never a person to display emotion, but I have never seen him look so sad, as I did, the day his military career ended. As luck would have it, in 1972 the foreign office snapped him up. He was posted as Pakistan’s Ambassador to France and later, Washington, then Moscow. He sent my parents a photograph of himself and Momanijan, in formal dress on the day he presented his credentials at the White House. He inscribed it: “A soldier turned diplomat, malgre soit”. Interestingly, as a diplomat, he developed into a more affable, outgoing personality, whereas as a military man he had been more reserved. He went on to become Pakistan’s longest serving Foreign Minister, and later, Chairman of the Board of the Aga Khan University Hospital.

His public life is well known and others can write about that better than I can. But for me, Mamou was a defining influence in my life and a source of strength. I derive great pleasure from the fact that to my children, Saman and Kamila, he was not just “Yaqub Nana”, a great uncle, but someone very special too.

***

Muneeza Shamsie is the author of a literary history Hybrid Tapestries: The Development of Pakistani Literature in English (2017). She is a co-editor of the online Literary Encyclopedia’s South Asia volumes. She received the Gold IPPY and the 2008 Bronze Foreword prizes in the United States for the Feminist Press edition of her anthology And the World Changed: Contemporary Stories by Pakistani Women (2008, Women Unlimited 2005).

She is the Bibliographic Representative (Pakistan) for The Journal of Commonwealth Literature, serves on several international advisory boards including The Journal of Postcolonial Writing and the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature. She served as a jury member for the latter and for several other literary awards in Pakistan, including The Patras Bokhari Award, and was the regional chair Eurasia of the Commonwealth Writers Prize 2009 and 2010.

She lives in Karachi and writes for Dawn and Newsweek Pakistan.