Yuval Noah Harari in Haaretz:

A “coup from above” occurs when a government that came to power in a perfectly legal way, violates the restrictions the law imposes on it, and tries to gain unlimited power. It’s a very old trick: First use the law to gain power, then use power to distort the law.

A “coup from above” occurs when a government that came to power in a perfectly legal way, violates the restrictions the law imposes on it, and tries to gain unlimited power. It’s a very old trick: First use the law to gain power, then use power to distort the law.

It can be very confusing when a “coup from above” takes place. On the face of it, everything looks normal. There are no tanks in the streets, and no general with a uniform sagging with medals interrupts the television broadcasts. The coup occurs behind closed doors, with laws being passed and decrees being signed that remove all restraints on the government, and dismantle all checks and balances. Of course, the government does not declare that it is carrying out a coup. It claims only that it is passing some much-needed reforms, “for the good of the people.”

How can we in Israel today determine whether we are facing a genuine reform or a coup? The simplest test is to ask: Are there still limits on the power of the government?

More here.

Sure, we’re a website about books, but that doesn’t mean we can’t get in on the Oscars fun, too. (Exhibit A: If they gave Oscars to books,

Sure, we’re a website about books, but that doesn’t mean we can’t get in on the Oscars fun, too. (Exhibit A: If they gave Oscars to books,  W

W Intelligent decision-making doesn’t require a brain. You were capable of it before you even had one. Beginning life as a single fertilised egg, you divided and became a mass of genetically identical cells. They chattered among themselves to fashion a complex anatomical structure – your body. Even more remarkably, if you had split in two as an embryo, each half would have been able to replace what was missing, leaving you as one of two identical (monozygotic) twins. Likewise, if two mouse embryos are mushed together like a snowball, a single, normal mouse results. Just how do these embryos know what to do? We have no technology yet that has this degree of plasticity – recognising a deviation from the normal course of events and responding to achieve the same outcome overall.

Intelligent decision-making doesn’t require a brain. You were capable of it before you even had one. Beginning life as a single fertilised egg, you divided and became a mass of genetically identical cells. They chattered among themselves to fashion a complex anatomical structure – your body. Even more remarkably, if you had split in two as an embryo, each half would have been able to replace what was missing, leaving you as one of two identical (monozygotic) twins. Likewise, if two mouse embryos are mushed together like a snowball, a single, normal mouse results. Just how do these embryos know what to do? We have no technology yet that has this degree of plasticity – recognising a deviation from the normal course of events and responding to achieve the same outcome overall. Anton Jäger in The Point:

Anton Jäger in The Point: Seymour Hersh in Jacobin:

Seymour Hersh in Jacobin: Aditya Bahl in Sidecar:

Aditya Bahl in Sidecar: This month marks seven years since the unexpected passing of the British-Iraqi architect Zaha Hadid, at what was undoubtedly the height of her historic career. Her influence on international architecture can’t be overstated. She was part of a generation of architects who both redefined and invented the forms that would characterize contemporary design. And as an Arab woman garnering international fame, she challenged “who” an architect could be.

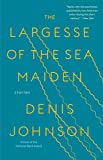

This month marks seven years since the unexpected passing of the British-Iraqi architect Zaha Hadid, at what was undoubtedly the height of her historic career. Her influence on international architecture can’t be overstated. She was part of a generation of architects who both redefined and invented the forms that would characterize contemporary design. And as an Arab woman garnering international fame, she challenged “who” an architect could be. Johnson, who died in 2017, was a National Book Award winner, two-time Pulitzer finalist, and the recipient of the Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction. George Saunders called him “Our most poetic American short-story writer since Hemingway.” It’s therefore curious that, despite wide recognition within the world of letters, Johnson’s renown hasn’t crossed into household lexicon in the manner of some recent greats (Egan, Whitehead, Franzen).

Johnson, who died in 2017, was a National Book Award winner, two-time Pulitzer finalist, and the recipient of the Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction. George Saunders called him “Our most poetic American short-story writer since Hemingway.” It’s therefore curious that, despite wide recognition within the world of letters, Johnson’s renown hasn’t crossed into household lexicon in the manner of some recent greats (Egan, Whitehead, Franzen). The U.S. is a powerhouse in technology, so it’s no surprise that the biggest success in the medical field has been technology based. Medicine in the U.S. is a powerful engine of creation, with more clinical trials and more medical start-ups than any other country. If you need a treatment for a rare disease, or heart transplant surgery, or cancer immunotherapy, the U.S. is the best place to be—it is the center of cutting-edge technologies and procedures. But the trend towards faster, better and cheaper that characterizes the evolution of technology has not translated to health care, which each year seems to get more cumbersome, expensive and, especially considering the recent fall in life expectancy during the pandemic, worse in terms of outcomes.

The U.S. is a powerhouse in technology, so it’s no surprise that the biggest success in the medical field has been technology based. Medicine in the U.S. is a powerful engine of creation, with more clinical trials and more medical start-ups than any other country. If you need a treatment for a rare disease, or heart transplant surgery, or cancer immunotherapy, the U.S. is the best place to be—it is the center of cutting-edge technologies and procedures. But the trend towards faster, better and cheaper that characterizes the evolution of technology has not translated to health care, which each year seems to get more cumbersome, expensive and, especially considering the recent fall in life expectancy during the pandemic, worse in terms of outcomes. There’s a moment deep in the Marquis de Sade’s novel “120 Days of Sodom” when a libertine laments the numbness of having committed every possible debauchery. “How many times, by God, have I not longed to be able to assail the sun, snatch it out of the universe, make a general darkness or use that star to burn the world!” The most destructive binge has limits, he realizes. Just knowing that will dampen the best sadistic orgy.

There’s a moment deep in the Marquis de Sade’s novel “120 Days of Sodom” when a libertine laments the numbness of having committed every possible debauchery. “How many times, by God, have I not longed to be able to assail the sun, snatch it out of the universe, make a general darkness or use that star to burn the world!” The most destructive binge has limits, he realizes. Just knowing that will dampen the best sadistic orgy. In Hound of the Baskervilles (1902) by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Sherlock Holmes examines a note written on a snippet from The Times. He concludes its author was an « educated man who wished to pose as an uneducated one, and his effort to conceal his own writing suggests that that writing might be known. » Dr. Mortimer calls it guesswork, but Holmes disagrees: « It is the scientific use of the imagination. »

In Hound of the Baskervilles (1902) by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Sherlock Holmes examines a note written on a snippet from The Times. He concludes its author was an « educated man who wished to pose as an uneducated one, and his effort to conceal his own writing suggests that that writing might be known. » Dr. Mortimer calls it guesswork, but Holmes disagrees: « It is the scientific use of the imagination. » Researchers have made eggs from the cells of male mice — and showed that, once fertilized and implanted into female mice, the eggs can develop into seemingly healthy, fertile offspring.

Researchers have made eggs from the cells of male mice — and showed that, once fertilized and implanted into female mice, the eggs can develop into seemingly healthy, fertile offspring.

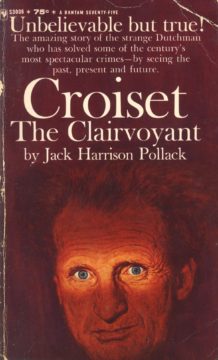

I would like to focus on a special way of predicting the future, and to invite you to take a trip down paths that are rarely trodden by humanists. As we are living at a time of unusual uncertainty and anxiety about what will happen next, this topic is on many people’s minds, prompting us to ask: “What is our future going to be like?” And also: “Can we foresee it to any degree at all?” When I say “our future” I’m not thinking of the next few years, but rather about the gradual processes whose effects will be visible several centuries from now.

I would like to focus on a special way of predicting the future, and to invite you to take a trip down paths that are rarely trodden by humanists. As we are living at a time of unusual uncertainty and anxiety about what will happen next, this topic is on many people’s minds, prompting us to ask: “What is our future going to be like?” And also: “Can we foresee it to any degree at all?” When I say “our future” I’m not thinking of the next few years, but rather about the gradual processes whose effects will be visible several centuries from now.