Daisuke Wakabayashi in The New York Times:

The mission to turn space into the next frontier for express deliveries took off from a modest propeller plane above a remote airstrip in the shadow of the Santa Ana mountains. Shortly after sunrise on a recent Saturday, an engineer for Inversion Space, a start-up that’s barely a year old, tossed a capsule resembling a flying saucer out the open door of an aircraft flying at 3,000 feet. The capsule, 20 inches in diameter, somersaulted in the air for a few seconds before a parachute deployed and snapped the container upright for a slow descent. “It was slow to open,” said Justin Fiaschetti, Inversion’s 23-year-old chief executive, who anxiously watched the parachute through the viewfinder of a camera with a long lens.

The mission to turn space into the next frontier for express deliveries took off from a modest propeller plane above a remote airstrip in the shadow of the Santa Ana mountains. Shortly after sunrise on a recent Saturday, an engineer for Inversion Space, a start-up that’s barely a year old, tossed a capsule resembling a flying saucer out the open door of an aircraft flying at 3,000 feet. The capsule, 20 inches in diameter, somersaulted in the air for a few seconds before a parachute deployed and snapped the container upright for a slow descent. “It was slow to open,” said Justin Fiaschetti, Inversion’s 23-year-old chief executive, who anxiously watched the parachute through the viewfinder of a camera with a long lens.

The exercise looked like the work of amateur rocketry enthusiasts. But, in fact, it was a test run for something more fantastical. Inversion is building earth-orbiting capsules to deliver goods anywhere in the world from outer space. To make that a reality, Inversion’s capsule will come through the earth’s atmosphere at about 25 times as fast as the speed of sound, making the parachute essential for a soft landing and undisturbed cargo.

More here.

The heliostats will reflect the sun’s rays onto a tall, mirror-covered tower to be set in the center of town. In turn, the tower will deflect the light onto other mirrors mounted on building facades, diffusing the beams to prevent dangerously focused, scorching rays. The mirrors will not drench the town in an even, blinding glare; this is no movie set where, with the flip of a switch and a dozen flood bulbs, night dazzlingly becomes day. (Such broad, total illumination would require impossibly enormous mirrors.) Instead, light will cascade down to create areas of illumination, or “hotspots.” Preliminary sketches reveal a pleasantly dappled effect, not unlike the sun-speckled lanes of Thomas Kinkade paintings. These bright spots, however, will be about “lawn size,” large enough for people to cluster inside, like fish schooling in shimmering pools of sunshine.

The heliostats will reflect the sun’s rays onto a tall, mirror-covered tower to be set in the center of town. In turn, the tower will deflect the light onto other mirrors mounted on building facades, diffusing the beams to prevent dangerously focused, scorching rays. The mirrors will not drench the town in an even, blinding glare; this is no movie set where, with the flip of a switch and a dozen flood bulbs, night dazzlingly becomes day. (Such broad, total illumination would require impossibly enormous mirrors.) Instead, light will cascade down to create areas of illumination, or “hotspots.” Preliminary sketches reveal a pleasantly dappled effect, not unlike the sun-speckled lanes of Thomas Kinkade paintings. These bright spots, however, will be about “lawn size,” large enough for people to cluster inside, like fish schooling in shimmering pools of sunshine. The word “salon,” for a starry convocation of creative types, intelligentsia, and patrons, has never firmly penetrated English. It retains a pair of transatlantic wet feet from the phenomenon’s storied annals, chiefly in France, since the eighteenth century. So it was that the all-time most glamorous and consequential American instance, thriving in New York between 1915 and 1920, centered on Europeans in temporary flight from the miseries of the First World War. Their hosts were Walter Arensberg, a Pittsburgh steel heir, and his wife, Louise Stevens, an even wealthier Massachusetts textile-industry legatee. The couple had been thunderstruck by the 1913 Armory Show of international contemporary art, which exposed Americans to Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and, in particular, Marcel Duchamp. Made the previous year, his painting “Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2),” a cunning mashup of Cubism and Futurism, with its title hand-lettered along the bottom, was the event’s prime sensation: at once insinuating indecency and making it hard to perceive, what with the image’s scalloped planes, which a Times critic jovially likened to “an explosion in a shingle factory.”

The word “salon,” for a starry convocation of creative types, intelligentsia, and patrons, has never firmly penetrated English. It retains a pair of transatlantic wet feet from the phenomenon’s storied annals, chiefly in France, since the eighteenth century. So it was that the all-time most glamorous and consequential American instance, thriving in New York between 1915 and 1920, centered on Europeans in temporary flight from the miseries of the First World War. Their hosts were Walter Arensberg, a Pittsburgh steel heir, and his wife, Louise Stevens, an even wealthier Massachusetts textile-industry legatee. The couple had been thunderstruck by the 1913 Armory Show of international contemporary art, which exposed Americans to Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and, in particular, Marcel Duchamp. Made the previous year, his painting “Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2),” a cunning mashup of Cubism and Futurism, with its title hand-lettered along the bottom, was the event’s prime sensation: at once insinuating indecency and making it hard to perceive, what with the image’s scalloped planes, which a Times critic jovially likened to “an explosion in a shingle factory.” Vladimir Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine is clearly a historically momentous event, already appearing to cause a seismic shift in the geopolitical landscape. What the long-term consequences will be are hard to say. The most obvious losers are the millions of Ukrainians–killed, injured, bereft, and displaced–who are the immediate victims of Putin’s onslaught. The most likely winner will probably be China, on whom Russia is suddenly much more economically dependent due to the sanctions imposed by the West, and who can therefore now expect Putin to dance to whatever tune it whistles.

Vladimir Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine is clearly a historically momentous event, already appearing to cause a seismic shift in the geopolitical landscape. What the long-term consequences will be are hard to say. The most obvious losers are the millions of Ukrainians–killed, injured, bereft, and displaced–who are the immediate victims of Putin’s onslaught. The most likely winner will probably be China, on whom Russia is suddenly much more economically dependent due to the sanctions imposed by the West, and who can therefore now expect Putin to dance to whatever tune it whistles. The Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle (Workshop of Potential Literature), Oulipo for short, is the name of a group of primarily French writers, mathematicians, and academics that explores the use of mathematical and quasi-mathematical techniques in literature. Don’t let this description scare you. The results are often amusing, strange, and thought-provoking.

The Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle (Workshop of Potential Literature), Oulipo for short, is the name of a group of primarily French writers, mathematicians, and academics that explores the use of mathematical and quasi-mathematical techniques in literature. Don’t let this description scare you. The results are often amusing, strange, and thought-provoking. Despite living here for nearly three years now, I have no social life to speak of. At risk of sounding self-loathing, a not insignificant part of the problem is probably just me: I’m not the most social person in the world. Plus, there’s the pandemic, which hit six months after we moved here. But I don’t think it’s just me, or even just the pandemic. An awful lot of people who moved here as adults, decades ago, and are much nicer and more sociable than I am, have said the same thing: making friends in Toronto is hard.

Despite living here for nearly three years now, I have no social life to speak of. At risk of sounding self-loathing, a not insignificant part of the problem is probably just me: I’m not the most social person in the world. Plus, there’s the pandemic, which hit six months after we moved here. But I don’t think it’s just me, or even just the pandemic. An awful lot of people who moved here as adults, decades ago, and are much nicer and more sociable than I am, have said the same thing: making friends in Toronto is hard.

Sughra Raza. Self-portrait With Trees. Seattle, February, 2022.

Sughra Raza. Self-portrait With Trees. Seattle, February, 2022.

On 4 October 1957, in my mind’s eye, I was playing alone in the back yard when the radio in the breezeway broadcast a special news bulletin that changed my life. We had moved from Chicago to Minneapolis in 1951 and my parents had bought a recently built house on a dead-end street in a relatively cheap residential area out near the airport. The house was built in the modern suburban style that people called a ranch-style bungalow and its most interesting post-war feature was the breezeway, a screened-in patio attached to the house. The screens that kept flies and mosquitos at bay in warm weather were swapped for glass panels when the weather turned cold and we changed our window screens for storm widows.

On 4 October 1957, in my mind’s eye, I was playing alone in the back yard when the radio in the breezeway broadcast a special news bulletin that changed my life. We had moved from Chicago to Minneapolis in 1951 and my parents had bought a recently built house on a dead-end street in a relatively cheap residential area out near the airport. The house was built in the modern suburban style that people called a ranch-style bungalow and its most interesting post-war feature was the breezeway, a screened-in patio attached to the house. The screens that kept flies and mosquitos at bay in warm weather were swapped for glass panels when the weather turned cold and we changed our window screens for storm widows.

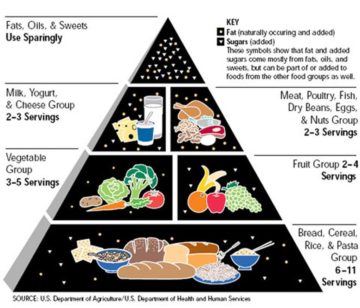

We have many choices when deciding what to eat. For most of human history, however, there has likely been little to no choice at all: people ate what was available to them or what their culture led them to eat. Now things are not so simple. As I mentioned in

We have many choices when deciding what to eat. For most of human history, however, there has likely been little to no choice at all: people ate what was available to them or what their culture led them to eat. Now things are not so simple. As I mentioned in