by Andrea Scrima

March 1, 2022

I left Florence exactly two years ago, a week after the first Corona lockdowns went into effect on February 22, 2020; I returned to the city for the first time yesterday, just as Russian attacks on Ukraine shifted into full gear. Back in Berlin, the war felt suddenly very close: we share a peculiarly intense, at times numinous northern continental winter light with our neighbors to the East; we are united by weather fronts, massive drifts of leaden, seemingly immobile nimbostratus clouds inching slowly across the North European Plain through Poland and Belarus and drifting farther east and south, eventually yielding to the frigid Siberian High and the weather patterns of the Black Sea Lowland. Moving eastward, the clement maritime climate of the western plains gradually gives way to harsher temperatures: summers are hotter, winters bitter cold. The day before yesterday, as over 100,000 people gathered in Berlin between the Victory Column and the Brandenburg Gate to protest the Russian invasion, the sky was sunny and clear, and although there was still a frigid bite in the air, the snow covering the streets of Lviv and Kharkiv and Kiev had either passed us by or was blown into Ukraine from the northeast. Martius, named after the Roman god of war, marked the beginning of the ancient calendar year and the resumption of military campaigns following a winter hiatus. Today, on the first of this ominous month, a forty-mile-long Russian convoy is approaching Kiev. It’s just above freezing there; precipitation is in the forecast for the next several days, expected to give way to subzero temperatures. People will be bombed out of their homes and forced to flee in the freezing rain; later, the slush on the rubble-strewn roads will turn to ice, making their journey on foot even more arduous.

When I got off the train yesterday at Santa Maria Novella, I was convinced that I remembered the way; I knew that I needed to take the 36 or 37 bus, but the stop I recalled turned out to be the Capolinea, the end of the line where I disembarked two years ago, over an hour early for my train departing Florence—upon which, to kill time, I wandered around the neighborhood of San Marco, lugging my suitcase behind me in the early-morning serenity of the still-deserted streets. I remember wondering if this mysterious new epidemic would remain confined to its various pockets of outbreak, when all at once, as I turned the corner onto Via Nazionale, the brightly lit letters of Hotel Corona stopped me in my tracks.

As with my arrival in Florence two years ago, it took me some time to find the bus stop, just enough for a vague sense of anxiety to set in. I was traveling by choice, I had an invitation and a room to stay in, and yet the news images of people fleeing first the advance of Russian troops on the Donbas and then everywhere else superimposed themselves onto the bustling Florentine streets: people abandoning their cars and possessions after running out of gas in thirty-mile-long traffic jams headed west for the border checkpoints; men pulled out of queues by Ukrainian soldiers and forced to bid goodbye to their families and join the armed resistance. Children with bunny ears on their woolen caps alarmed and wailing, their faces turned away or pressed to the foggy windows of buses and trains, their mothers unable to console them. Women carrying toddlers in snowsuits and diaper bags and lugging suitcases behind them, bracing for hours on foot in the freezing cold to reach a border or train station even as students and other people from non-white countries are turned back from the checkpoints and often beaten. People hauling cats and dogs on their backs, their children in tow, most of them too exhausted or too numbly focused on surviving the next minutes and hours to cry. The sight of their shock and their uprootedness slices into the marrow and fuels my own temporary lack of orientation, my struggle to conserve the last six percent battery power on my cell phone. I backtrack several times, perspiring and unable to properly concentrate, knowing all the while that I am headed to warmth and safety, to privilege. It eventually occurs to me that I can check Google Maps, and I finally find the bus stop, ashamed at my lack of resourcefulness, at my porosity and empathy that help no one.

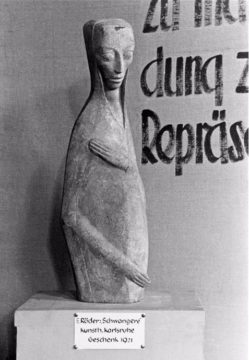

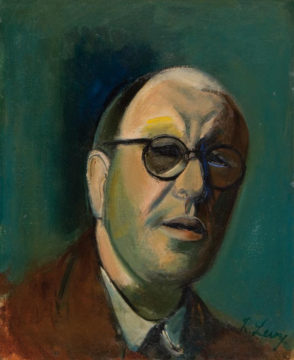

The Villa Romana, where I am currently a guest, is Germany’s longest-standing artist’s residency; it also has a history of displacement and refuge. During the rise of the National Socialist regime and throughout the war years, a small circle of exiled Jewish artists and intellectuals formed in Florence and mingled with the Villa community. The painter Hans Purrmann, director of the institution, invited one of the artists working here, Emy Roeder, to remain when her six-month stipend came to an end; her sculpture of a pregnant woman had just been displayed in the infamous “Degenerate Art” exhibition in Munich and her work officially banned, and she had reason to fear a return. In December of 1940, a long-time friend of Purrmann’s, Rudolf Levy, arrived in Florence following seven troubled years in European exile and a failed attempt to emigrate to New York. By this time, the German museums that had purchased his works—among them the Kronprinzenpalais in Berlin, the Kunsthalle in Hamburg, and the Wallraff-Richartz Museum in Cologne—had removed them from their collections; the same fate had befallen Purrmann’s work. Emy Roeder moved into a small apartment under the Villa’s roof; Levy rented a studio in the Pensione Sorelle Bandini on the top floor of the Palazzo Guadagni on nearby Piazza Santo Spirito, the same building that housed the Kunsthistorisches Institut. The young Werner Haftmann—whose famous Painting in the Twentieth Century would later become a key reference work in the curriculum of most art schools from the mid-sixties on—lived in Florence from 1936 to 1940 and worked as an assistant here. His office was situated one floor below Levy’s atelier.

Beginning in 1933, Jews were forbidden to enter the Institute; in 1938, they were expelled from membership in its association altogether. That same year, a twenty-six-year-old Haftmann and the Institute’s director, Friedrich Kriegbaum, took part in an official state visit. Wearing party uniforms, they led Hitler and Mussolini through the Palazzo Pitti and the Vasari Corridor over the Ponte Vecchio and on to the Uffizi and the Palazzo Vecchio. Four days later, on May 13, Kriegbaum was struck by the idea of sending the Führer a personal album containing photographs of all 160 works he’d viewed that day. To be safe, he decided to check first with the undersecretary if a commemorative gift of this kind on the part of the Kunsthistorisches Institut would be interpreted in any way as inappropriate or intrusive, after which, reassured and encouraged, he wrote an obsequious letter to the privy councilor Ernst Heinrich Zimmermann, asking for permission to create the album. For his part, Haftmann contributed an article to a special issue of Firenze magazine published to celebrate the illustrious visit. On the cover is an eagle spreading its wings against a diagonal red banner with a swastika; in the background, three equally grim-looking eagles are flying past the Palazzo Vecchio, resembling a fleet of warplanes more than birds.

After the war’s end, Haftmann went on to become a highly influential art historian, curator, and museum director; it’s only recently that details of his earlier political affiliations and war activities have come to light. In 1933, still a student, he joined the uniformed paramilitary of the SA, which played a key role in the National Socialists’ rise to power; it can be assumed that he was involved in disruptive activities in Berlin, including the book burnings on the square of the State Opera. Haftmann joined the Nazi party in 1937; the original typescript of his application for admission, stamped and approved in Wilmersdorf, the district I happen to live in, was on display in the summer and fall of 2021 at the Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin—and, as always, it’s difficult to understand how this information managed to remain hidden for over eighty years. Another recent discovery is evidence Italian historian Carlo Gentile found documenting that Haftmann, who had joined the Wehrmacht in 1940 and had been awarded medals for bravery several times, led a commando that hunted down and tortured Italian partisans and executed civilians.

Of course, Haftmann never spoke about his history; indeed, when he co-founded the first documenta in 1955, there was a considerable omission at its core. Curiously absent in the first major German exhibition of modern art in the post-war era were works of Jewish artists who had perished in the camps; also missing were the many artists who had directly addressed Nazi persecution. Because to show them, documenta would have been forced not to look ahead to Germany’s bright new future, but to confront the Holocaust and industrialized genocide, and this—it bears mentioning that 10 of the exhibition’s 21 founding members had belonged to the NSDAP—was something that all parties evidently wished to avoid. Instead, Haftmann, a documented war criminal who later became director of the New National Gallery in Berlin, was instrumental in mythologizing German painting, including the works of the expressionist Emil Nolde—transforming the vehement anti-Semite into a “good German” who had staunchly defied Nazi repression by entering into an “inner emigration.” Here, too, it took many years for the historical details of a whitewashed biography to emerge; his paintings of a sunny, flower-filled garden and waves breaking on the North Sea shore adorned Chancellor Angela Merkel’s offices up until 2019, when a suggestion was made to replace them with two works by Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, many of whose paintings had also been labeled “degenerate art,” seized, and destroyed. After various anti-Semitic remarks made on the part of the latter during WWI came to light, however, Merkel decided to leave the walls of her office white, opting not to borrow any more works from the collections of the Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz, at least for the time being.

The first documenta of 1955 showed works by Otto Dix, Paul Klee, and Max Beckmann, but also Josef Albers, Robert Delaunay, Kurt Schwitters, and Wassily Kandinsky: the exhibition’s aim was to both rehabilitate the German avant-garde and champion abstraction as the path to a new and modern future. Haftmann also included pieces by Purrmann and Roeder, both of whom had survived the war, while Rudolf Levy, whose name had been penciled in on a handwritten list of artists initially considered for participation and subsequently crossed out, was absent. It seems to have taken thirty years for Haftmann’s conscience to get the better of him: in 1986, in the volume Banned and Persecuted: Dictatorship of Art under Hitler, he dedicated a double-page spread to Levy’s work, describing him as an artist who had been “nearly, and unjustifiably forgotten” and whose works possessed a “joyous radiance so unusual among the expressionist torment of German exhibitions of the 1920s.” Or perhaps it was mere opportunism that had changed his mind. In any case, the fact that he himself had contributed to Levy’s obscurity in the three decades following the end of World War II is not something Haftmann mentions or offers any explanation for.

Werner Haftmann visited his former employer, the Kunsthistorisches Institut, several times throughout the war years; it’s difficult to believe that he didn’t encounter Levy during this time. The American art historian and collector Bernard Berenson dubbed him his “foolometer,” an ideal source of classified information; apparently, Haftmann had a loose tongue. Levy, thirty-seven years his senior, veteran of World War I and recipient of the Iron Cross, was arrested on December 12, 1943 and died on a transport to Auschwitz. His painting Fiamma, a portrait of a young woman with half-closed eyes, painted in luminous complementary colors one year before he was hauled away by the SS, was recently purchased by the Uffizi Galleries. In a letter to Purrmann, Emy Roeder describes the day Levy was arrested by two men posing as art collectors interested in his work: “The next morning, they came for his clothing, which they packed into a leather suitcase along with anything else of Levy’s that looked to be of value. A short time later, they were wearing Levy’s clothes, a sure sign that poor Rudolf wouldn’t be coming back. We sent him a lot of food in prison, but B. said that he hadn’t received anything. A small note explaining that they were going to be taken away early the next morning at 6 a.m. Help, Help, Help. That was the last we ever heard of him.”

Emy Roeder had grown close to Rudolf Levy, and as I stand in the corridor between the kitchen and the library, gazing out of a small window onto a brightly lit air shaft, I can’t help but think of her living in the same room as I am now, putting on a pot of coffee in the tiny kitchen and standing at this very window, waiting for the water to boil and wondering what the next weeks and months might bring. Levy was nearly seventy years of age when someone denounced him; by the time the Allies occupied Florence and imprisoned her as an enemy alien, Roeder was in her mid-fifties. I decide I need some fresh air and walk down to Piazza Santo Spirito to see the Palazzo Guadagni. I venture through a massive wooden door into the foyer and take a few pictures; when I return outside, I happen upon a single brass “Stumbling Stone,” one of the cobblestone-sized memorial plaques set into the street to commemorate victims of Nazi atrocity at their last place of residence. A website tells me that the ceremony for Rudolf Levy’s stone took place on January 18, a little over six weeks ago. On the top floor of the palazzo, where the Bandini sisters once ran their boardinghouse, is a three-star boutique hotel consisting of tastefully decorated rooms with frescoes and expensive-looking antique furniture. As I sit outside, scrolling through the website and wondering which room is the site of Levy’s former studio and the window from which he painted the Chiesa Santo Spirito, I watch passersby fail to notice the small brass-covered plaque. I decide to cross the square and have a look inside the church, where I sit at a distance from a small group of parishioners praying out loud. I try not to stare, but I’m transfixed by their voices intoning in unison; twice, I inadvertently catch the eye of an older man in the group, and decide it’s best if I keep my gaze fixed on the stone floor. Toward the end, I can make out prega per noi, prega per noi, prega per noi, pray for us, repeated over and over again, the refrain of the Litany of Loreto, a prayer to Mary, Mother of God. All at once, the man gets up from his pew and heads in my direction; he seems agitated, he’s talking now, and he’s directing his words at me. I tell him I don’t understand, because although I’m trying, I really don’t. He insists, points his finger, gestures at my seat. He seems to be looking for something, and I stand up, confused. I only realize that he thinks I’ve been hiding something when there’s nothing to be found on the pew beneath me. He seems unsatisfied, he grumbles something and wanders back to his little group, continues talking to a woman there, gesticulates. What has he lost, I wonder, and to signalize my good will I approach cautiously, questioningly, glancing around the rows of pews separating us, hoping to communicate a desire to help. The woman he is speaking to avoids my gaze. Prega per noi, I think, prega per noi, prega per noi, the refrain follows me all the way back to Porta Romana and up the hill of Via Senese as I wonder if the group was praying for Ukraine, or for themselves and their own sorrows.

***

© 2022 Andrea Scrima. All Rights Reserved.

Information on Andrea Scrima’s first novel, A Lesser Day, can be found here.

Her second novel, Like Lips, Like Skins, was published Sept. 2021 in a German edition titled Kreisläufe. English-language excerpts have appeared in Trafika Europe, Statorec, and Zyzzyva.

Part One of an interview with the author was published here on Three Quarks Daily, Part Two here.