David Serlin at Cabinet Magazine:

In Richard Fleischer’s 1966 film Fantastic Voyage, an elite crew of medical technicians—including the buxom but brainy Cora Peterson (Raquel Welch)—is shrunken down to microscopic size and climbs aboard the Proteus, a nano-sized submarine. The crew’s mission: to use a modified laser to destroy a blood clot on the brain of a dying scientist who holds important Cold War military secrets. Navigating their way through the dark, dangerous world of multicellular marauders and bacterial invaders, the crew of the Proteus spends a good amount of time on-screen peering out the windows in awe of the human body’s oceanic interior. Just after completing their assignment, and with valuable seconds ticking away, the crew of the Proteus is attacked by white blood cells. The survivors exit the body by riding out through a tear duct, cushioned in the saline safety of a single teardrop.

In Richard Fleischer’s 1966 film Fantastic Voyage, an elite crew of medical technicians—including the buxom but brainy Cora Peterson (Raquel Welch)—is shrunken down to microscopic size and climbs aboard the Proteus, a nano-sized submarine. The crew’s mission: to use a modified laser to destroy a blood clot on the brain of a dying scientist who holds important Cold War military secrets. Navigating their way through the dark, dangerous world of multicellular marauders and bacterial invaders, the crew of the Proteus spends a good amount of time on-screen peering out the windows in awe of the human body’s oceanic interior. Just after completing their assignment, and with valuable seconds ticking away, the crew of the Proteus is attacked by white blood cells. The survivors exit the body by riding out through a tear duct, cushioned in the saline safety of a single teardrop.

For all its retrospective camp value, Fantastic Voyage is also a fascinating cultural hybrid, the talented offspring of postwar American cinema and postwar American science.

more here.

Margaret Atwood, without a doubt one of the greatest living writers, is best known for her incredibly successful and award-winning novels The Handmaid’s Tale and, more recently, The Testaments. However, she is also an extraordinary short story writer — and Old Babes in the Wood, her first collection in almost a decade, is a dazzling mixture of stories that explore what it means to be human while also showcasing Atwood’s gifted imagination and great sense of humor.

Margaret Atwood, without a doubt one of the greatest living writers, is best known for her incredibly successful and award-winning novels The Handmaid’s Tale and, more recently, The Testaments. However, she is also an extraordinary short story writer — and Old Babes in the Wood, her first collection in almost a decade, is a dazzling mixture of stories that explore what it means to be human while also showcasing Atwood’s gifted imagination and great sense of humor. In July, Jennifer O’Brien got the phone call that adult children dread. Her 84-year-old father, who insisted on living alone in rural New Mexico, had broken his hip. The neighbor who found him on the floor after a fall had called an ambulance.

In July, Jennifer O’Brien got the phone call that adult children dread. Her 84-year-old father, who insisted on living alone in rural New Mexico, had broken his hip. The neighbor who found him on the floor after a fall had called an ambulance.

About a third of the way through a first-year humanities honors course, one of my more engaged and talkative students pulled me aside after class for a private chat. She waited, clearly anxious, while the rest of her classmates filed out and then turned to me with her eyes already filling up with tears.

About a third of the way through a first-year humanities honors course, one of my more engaged and talkative students pulled me aside after class for a private chat. She waited, clearly anxious, while the rest of her classmates filed out and then turned to me with her eyes already filling up with tears.

My father, the son of Italian immigrants, was a member of the working class. There were things within reach, and things that were not in reach, and he accepted this. He never pushed his children to broaden their horizons, and would have been satisfied to see them in traditional working-class vocations. When I came home from school eager to show off my grades, he poked fun at me. The prospect of pursuing an intellectual career was alien to him; in his view, taking out student loans to go to college or university was a way for banks to trap the “little guy.” When I presented him with the papers, he refused to sign. There was no discussion. I eventually moved out and managed to get my BFA anyway, and when I wound up as a finalist for a Fulbright, the doctor who performed the general checkup required by the awarding commission—I was still covered by my father’s Blue Cross plan, but only because I was still technically a dependent and it didn’t cost him anything—took him aside and told him that a Fulbright would be “quite a feather in your daughter’s cap.”

My father, the son of Italian immigrants, was a member of the working class. There were things within reach, and things that were not in reach, and he accepted this. He never pushed his children to broaden their horizons, and would have been satisfied to see them in traditional working-class vocations. When I came home from school eager to show off my grades, he poked fun at me. The prospect of pursuing an intellectual career was alien to him; in his view, taking out student loans to go to college or university was a way for banks to trap the “little guy.” When I presented him with the papers, he refused to sign. There was no discussion. I eventually moved out and managed to get my BFA anyway, and when I wound up as a finalist for a Fulbright, the doctor who performed the general checkup required by the awarding commission—I was still covered by my father’s Blue Cross plan, but only because I was still technically a dependent and it didn’t cost him anything—took him aside and told him that a Fulbright would be “quite a feather in your daughter’s cap.”

Sughra Raza. Just a Street Corner. Boston, 2022.

Sughra Raza. Just a Street Corner. Boston, 2022.

Mohammed Ali Jinnah’s Last Visit to Kashmir 10 May – 25 July 1944

Mohammed Ali Jinnah’s Last Visit to Kashmir 10 May – 25 July 1944

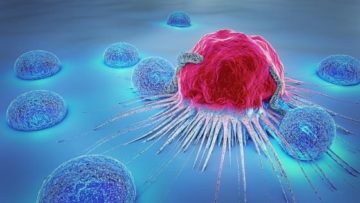

No metaphor for cancer does it justice. As a medical oncologist and cancer researcher, I struggle constantly with how people perceive cancer. Until a person suffers from it or sees a loved one suffer from the devastation of this disease, cancer remains an abstract term or concept. But it is an abstract concept that kills 10 million people around the world every year. Ten million people every year. How do we get people to understand that this is a lethal disease that deserves attention. That deserves more funding. That deserves more minds thinking about how to stop the continual suffering that metastatic cancer causes.

No metaphor for cancer does it justice. As a medical oncologist and cancer researcher, I struggle constantly with how people perceive cancer. Until a person suffers from it or sees a loved one suffer from the devastation of this disease, cancer remains an abstract term or concept. But it is an abstract concept that kills 10 million people around the world every year. Ten million people every year. How do we get people to understand that this is a lethal disease that deserves attention. That deserves more funding. That deserves more minds thinking about how to stop the continual suffering that metastatic cancer causes. There is something

There is something Researchers are discovering that “springing ahead” each March is connected with serious negative health effects, including an uptick in

Researchers are discovering that “springing ahead” each March is connected with serious negative health effects, including an uptick in