by Brooks Riley

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

by Brooks Riley

by Sarah Firisen

For a long time, an accepted principle of corporate life has been that to take advantage of spontaneous ideation to drive innovation, people need to be in the same physical space. To encourage innovation, Apple, the accepted exemplar of an innovative company, built its headquarters in such a way as to try to spark these innovative interactions; “It’s hoped that by housing so many employees in one facility, workers will be more likely to build relationships with those outside of their team, share ideas with co-workers with different specialties and learn about opportunities to collaborate.”

For a long time, an accepted principle of corporate life has been that to take advantage of spontaneous ideation to drive innovation, people need to be in the same physical space. To encourage innovation, Apple, the accepted exemplar of an innovative company, built its headquarters in such a way as to try to spark these innovative interactions; “It’s hoped that by housing so many employees in one facility, workers will be more likely to build relationships with those outside of their team, share ideas with co-workers with different specialties and learn about opportunities to collaborate.”

Another principle, as this McKinsey piece claims, is that “Innovation is a team sport….when it comes to innovation, it is rare to see individuals who possess the full range of skills needed to lead an initiative.” And, at least until March 2020, the assumption was that the only successful way to collaborate creatively was in person. The brainstorming workshop, or team whiteboarding off-site, was something that most of us in white-collar jobs have been part of in some form or at some time.

At this point, it’s not news that many, maybe even most, of the white-collar workers who have been able to work remotely throughout the pandemic don’t want to return to the office. I’ve written about the, perhaps surprising, results of the unforeseen work-from-home mass experiment: productivity and worker satisfaction are up. And while some companies, particularly financial institutions, are starting to demand that people come in for at least 2-3 days a week, other companies are beginning to accept the reality that they may never be able to force everyone to be in the office regularly. Read more »

by Andrew Bard Schmookler

Our contemporary secular worldview, though filled with knowledge and insights, is inadequately developed. It fails to provide the means for comprehending some important realities that religious perspectives — from which the secular culture has departed — were able, in their way, to provide.

It is not surprising that the secular worldview would have some such deficiencies.

Which just means that there’s more work to be done by us who give our allegiance to that approach to the truth: we need to develop our secular worldview further so that it provides us with more of the understandings that are required to deal with the realities of the human world. Read more »

My friend Ruchira Paul showed me a little trick to cook blue rice using tea made from the dried flowers of Blue Butterfly Pea plants. Shown here: a small appetizer plate with some greens, the blue rice (which smells and tastes like normal basmati rice), masoor daal (lentils), and some cheese and tomatoes.

Here’s the scene: A middle school auditorium in suburban New Jersey early in the Fall. It’s late Saturday afternoon on the second day of a dance competition. The auditorium is filled—but only loosely—with young dancers and their parents, other family, and friends. They’re all waiting for the final performance of the competition.

Some hip hop comes up on the sound system and a few of the dancers begin moving to the music. Some of them are standing up from their positions in the audience and are dancing in place. A couple others, at the far-left and far-right down front, are dancing in the outside aisles. More start joining in.

Down front, in the center, the action photographer—the guy who’s there to shoot photos of each dance number so they can then be sold to parents—is sitting down front on his high swivel chair. He’s smiling, swiveling in the chair to survey the scene, and he starts clapping on the back-beat.

That’s me.

Now another hip hop number comes up and, in a whooshhh! dancers get up out of their seats, rush to the aisles, and the aisles are jammed with kids joyously dancing. Five, six, eight, eleven, fifteen years old, a few older. Even the dancers waiting in the wings on stage for the final number, they danced too.

All dancing. 100, 200, maybe more. Dancing.

It was wonderful. Read more »

by Jim Britell

The roots of the epic transfer of wealth from the middle and lower classes to the rich which began with Reagan and peaked with the recent billionaire explosion can be traced to a series of events between March and November 1968.

July 1967 – Thousands converge in San Francisco for the Summer of Love

March 1968 – Robert Kennedy enters the Democratic Primary for President

April 1968 – Martin Luther King assassinated

June 1968 – Robert Kennedy assassinated

August 1968 – 75 million watch 5000 protesters clubbed and beaten on national television at the democratic convention in Chicago

January 1969 – Nixon sworn in as president

August 1969 – Woodstock

These events estranged a whole generation of young people who concluded that working within the political process was definitely not hip. They abandoned the political process. Many radicals, progressives, liberals and populists have avoided “hands on” electoral politics ever since. Read more »

by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

In a democracy, political decisions are typically made by way of elections. In winner-take-all systems, elections produce winners and losers. It seems natural, then, that in the United States our talk about democracy tends to focus on the competitive aspects of politics. For example, processes for filling political offices are called “contests” and “races”; candidates for such offices are called “contenders” and “hopefuls”; and electoral wins are called “victories,” while losses are called “defeats.” When a candidate loses especially decisively, we reach for stronger language; we sometimes say the candidate was “trounced” or side was “clobbered.” Our popular political vocabulary closely resembles the way we talk about sports. So, in addition to wins, losses, and races, there are cases of running up the score, playing out of bounds, and even spiking the political football.

Seizing on this, candidates and commentators tend to proceed as if political wins are deeply like sports victories. Winners present themselves not only as having prevailed against the other candidates, but also as having defeated everything the opposing side stands for. The team that wins the World Series is thereby the champion, and there’s nothing for the other teams to do other than begin training for next season; similarly, winning candidates tend to proceed as if those they prevailed against are relegated to a similar status: they must reconcile themselves to their losses, step aside, and look towards the next election.

Of course, part of the reason why the sporting vernacular is so prominent in our politics is that it indeed captures fundamental features of how democracy in the United States works. As we noted at the beginning, our winner-take-all elections really do produce winners and losers. So, that similarity is not an illusion. However, the similarity with sports goes only so far, and it is shallower along other lines than its prominence may suggest. Read more »

“So, after all these millennia,

what are you best at, my man?

What rocks your boat,

what stokes your passion,

what makes your day?” God asks

His creature

His creature replies,

“What I love most is conflict.

It’s what I do most reflexively

(not counting ruts of lust), and in

serial manner I might add,

down bloody centuries.

What I do best, my specialty,

is war —if I must say so myself,”

“And why do you think

this is so?” asks God.

“Isn’t that something only

you would know?” replies

His creature, paraphrasing

Dylan

Jim Culleny

10/10/22

by Jonathan Kujawa

Some years ago we discussed Brobdingnagian numbers. You can find the 3QD essay here. These are numbers that are so mind-bogglingly large they defy human imagination. Perhaps the most famous is Graham’s number. It’s so large I can’t write it down for you. It’s not that I refuse to write it down; I can’t. If I used one Planck volume per digit, Graham’s number would take up more than the observable universe [1]. Still, we would like to use and study such numbers and other hard-to-contemplate mathematical objects.

With the advent of computers and computer science, one reasonable way to describe a mathematical object is via a computer algorithm. That is, a step-by-step recipe that describes the number or question we are interested in and that could (at least in principle) be implemented on a computer. This is a pretty reasonable way to ringfence the parts of mathematics on which we might claim our minds can handle (maybe with help from computers).

For example, computable numbers are real numbers that are knowable in this sense. If we want to know the number’s nth digit, we can write down an algorithm that computes that nth digit for us. Even though the digits of π go on forever and have no discernable pattern, we have such algorithms for the digits of π, so it is computable. Likewise, there is a recursive formula for Graham’s number. It, too, is computable.

We aren’t limited to numbers. In a pair of 3QD essays last year (here and here), we saw that mathematicians have made significant progress in turning mathematics and mathematical thinking into things a computer can work with. There we saw machine learning help mathematicians make new connections and insights, and theorem verification software can help check the validity of results.

Before getting too cocky, it is worth remembering that we learned that most real numbers aren’t computable. Things that are computable go far beyond our everyday experience, but we shouldn’t forget there are vast seas beyond computable’s shores.

With this in mind, it is perhaps worth trying to understand the limits of what is computable. Read more »

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

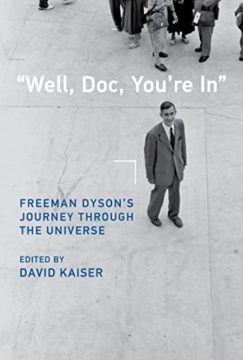

Freeman Dyson combined a luminous intelligence with a genuine sensitivity toward human problems that was unprecedented among his generation’s scientists. In his contributions to mathematics and theoretical physics he was second to none in the 20th century, but in the range of his thinking and writing he was probably unique. He made seminal contributions to science, advised the U.S government on critical national security issues and won almost every award for his contributions that a scientist could. His understanding of human problems found expression in elegant prose dispersed in an autobiography and in essays and book reviews in the New Yorker and other sources. Along with being a great scientist he was also a cherished friend and family man who raised six children. He was one of a kind. Those of us who could call him a friend, colleague or mentor were blessed.

Now there is a volume commemorating his remarkable mind from MIT Press that is a must-read for anyone who wants to appreciate the sheer diversity of ideas he generated and lives he touched. From spaceships powered by exploding nuclear bombs to the eponymous “Dyson spheres” that could be used by advanced alien civilizations to capture energy from their suns, from his seminal work in quantum electrodynamics to his unique theories for the origins of life, from advising the United States government to writing far-ranging books for the public that were in equal parts science and poetry, Dyson’s roving mind roamed across the physical and human universe. All these aspects of his life and career are described by a group of well-known scientists and science writers, including his son, George and daughter, Esther. Edited by the eminent physicist and historian of science David Kaiser, the volume brings it all together. I myself was privileged to write a chapter about Dyson’s little-known but fascinating foray into the origins of life. Read more »

Now there is a volume commemorating his remarkable mind from MIT Press that is a must-read for anyone who wants to appreciate the sheer diversity of ideas he generated and lives he touched. From spaceships powered by exploding nuclear bombs to the eponymous “Dyson spheres” that could be used by advanced alien civilizations to capture energy from their suns, from his seminal work in quantum electrodynamics to his unique theories for the origins of life, from advising the United States government to writing far-ranging books for the public that were in equal parts science and poetry, Dyson’s roving mind roamed across the physical and human universe. All these aspects of his life and career are described by a group of well-known scientists and science writers, including his son, George and daughter, Esther. Edited by the eminent physicist and historian of science David Kaiser, the volume brings it all together. I myself was privileged to write a chapter about Dyson’s little-known but fascinating foray into the origins of life. Read more »

by Tim Sommers

“Mankind was first taught to stammer the proposition of equality” – “Everyone is equal to everyone else” – “In a religious context, and only later was it made into morality,” Nietzsche wrote. Elsewhere, he called “human equality,” or “moral equality,” a specifically “Christian concept, no less crazy [than the soul],” moral equality “has passed even more deeply into the tissue of modernity…[it] furnishes the prototype of all theories of equal rights.”

“Mankind was first taught to stammer the proposition of equality” – “Everyone is equal to everyone else” – “In a religious context, and only later was it made into morality,” Nietzsche wrote. Elsewhere, he called “human equality,” or “moral equality,” a specifically “Christian concept, no less crazy [than the soul],” moral equality “has passed even more deeply into the tissue of modernity…[it] furnishes the prototype of all theories of equal rights.”

There is some evidence for this view.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident,” says America’s Declaration of Independence, “that all men [sic] are created equal…” “Self-evident” is not in the first draft. It appears in Benjamin Franklin’s, not Jefferson’s, handwriting. Franklin apparently struck out what Jefferson had written and replaced it with “self-evident” – a philosopher’s word. Jefferson had written “sacred & undeniable.” His first draft also specified that people weren’t just created as equals, but that it was “from that equal creation [that] they derive their rights inherent & unalienable.” (We should also note that, ironically, though quite typically, Jefferson equates human equality with equality between men, in fact, he implicitly presupposes that only white, property-owning men or equals. Equality has excluded as well as included.)

Nietzsche isn’t the only one who thinks that moral equality is a Christian idea. The “Judeo-Christian idea of equality,” that “All humans are of equal and positive worth because of some intrinsic property,” Louis Pojman has argued, “must be grounded in a transcendent reality, one that is not discoverable apart from religious authority.” Read more »

by Robyn Repko Waller

Cringy. Real. Surreal. Socially Suspect. A lot can (and has been) said about Nathan Fielder’s HBO docu-comedy The Rehearsal. Are the clients actors? Are the actors acting? Is Fielder an actor or client? Script becomes life and life becomes script in a recursive dream (nightmare?) of which one cannot help but be an onlooker. [Season 1 spoilers ahead.]

The initial premise seems wholesome if it was not so intrusive. Help folks live out their fraught future endeavors with a host of trained actors, replica sets, and practically limitless rewinds. ‘Immersive’ doesn’t do The Rehearsal justice. Fielder, the former magician, spins realism. Fielder and HBO seem to spare little expense to engineer clients’ test scenarios — the full-scale bustling bar down to the torn chairs and spices and patrons, an Oregon farmhouse homestead with the dream garden and steady supply of child actors. Creator of worlds of possibility. Worlds of possibility for action and transformation.

But can being embedded in a rich social simulation transform us? Prepare us for a changed future self? Plenty of shows and movies exploit the intrigue of transformation to capture viewers, but few are philosophical enough to explore the conditions for transformation, for shaping the self. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Christopher Horner

Port Sunlight was a model village constricted in the Wirral, in the Liverpool area, by the Lever brothers, and especially under the inspiration of William Lever, later lord Leverhulme. Their fortune was based on the manufacture of soap, and the village was built next to the factory in the Victorian/Edwardian era, for the employees and their families. It’s certainly a remarkable place, with different houses designed by various architects, parks, allotments, everything an Edwardian working class person might want. An enlightened employer, Lever was still a paternalist: he claimed his village was a an exercise in profit sharing, because “It would not do you much good if you send it down your throats in the form of bottles of whisky, bags of sweets, or fat geese at Christmas. On the other hand, if you leave the money with me, I shall use it to provide for you everything that makes life pleasant – nice houses, comfortable homes, and healthy recreation.” Overseers had the right to visit any house at any time to check for ‘cleanliness’ and that the rules about who could live in which house were observed (men and women could only share accommodation if they were in the same family). Still, by the stands of the day it was quite progressive – schools, art gallery, recreation of all sorts for the employees were important. Read more »

Port Sunlight was a model village constricted in the Wirral, in the Liverpool area, by the Lever brothers, and especially under the inspiration of William Lever, later lord Leverhulme. Their fortune was based on the manufacture of soap, and the village was built next to the factory in the Victorian/Edwardian era, for the employees and their families. It’s certainly a remarkable place, with different houses designed by various architects, parks, allotments, everything an Edwardian working class person might want. An enlightened employer, Lever was still a paternalist: he claimed his village was a an exercise in profit sharing, because “It would not do you much good if you send it down your throats in the form of bottles of whisky, bags of sweets, or fat geese at Christmas. On the other hand, if you leave the money with me, I shall use it to provide for you everything that makes life pleasant – nice houses, comfortable homes, and healthy recreation.” Overseers had the right to visit any house at any time to check for ‘cleanliness’ and that the rules about who could live in which house were observed (men and women could only share accommodation if they were in the same family). Still, by the stands of the day it was quite progressive – schools, art gallery, recreation of all sorts for the employees were important. Read more »

by Eric Bies

In 1930, the German anthropologist Berthold Laufer published a monograph on the phenomenon of people eating dirt.

In 1930, the German anthropologist Berthold Laufer published a monograph on the phenomenon of people eating dirt.

A sinologist by training, Laufer’s study—“the evaluation of the whole question of geophagy”—begins with a trip through Ancient China, where for hundreds of years Han, T’ang, and Sung soil disappeared down eager gullets. From there, the globe: he tours Malaysia, Polynesia, Melanesia, Australia, India, Burma, Siam, Central Asia, and Siberia, stopping off among Persians and Arabs before continuing on to Africa, Europe, North America, Mexico, Central America, and South America. His conclusion? People all over have eaten dirt for a very long time … And yet rarely does one find a Malaysian or an Indian, a Siberian or an Arab, an African or a Mexican swallowing down the plucked clod raw. Almost always water is added to the earth first: in the Yun-ho Mountains, white clay “is mixed with water and beaten on a stone” before it is eaten; in the Philippines, “it is a common thing to mix the earth taken from the nests of ‘white ants’ with water”; in Nishapur, where Omar Khayyam penned his Rubáiyát, the clay is softened with “rose-water and a little camphor,” then shaped into loaves.

Of course, few have particularly prized the practice Laufer describes in all its inventive renditions: as when the occupants of Leningrad remained under unremitting siege for 872 days and turned, in the interest of evading death by starvation, to their suppers of book glue and snow, so the chronically hungry everywhere and forever have tended to eye the lumps of mud out back with all the despairing expediency of a cratered gut.

Even now it remains common practice in the poorer parts of places like the Subsaharan to attempt to recuperate certain vital minerals as iron, calcium, and zinc, including incidental traces of vitamins B and C, through a sometime diet of dirt. Read more »

by Ethan Seavey

My grandmother’s bird of choice is the rooster. She was raised in rural Kentucky and now lives in rural Wisconsin. She collects all sorts of roosters (and, by extension, some hens): wall art, printed dish towels, ceramic statues as small as a pinky and as large as a lamp, coin bowls and blankets and something nostalgic in each one.

My grandmother’s bird of choice is the rooster. She was raised in rural Kentucky and now lives in rural Wisconsin. She collects all sorts of roosters (and, by extension, some hens): wall art, printed dish towels, ceramic statues as small as a pinky and as large as a lamp, coin bowls and blankets and something nostalgic in each one.

If you don’t mind stepping briefly into her condo, we can see what it’s like. Eyes everywhere. Thoughtless, energetic eyes. Suspicion and preparedness. A rooster’s eye is life because it is anxiously awake, unsure why, but it is safe because it is always aware of sources of suspicion; suspicion, of course, comes from an abundance of anxiety. So those eyes don’t think much about what they’re watching. I’m sure you’ll find it hard to find hundreds of rooster eyes in your peripheral vision, but you’ll get used to it. If you feel overwhelmed, you can look outside her large windows, you can see the small and glassy lake with sailboats gliding over its surface like razors through taut fabric.

My mother’s bird of choice is the crow. She unconsciously developed an uncanny connection with them. It started during our group quarantine, after the onset of the pandemic. We spent April through May isolated in our ski cabin. We had no friends there so we could not be tempted to socialize. We could social distance easily, with the majority of the houses nearby sitting empty, their owners waiting for the ski resort to reopen. Read more »

Editor’s Note: Frans de Waal’s new book, Different: Gender Through the Eyes of a Primatologist, has generated some controversy and misunderstanding. He will address these issues in a series of short essays which will be published at 3QD and can all be seen in one place here. More comments on these essays can also be seen at Frans de Waal’s Facebook page.

by Frans de Waal

Since men lack a nurturing instinct, we can’t expect them to take care of kids. It would be “unnatural.”

This false appeal to biology is often heard in defense of traditional gender roles. Thus, Fox News’ Tucker Carlson mocked the paternity leave of U.S. Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg as a way of “trying to figure out how to breastfeed.”

At first sight, the behavior of other primates supports the assertion that caretaking is not for males. Male apes may offer protection to mothers and young, but that’s all. Raising offspring is a female job. The maternal load is so heavy that bonobos and chimpanzees get pregnant only every five or six years. They cannot handle more progeny. Mothers carry the youngest on their belly, a juvenile on their back, while an older one follows them through the forest. Young apes remain dependent for up to a decade, and mothers receive no assistance to speak of.

But oddly (or perhaps not so oddly if we assume that the genders are psychologically more similar than different), males are perfectly capable of childcare. They have a remarkably well-developed caring “potential”. We sometimes get a glimpse of this potential after a mother’s death, when there is all of a sudden an orphan whimpering for attention. Read more »

by John Allen Paulos

I recall a party game I once wrote about. The game, described by philosopher Daniel C. Dennett in his book “Consciousness Explained,” is a variant of the familiar childhood game requiring that one try to determine by means of Yes or No questions a secretly chosen number between one and one million. (Twenty questions are sufficient.)

In Dennett’s more interesting and suggestive game, one person is selected from a group of people at a party and asked to leave the room. He (or she) is told that in his absence one of the other partygoers will relate a recent dream to the other attendees. The person selected returns to the party and is then told that, through a sequence of Yes or No questions about the dream, he should try to do two things: reconstruct the dream and identify whose dream it was.

The punch line is that no one has related any dream. When asked, the individual partygoers are instructed to respond either Yes or No to the subject’s questions according to some completely arbitrary rule. Any rule will do, but should be supplemented by a non-contradiction clause so that no answer directly contradicts an earlier answer or contradicts obvious facts. The Yes or No requirement can also be loosened to allow for an occasional Maybe.

Now let me change the scene. Instead of the unlucky partygoer, consider an ardent QAnon member. Instead of the other partygoers let’s substitute people who pretend to be from the news media (to rouse the member’s antagonism) but who agree to be governed by similar arbitrary rules. Finally, rather than having the subject try to reconstruct the dream and identifying the dreamer, let’s examine whatever disgusting scandal the QAnon member believes to be the case and to whom he attributes it.

Clearly this is more a thought experiment than an empirical result, but I would guess that the likely outcome in both cases is that the subject, impelled by his (or her) own obsessions, will often concoct an outlandish dream or gruesome story in response to the random answers he elicits from the partygoers or the “media” people. The situation is a kind of Rorschach test without the inkblots. Read more »