Month: March 2023

The Search For Traces Of A Beloved Writer

Patricia Hampl at The American Scholar:

She too was a link, though a precious one, the only living connection to the ghost I stalked. Katherine Mansfield. The romantic renegade writer, older by five years at her death at 34 in January 1923 than I was/am on this June day in 1975.

She too was a link, though a precious one, the only living connection to the ghost I stalked. Katherine Mansfield. The romantic renegade writer, older by five years at her death at 34 in January 1923 than I was/am on this June day in 1975.

My first “trip abroad” (a phrase then still common, oddly antique now). The journey from home in St. Paul had been made for this encounter, to interview Mansfield’s best friend, possibly a one-time lover, it was said—would the girl burdened with flowers and tape recorder nerve up to inquire about that ?

LM was the ancient leftover not only of their relationship, but of their world. She, Leslie Moore, had been coaxed into writing a memoir—Katherine Mansfield: The Memories of LM—by the man wearing the stiff boater. And now she had agreed to let “a young American” who had read her book meet its author for an interview.

more here.

Friday Poem

Next Year or Someday

I’ll see you at the Farmer’s Market

moving slowly through the crowd – there will

be a crowd then among the stalls, shoppers

touching tomatoes glowing earth-blood colors,

asking unmasked farmers about their climate-year.

On a festive day I’ll join you to watch

the Miwuk dancers stomp and spin, fringes

moving with the drums. Back in the time of masks,

we traded Columbus for Indigenous Peoples

Day. We brought Dia de los Muertos to the Market,

singers cloaking their fado-mariachi.

Back then, I wondered if it was infringement,

being outside our pod under sky

with the dancers chanting their songs, a flute

exhaling, everyone stirring the air to particulate

eddies of grief and joy. Beauty, love, life

always at risk. Isn’t that what grounds the ancient

songs? Next year or someday we’ll gather again

to celebrate what we’ve lived, lost, and found.

by Taylor Graham

from Poets Online

“The Elements of Utopia”: Nina Leen in California, 1945

From The Morning News:

California’s population growth was one of defining trends of 20th-century America. From 1900 to 1950 the population increased 500%, going from two million to ten million. Then things really exploded, and by the year 2000 the state’s population had climbed to 34 million, making California the most populous state in America. People have been lured west for a variety of reasons, from the gold rush to Hollywood dreams, but beyond riches and fame there has been also the promise of the sunny California lifestyle, one captured by LIFE staff photographer Nina Leen in a piece that ran in the Oct. 22, 1945 issue.

California’s population growth was one of defining trends of 20th-century America. From 1900 to 1950 the population increased 500%, going from two million to ten million. Then things really exploded, and by the year 2000 the state’s population had climbed to 34 million, making California the most populous state in America. People have been lured west for a variety of reasons, from the gold rush to Hollywood dreams, but beyond riches and fame there has been also the promise of the sunny California lifestyle, one captured by LIFE staff photographer Nina Leen in a piece that ran in the Oct. 22, 1945 issue.

The unreservedly enthusiastic thirteen-page essay was titled “The California Way of Life,” and it’s not hard to imagine that the article affected some readers the way news of gold in Sutter’s Mill did in the 1800s. The story began with these words, which could have come from a state tourist brochure:

Californians live in a land where the sun shines 355 days a year, where the thermometer seldom falls below 46 degrees, and where towering mountains and endless beaches flank a countryside of incredible fertility. Against the background of these unique natural advantages, Californians have evolved a unique way of life which is physically the most comfortable and attractive way of life enjoyed in any region in the U.S.

It’s worth noting that this story came out just a few short months after the end of World War II, a time when readers might thirst for a new beginning. (The issue also included a story an another feel-good imagination-tickler: “victory lingerie.”)

More here.

How Loneliness Reshapes the Brain

Marta Zaraska in Quanta Magazine:

Loneliness can be difficult to study empirically because it is entirely subjective. Social isolation, a related condition, is different — it’s an objective measure of how few relationships a person has. The experience of loneliness has to be self-reported, although researchers have developed tools such as the UCLA Loneliness Scale to help with assessing the depths of an individual’s feelings. From such work, it’s clear that the physical and psychological toll of loneliness across the globe is profound. In one survey, 22% of Americans and 23% of British people said they felt lonely always or often. And that was before the pandemic. As of October 2020, 36% of Americans reported “serious loneliness.”

Loneliness can be difficult to study empirically because it is entirely subjective. Social isolation, a related condition, is different — it’s an objective measure of how few relationships a person has. The experience of loneliness has to be self-reported, although researchers have developed tools such as the UCLA Loneliness Scale to help with assessing the depths of an individual’s feelings. From such work, it’s clear that the physical and psychological toll of loneliness across the globe is profound. In one survey, 22% of Americans and 23% of British people said they felt lonely always or often. And that was before the pandemic. As of October 2020, 36% of Americans reported “serious loneliness.”

As the researchers described in 2019, in comparison to a control group, the socially isolated team lost volume in their prefrontal cortex — the region at the front of the brain, just behind the forehead, that is chiefly responsible for decision-making and problem-solving. They also had lower levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, a protein that nurtures the development and survival of nerve cells in the brain. The reduction persisted for at least a month and a half after the team’s return from Antarctica.

More here.

The Hyperstitious Slur Cascade

Scott Alexander in Astral Codex Ten:

Someone asks: why is “Jap” a slur? It’s the natural shortening of “Japanese person”, just as “Brit” is the natural shortening of “British person”. Nobody says “Brit” is a slur. Why should “Jap” be?

Someone asks: why is “Jap” a slur? It’s the natural shortening of “Japanese person”, just as “Brit” is the natural shortening of “British person”. Nobody says “Brit” is a slur. Why should “Jap” be?

My understanding: originally it wasn’t a slur. Like any other word, you would use the long form (“Japanese person”) in dry formal language, and the short form (“Jap”) in informal or emotionally charged language. During World War II, there was a lot of informal emotionally charged language about Japanese people, mostly negative. The symmetry broke. Maybe “Japanese person” was used 60-40 positive vs. negative, and “Jap” was used 40-60. This isn’t enough to make a slur, but it’s enough to make a vague connotation. When people wanted to speak positively about the group, they used the slightly-more-positive-sounding “Japanese people”; when they wanted to speak negatively, they used the slightly-more-negative-sounding “Jap”.

At some point, someone must have commented on this explicitly: “Consider not using the word ‘Jap’, it makes you sound hostile”. Then anyone who didn’t want to sound hostile to the Japanese avoided it, and anyone who did want to sound hostile to the Japanese used it more. We started with perfect symmetry: both forms were 50-50 positive negative. Some chance events gave it slight asymmetry: maybe one form was 60-40 negative. Once someone said “That’s a slur, don’t use it”, the symmetry collapsed completely and it became 95-5 or something.

More here.

UN forges historic deal to protect ocean life

Nicola Jones in Nature:

After years of debates and discussions, nations have agreed on a High Seas Treaty to protect marine biodiversity and provide oversight of international waters. It is being lauded by researchers as an important step for conservation that encourages international research collaboration without hindering science.

After years of debates and discussions, nations have agreed on a High Seas Treaty to protect marine biodiversity and provide oversight of international waters. It is being lauded by researchers as an important step for conservation that encourages international research collaboration without hindering science.

“We’re ecstatic,” says Kristina Gjerde, who researches marine environmental law at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies in Monterey, California. “This long-awaited treaty contains many of the vital things we need to safeguard our oceans.”

The final wording of the agreement was hashed out by delegates of the United Nations Intergovernmental Conference on Marine Biodiversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) at the end of a two-week meeting in New York City.

More here.

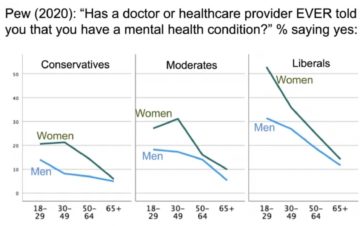

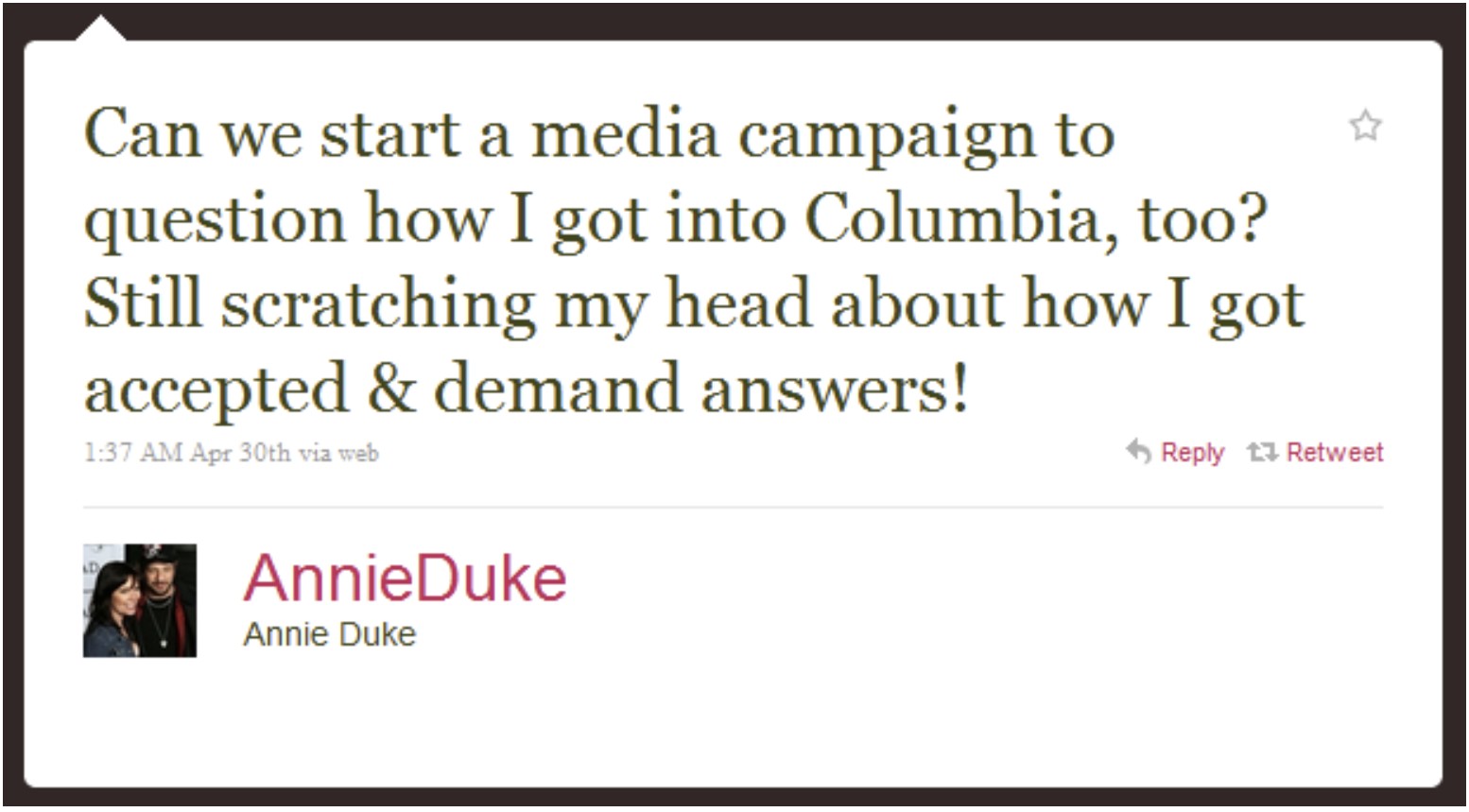

Why the Mental Health of Liberal Girls Sank First and Fastest

Jonathan Haidt in After Babel:

In May 2014, Greg Lukianoff invited me to lunch to talk about something he was seeing on college campuses that disturbed him. Greg is the president of FIRE (the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression), and he has worked tirelessly since 2001 to defend the free speech rights of college students. That almost always meant pushing back against administrators who didn’t want students to cause trouble, and who justified their suppression of speech with appeals to the emotional “safety” of students—appeals that the students themselves didn’t buy. But in late 2013, Greg began to encounter new cases in which students were pushing to ban speakers, punish people for ordinary speech, or implement policies that would chill free speech. These students arrived on campus in the fall of 2013 already accepting the idea that books, words, and ideas could hurt them. Why did so many students in 2013 believe this, when there was little sign of such beliefs in 2011?

In May 2014, Greg Lukianoff invited me to lunch to talk about something he was seeing on college campuses that disturbed him. Greg is the president of FIRE (the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression), and he has worked tirelessly since 2001 to defend the free speech rights of college students. That almost always meant pushing back against administrators who didn’t want students to cause trouble, and who justified their suppression of speech with appeals to the emotional “safety” of students—appeals that the students themselves didn’t buy. But in late 2013, Greg began to encounter new cases in which students were pushing to ban speakers, punish people for ordinary speech, or implement policies that would chill free speech. These students arrived on campus in the fall of 2013 already accepting the idea that books, words, and ideas could hurt them. Why did so many students in 2013 believe this, when there was little sign of such beliefs in 2011?

More here.

AlphaGo, The Movie: Full award-winning documentary

Thursday Poem

At Banagher

Then all of a sudden there appears to me

The journeyman tailor who was my antecedent:

Up on a table, cross-legged, ripping out

A garment he must recut or resew,

His lips tight back, a thread between his teeth,

Keeping his counsel always, giving none,

His eyelids steady as wrinkled horn or iron.

Self-absenting, both migrant and ensconced;

Admitted into kitchens, into clothes

His touch has the power to turn to cloth again—

All of a sudden he appears to me,

Unopen, unmendacious, unillumined.

………………………………… *

So more power to him on the job there, ill at ease

Under my scrutiny in spite of years

Of being inscrutable as he threaded needles

Or matched the facings, linings, hems and seams.

He holds the needle just off center, squinting,

And licks the thread and licks and sweeps it through,

Then takes his time to draw both threads out even,

Plucking them sharply twice. Then back to stitching.

Does he ever question what it all amounts to?

Or ever will? Or care where he lays his head?

My Lord Buddha of Banagher, the way

Is opener for you being in it.

by Seamus Heaney

from The Spirit Level

Dr. Ben Goertzel – Artificial General Intelligence

Bringing The Illiad Into Arabic

Suleiman Al-Bustani at The Baffler:

UNTIL THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, The Iliad had only been translated into European languages. By 1914, however, the situation had changed. Suleiman Al-Bustani’s 1904 Arabic version was just one among many translations into non-European languages—Armenian, Bengali, Urdu, Turkish, Gujrati, and Marathi, among others. This sudden interest in an ancient Greek epic poem might be understood from an anti-colonial perspective. It reflects the belief, held by many intellectuals of the period, that the symbolic power of Homer could be used to resist European claims to authority in an era of imperial expansion. If Homer’s epic is born, as Bustani argues, of the four corners of the world, the principle so central to Western Europe’s “civilizing mission”—that the ideas of Ancient Greece are the cultural foundation of the Christian West—loses some legitimacy.

UNTIL THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, The Iliad had only been translated into European languages. By 1914, however, the situation had changed. Suleiman Al-Bustani’s 1904 Arabic version was just one among many translations into non-European languages—Armenian, Bengali, Urdu, Turkish, Gujrati, and Marathi, among others. This sudden interest in an ancient Greek epic poem might be understood from an anti-colonial perspective. It reflects the belief, held by many intellectuals of the period, that the symbolic power of Homer could be used to resist European claims to authority in an era of imperial expansion. If Homer’s epic is born, as Bustani argues, of the four corners of the world, the principle so central to Western Europe’s “civilizing mission”—that the ideas of Ancient Greece are the cultural foundation of the Christian West—loses some legitimacy.

These translations were also far more than responses to Europe. For Bustani, The Iliad represented an inquiry into the Jahiliya of the Greeks: the period in Greek history that corresponds to the period in Arab history marked by the absence of divine guidance, prior to the revelation of the Quran.

more here.

On George Balanchine’s Vienna Waltzes

Laura Jacobs at The New Criterion:

The map of Balanchine’s life once he left Russia in 1924 and until he finally settled into the New York City Ballet in 1948 may read as a kind of wandering, but his life as an artist was made of circles: the revolving of the repertory, the return to old ballets, the rethinking and recalibration of steps and phrases. To the dismay of his audience, for instance, Balanchine pared back the iconic Apollon musagète, his breakthrough of 1928. Again and again he rechoreographed Stravinsky’s Le Baiser de la fée (based on heartbroken melodies by Tchaikovsky), trying to find the right form for its story of a child kissed into art and thus frozen out of a normal life—his story. And despite the astonishing breadth of his repertory, it was dominated by what one might call the waltz step of desire–love–loss. In fact, this was a vortex Balanchine needed. The centrifugal pull of the waltz, its three-four time as self-generating as the tide, rolling and turning, drawing one in and under, was pure energy.

The map of Balanchine’s life once he left Russia in 1924 and until he finally settled into the New York City Ballet in 1948 may read as a kind of wandering, but his life as an artist was made of circles: the revolving of the repertory, the return to old ballets, the rethinking and recalibration of steps and phrases. To the dismay of his audience, for instance, Balanchine pared back the iconic Apollon musagète, his breakthrough of 1928. Again and again he rechoreographed Stravinsky’s Le Baiser de la fée (based on heartbroken melodies by Tchaikovsky), trying to find the right form for its story of a child kissed into art and thus frozen out of a normal life—his story. And despite the astonishing breadth of his repertory, it was dominated by what one might call the waltz step of desire–love–loss. In fact, this was a vortex Balanchine needed. The centrifugal pull of the waltz, its three-four time as self-generating as the tide, rolling and turning, drawing one in and under, was pure energy.

more here.

The fear and fury of these Florida parents

Caitlin Gibson in The Washington Post:

In a nearby community in central Florida, Barbara Mellen attended a recent open house at her son’s elementary school and asked her child’s teacher to suggest a few titles or authors that might help her second-grader develop more interest in reading. The teacher looked anxious, she says, and told her he couldn’t recommend any books.

In the Facebook group Brittany Minor created five years ago for Black mothers like herself in Orlando, discussions among the 2,800 members have reached new depths of frustration and fatigue. These moms are watching what is happening in Florida, the shifting of the political and cultural environment around them, “and they are tired, they feel helpless, they feel hopeless,” Minor says. “The common thread is that people feel broken.”

More here.

What Plants Are Saying About Us

Amanda Gefter in Nautilus:

I was never into house plants until I bought one on a whim—a prayer plant, it was called, a lush, leafy thing with painterly green spots and ribs of bright red veins. The night I brought it home I heard a rustling in my room. Had something scurried? A mouse? Three jumpy nights passed before I realized what was happening: The plant was moving. During the day, its leaves would splay flat, sunbathing, but at night they’d clamber over one another to stand at attention, their stems steadily rising as the leaves turned vertical, like hands in prayer.

I was never into house plants until I bought one on a whim—a prayer plant, it was called, a lush, leafy thing with painterly green spots and ribs of bright red veins. The night I brought it home I heard a rustling in my room. Had something scurried? A mouse? Three jumpy nights passed before I realized what was happening: The plant was moving. During the day, its leaves would splay flat, sunbathing, but at night they’d clamber over one another to stand at attention, their stems steadily rising as the leaves turned vertical, like hands in prayer.

“Who knew plants do stuff?” I marveled. Suddenly plants seemed more interesting. When the pandemic hit, I brought more of them home, just to add some life to the place, and then there were more, and more still, until the ratio of plants to household surfaces bordered on deranged. Bushwhacking through my apartment, I worried whether the plants were getting enough water, or too much water, or the right kind of light—or, in the case of a giant carnivorous pitcher plant hanging from the ceiling, whether I was leaving enough fish food in its traps. But what never occurred to me, not even once, was to wonder what the plants were thinking.

More here.

Robert Pinsky on “True Life,” a collection of verse by the Polish poet Adam Zagajewski

Robert Pinsky in the New York Times:

The Polish poet Adam Zagajewski’s great poem “To Go to Lvov” has a special importance for many young poets in different languages. That poem weaves the historical and the personal, the rhythms of cataclysm and of ordinary life, loss and persistence, all embodied in Zagajewski’s native city. “To Go to Lvov” has provided a model — intensely local, adamantly not nationalistic — for poems rooted in Philadelphia, Buenos Aires and Lahore.

The Polish poet Adam Zagajewski’s great poem “To Go to Lvov” has a special importance for many young poets in different languages. That poem weaves the historical and the personal, the rhythms of cataclysm and of ordinary life, loss and persistence, all embodied in Zagajewski’s native city. “To Go to Lvov” has provided a model — intensely local, adamantly not nationalistic — for poems rooted in Philadelphia, Buenos Aires and Lahore.

The Polish pronunciation and spelling Lvov has been replaced by the Ukrainian Lviv, and behind it the linguistic and cultural echoes of Lwow and Lemberg, in an involved, blood-determined pageant of related but different names for the place. That ongoing story makes Zagajewski’s poem of shared, discordant layers of loss and persistence feel all the more poignant, and the more urgently relevant, since the invasion of Ukraine by the Putin regime, with its war crimes against an entire population.

More here.

AI creates pictures of what people are seeing by analysing brain scans

Carissa Wong in New Scientist:

A tweak to a popular text-to-image-generating artificial intelligence allows it to turn brain signals directly into pictures. The system requires extensive training using bulky and costly imaging equipment, however, so everyday mind reading is a long way from reality.

Several research groups have previously generated images from brain signals using energy-intensive AI models that require fine-tuning of millions to billions of parameters.

Now, Shinji Nishimoto and Yu Takagi at Osaka University in Japan have developed a much simpler approach using Stable Diffusion, a text-to-image generator released by Stability AI in August 2022. Their new method involves thousands, rather than millions, of parameters.

More here.

GPT 5 is All About Data

The Evolution of Social Paradoxes

David Pinsof in PsyArXiv Preprints:

Human behavior is often paradoxical. We show humility to prove we’re better than other people, we bravely defy social norms so that people will praise us, and we donate to charity anonymously to get credit for not caring about getting credit. Here, I argue that these and other social paradoxes have a common thread: they are all attempts to signal a trait while concealing the fact that one is signaling the trait. Such self-negating signals emerge from the interaction of two cognitive abilities: 1) cue-based inference, and 2) recursive mentalizing. If agents can model each other’s mental states, including their intentions to signal positive traits, then intentional signals of positive traits can, themselves, become cues of negative traits. The result is that status-seeking and virtue-signaling are forced to occur covertly, without becoming common knowledge among signalers or recipients. Social paradoxes also play a crucial role in enabling intergroup dominance by inhibiting common knowledge of the group’s dominance-seeking tactics, which would otherwise disrupt coordination by eliciting moral disapproval. The analysis of social paradoxes can explain a variety of puzzling aspects of human social life, including the cultural evolution of status symbols, the function of sacred values, and the nature of political belief systems.

Human behavior is often paradoxical. We show humility to prove we’re better than other people, we bravely defy social norms so that people will praise us, and we donate to charity anonymously to get credit for not caring about getting credit. Here, I argue that these and other social paradoxes have a common thread: they are all attempts to signal a trait while concealing the fact that one is signaling the trait. Such self-negating signals emerge from the interaction of two cognitive abilities: 1) cue-based inference, and 2) recursive mentalizing. If agents can model each other’s mental states, including their intentions to signal positive traits, then intentional signals of positive traits can, themselves, become cues of negative traits. The result is that status-seeking and virtue-signaling are forced to occur covertly, without becoming common knowledge among signalers or recipients. Social paradoxes also play a crucial role in enabling intergroup dominance by inhibiting common knowledge of the group’s dominance-seeking tactics, which would otherwise disrupt coordination by eliciting moral disapproval. The analysis of social paradoxes can explain a variety of puzzling aspects of human social life, including the cultural evolution of status symbols, the function of sacred values, and the nature of political belief systems.

More here.

One afternoon a few weeks ago, Alicea Hotchkiss’s 14-year-old son, Eli, came home from his high school in Tampa with a question about something a classmate had said to him. He’d heard the student use the word “gay” as an insult, so Eli responded the way he always does when this happens. “Hey,” Eli said, “my dad’s gay.” But this time, Eli told his mom, the other kid offered a startling rebuke: You’re not allowed to say that at school.

One afternoon a few weeks ago, Alicea Hotchkiss’s 14-year-old son, Eli, came home from his high school in Tampa with a question about something a classmate had said to him. He’d heard the student use the word “gay” as an insult, so Eli responded the way he always does when this happens. “Hey,” Eli said, “my dad’s gay.” But this time, Eli told his mom, the other kid offered a startling rebuke: You’re not allowed to say that at school.