by Andrew Bard Schmookler

Our contemporary secular worldview, though filled with knowledge and insights, is inadequately developed. It fails to provide the means for comprehending some important realities that religious perspectives — from which the secular culture has departed — were able, in their way, to provide.

It is not surprising that the secular worldview would have some such deficiencies.

- For one thing, it is of relatively recent origin: religious traditions had millennia to develop their systems to provide people the means to understand and cope with the various realities that human life and history compel people to deal with.

- For another, the religious traditions operated with an epistemology that enabled people to “make stuff up,” drawing on a mythological imagination, whereas the predominant epistemology of the secular worldview – to arrive at truth through applying reason to evidence – is far more constraining.

Which just means that there’s more work to be done by us who give our allegiance to that approach to the truth: we need to develop our secular worldview further so that it provides us with more of the understandings that are required to deal with the realities of the human world. Read more »

Now there is a

Now there is a

“Mankind was first taught to stammer the proposition of equality” – “Everyone is equal to everyone else” – “In a religious context, and only later was it made into morality,” Nietzsche wrote. Elsewhere, he called “human equality,” or “moral equality,” a specifically “Christian concept, no less crazy [than the soul],” moral equality “has passed even more deeply into the tissue of modernity…[it] furnishes the prototype of all theories of equal rights.”

“Mankind was first taught to stammer the proposition of equality” – “Everyone is equal to everyone else” – “In a religious context, and only later was it made into morality,” Nietzsche wrote. Elsewhere, he called “human equality,” or “moral equality,” a specifically “Christian concept, no less crazy [than the soul],” moral equality “has passed even more deeply into the tissue of modernity…[it] furnishes the prototype of all theories of equal rights.”

Port Sunlight was a model village constricted in the Wirral, in the Liverpool area, by the Lever brothers, and especially under the inspiration of William Lever, later lord Leverhulme. Their fortune was based on the manufacture of soap, and the village was built next to the factory in the Victorian/Edwardian era, for the employees and their families. It’s certainly a remarkable place, with different houses designed by various architects, parks, allotments, everything an Edwardian working class person might want. An enlightened employer, Lever was still a paternalist: he claimed his village was a an exercise in profit sharing, because “It would not do you much good if you send it down your throats in the form of bottles of whisky, bags of sweets, or fat geese at Christmas. On the other hand, if you leave the money with me, I shall use it to provide for you everything that makes life pleasant – nice houses, comfortable homes, and healthy recreation.” Overseers had the right to visit any house at any time to check for ‘cleanliness’ and that the rules about who could live in which house were observed (men and women could only share accommodation if they were in the same family). Still, by the stands of the day it was quite progressive – schools, art gallery, recreation of all sorts for the employees were important.

Port Sunlight was a model village constricted in the Wirral, in the Liverpool area, by the Lever brothers, and especially under the inspiration of William Lever, later lord Leverhulme. Their fortune was based on the manufacture of soap, and the village was built next to the factory in the Victorian/Edwardian era, for the employees and their families. It’s certainly a remarkable place, with different houses designed by various architects, parks, allotments, everything an Edwardian working class person might want. An enlightened employer, Lever was still a paternalist: he claimed his village was a an exercise in profit sharing, because “It would not do you much good if you send it down your throats in the form of bottles of whisky, bags of sweets, or fat geese at Christmas. On the other hand, if you leave the money with me, I shall use it to provide for you everything that makes life pleasant – nice houses, comfortable homes, and healthy recreation.” Overseers had the right to visit any house at any time to check for ‘cleanliness’ and that the rules about who could live in which house were observed (men and women could only share accommodation if they were in the same family). Still, by the stands of the day it was quite progressive – schools, art gallery, recreation of all sorts for the employees were important.

In 1930, the German anthropologist Berthold Laufer published a monograph on the phenomenon of people eating dirt.

In 1930, the German anthropologist Berthold Laufer published a monograph on the phenomenon of people eating dirt. My grandmother’s bird of choice is the rooster. She was raised in rural Kentucky and now lives in rural Wisconsin. She collects all sorts of roosters (and, by extension, some hens): wall art, printed dish towels, ceramic statues as small as a pinky and as large as a lamp, coin bowls and blankets and something nostalgic in each one.

My grandmother’s bird of choice is the rooster. She was raised in rural Kentucky and now lives in rural Wisconsin. She collects all sorts of roosters (and, by extension, some hens): wall art, printed dish towels, ceramic statues as small as a pinky and as large as a lamp, coin bowls and blankets and something nostalgic in each one.

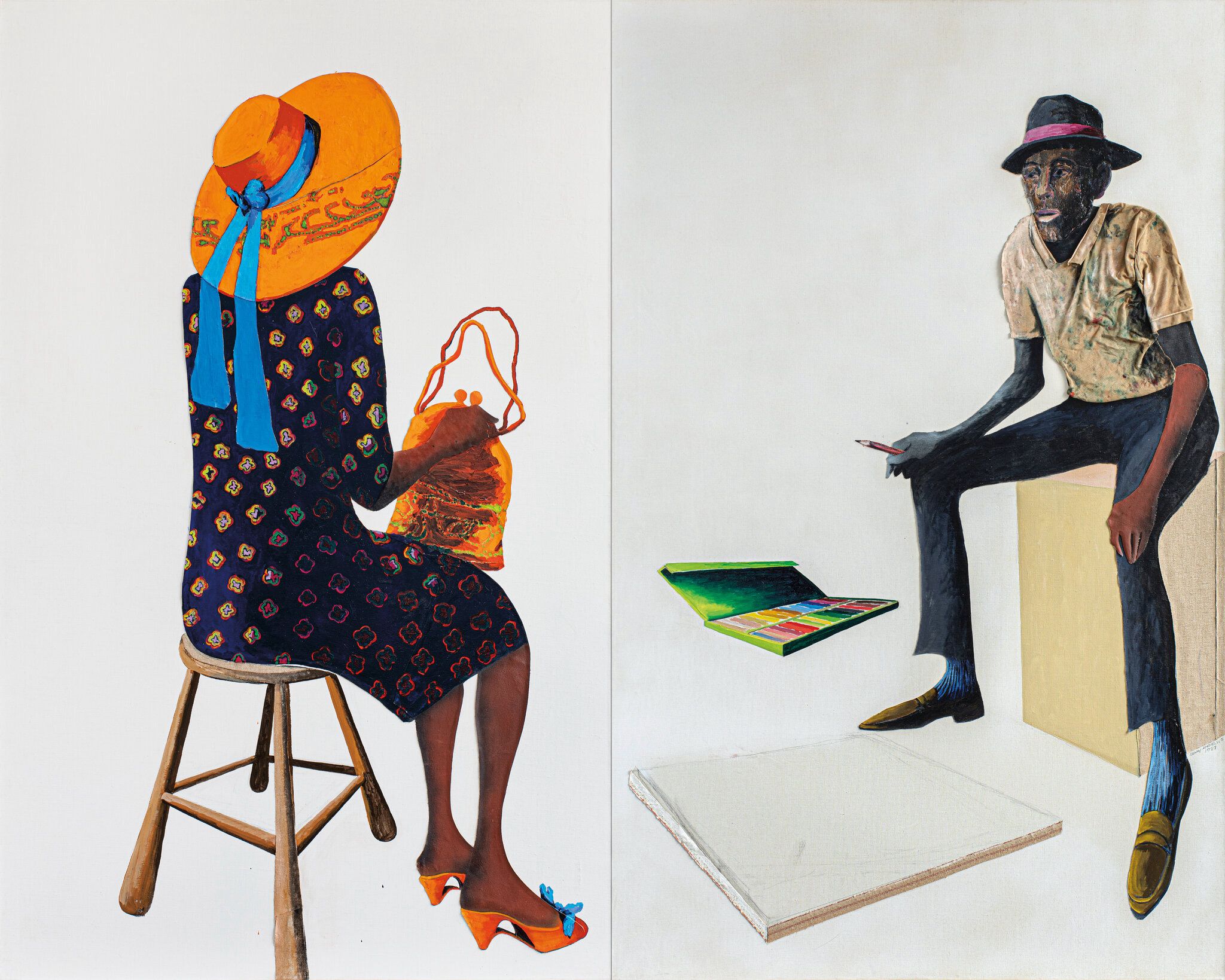

Sughra Raza. Shadow Self-Portrait in a Reflection of a Window in a Window.

Sughra Raza. Shadow Self-Portrait in a Reflection of a Window in a Window.  A couple of years ago I briefly became famous for hating Vancouver. By “famous” I mean that a hundred thousand people or so read

A couple of years ago I briefly became famous for hating Vancouver. By “famous” I mean that a hundred thousand people or so read