by Omar Baig

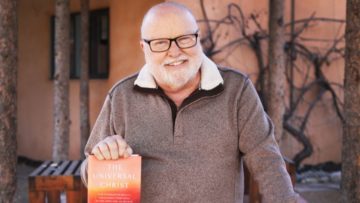

Conservative and Evangelical Christians—with their provincial notions of Jesus as dying on the cross for their sins—denounce the Cosmic Christ of Father Richard Rohr as new age heresy. Yet some Christians may not even realize that Jesus and Christ are not the same. As if, he jokes, Christ was simply the last name of Jesus. By building off the Franciscan mysticism he was ordained in, Fr. Rohr defends the “alternative orthodoxy” of an eternal Christ, through which material reality fully coincides with the spiritual. Bible verses like Colossians 1:17-20 portray Christ as “before all things,” including the Jesus of Nazareth, since “in Him all things hold together.” Ephesians 1:13 affirms our “inherent union” with Christ, for “you too have been stamped with the seal of the Holy Spirit.”

Over three decades of accusations—as an apostate, false prophet, or wolf in sheep’s clothing—have compelled Fr. Rohr to ground his seemingly unorthodox and progressive theological views with extensive biblical scripture and scholarly references. Despite a formal investigation by the Vatican, Rohr remains a priest in good standing with the Catholic Church. Scrutiny only bolsters his belief that one must first know the rules well enough before knowing when they do not apply. Like the cosmos itself, the Jesus of the gospel affirms two parallel drives toward diversity and communion. Rohr’s 1999 essay, “Where The Gospel Leads Us,” for example, extends God’s unconditional love to the whole of creation: since all relationships, including LGBT ones, demand “truth, faithfulness, and striving to enter into covenants of continuing forgiveness of one another.”

Yet most will never move beyond Ken Wilbur’s first stage of spiritual development, which is preoccupied with cleaning up their own self-image as a Good Christian. They judge, put down, and exclude others for their differing practices or views as Bad Christians. Rigid purity codes generate the respectability politics of each church by policing their member’s social behavior and determining their relative standing. This parallels the ego-formation and social conformity of early childhood development, when our sense as an individual separates from our sense of others. But defining yourself by who you aren’t is what led to the extreme polarization of our current politics. Each identity group seems to define themselves more by what they think is wrong with other groups, rather than rally around their shared beliefs or goals. Read more »

I enjoyed my days in Delhi School of Economics, but some aspects of the university’s policy in recruitment and promotion of teachers used to trouble me. Let me just give two examples. One is from DSE itself, but illustrative of a much more general problem in university life. We had a middle-aged colleague who had long wanted to be promoted to Readership (Associate Professorship), but failed in the usual process, because he had not done any serious research to speak of in many years. He was full of leftist clichés, and was popular with some sections of leftist students. He first started complaining that he was being passed over in promotion because his ‘right-wing’ colleagues (the term used in Economics those days was ‘neo-classical’—in the same pejorative way the term ‘neo-liberal’ is used nowadays) were biased in undervaluing his work. This after a time did not work, as even some leftist scholars in the Department shared views similar to those of the ‘right-wing’ colleagues on this matter. Then he tried a different tack.

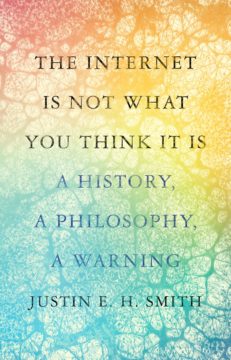

I enjoyed my days in Delhi School of Economics, but some aspects of the university’s policy in recruitment and promotion of teachers used to trouble me. Let me just give two examples. One is from DSE itself, but illustrative of a much more general problem in university life. We had a middle-aged colleague who had long wanted to be promoted to Readership (Associate Professorship), but failed in the usual process, because he had not done any serious research to speak of in many years. He was full of leftist clichés, and was popular with some sections of leftist students. He first started complaining that he was being passed over in promotion because his ‘right-wing’ colleagues (the term used in Economics those days was ‘neo-classical’—in the same pejorative way the term ‘neo-liberal’ is used nowadays) were biased in undervaluing his work. This after a time did not work, as even some leftist scholars in the Department shared views similar to those of the ‘right-wing’ colleagues on this matter. Then he tried a different tack. For one thing, it is not nearly as newfangled as we usually conceive of it. It does not represent a radical rupture with everything that came before, either in human history or in the vastly longer history of nature that precedes the first appearance of our species. It is, rather, only the most recent permutation of a complex of behaviors that is as deeply rooted in who we are as a species as anything else we do: our storytelling, our fashions, our friendships; our evolution as beings that inhabit a universe dense with symbols.

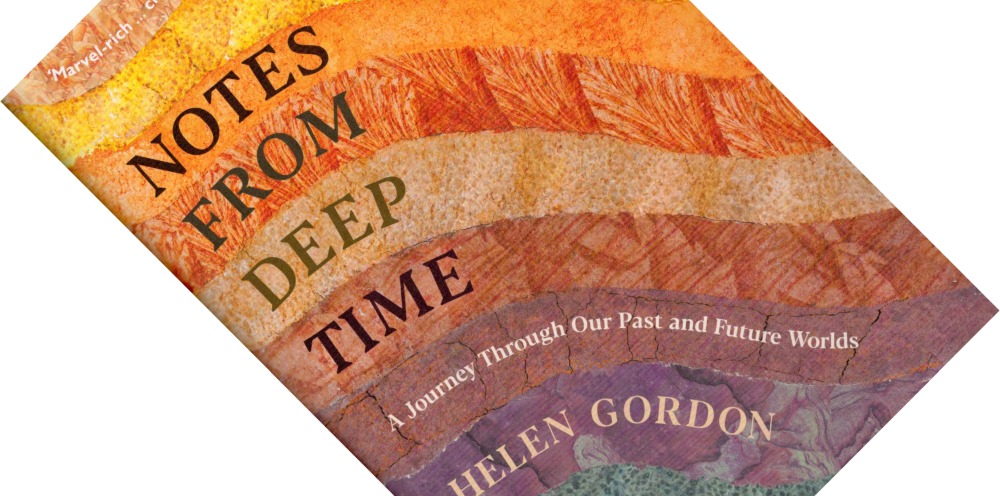

For one thing, it is not nearly as newfangled as we usually conceive of it. It does not represent a radical rupture with everything that came before, either in human history or in the vastly longer history of nature that precedes the first appearance of our species. It is, rather, only the most recent permutation of a complex of behaviors that is as deeply rooted in who we are as a species as anything else we do: our storytelling, our fashions, our friendships; our evolution as beings that inhabit a universe dense with symbols. Deep time is, to me, one of the most awe-inspiring concepts to come out of the earth sciences. Getting to grips with the incomprehensibly vast stretches of time over which geological processes play out is not easy. We are,

Deep time is, to me, one of the most awe-inspiring concepts to come out of the earth sciences. Getting to grips with the incomprehensibly vast stretches of time over which geological processes play out is not easy. We are,  On his daily podcast, the conservative commentator and #NeverTrumper Charlie Sykes often refers to Donald Trump as “the orange god-king” and to the former president’s fervent MAGA following as a “cult.” The jibe may be intended for laughs, but it hints at a deeper truth: The neoauthoritarian leaders of the present era have more than a little in common with the divine kings of the ancient world, and the enchanted worldviews of those who follow Donald Trump and others like him often verge on premodern magical thinking. In this respect, Trump and Trumpism are but one example of a global phenomenon, with similar figures and their similarly devout followers everywhere from Russia, Hungary, and Turkey to Brazil, the Philippines, and—possibly, with its own special characteristics—the new-old Middle Kingdom of the People’s Republic of China.

On his daily podcast, the conservative commentator and #NeverTrumper Charlie Sykes often refers to Donald Trump as “the orange god-king” and to the former president’s fervent MAGA following as a “cult.” The jibe may be intended for laughs, but it hints at a deeper truth: The neoauthoritarian leaders of the present era have more than a little in common with the divine kings of the ancient world, and the enchanted worldviews of those who follow Donald Trump and others like him often verge on premodern magical thinking. In this respect, Trump and Trumpism are but one example of a global phenomenon, with similar figures and their similarly devout followers everywhere from Russia, Hungary, and Turkey to Brazil, the Philippines, and—possibly, with its own special characteristics—the new-old Middle Kingdom of the People’s Republic of China. History doesn’t repeat itself. It just tries to remember an old song it heard once. It may be that Putin’s 24 February 2022 will turn out to be like Hitler’s 22 June 1941 – the day he invaded Russia, doomed himself and Germany to destruction and made inevitable a divided

History doesn’t repeat itself. It just tries to remember an old song it heard once. It may be that Putin’s 24 February 2022 will turn out to be like Hitler’s 22 June 1941 – the day he invaded Russia, doomed himself and Germany to destruction and made inevitable a divided  IN 1998, Lucy Sante published The Factory of Facts, a memoir of her childhood in Belgium and the Sante family’s stuttering moves back and forth (and finally forth) to the States—ultimately, to Summit, New Jersey—when she was eight, in 1962. Toward the end of the memoir, she marks her story as a displacement, “as if I were writing about someone else.” Sante is talking, here, about the French of her youth contrasted with the English of America, and how “languages are not equivalent one to another.” Something else is in play, though. The eight-year-old boy that Sante speaks for would need to translate her English words, written much later in America, “and that would mean engaging an electrical circuit in his brain, bypassing his heart.”

IN 1998, Lucy Sante published The Factory of Facts, a memoir of her childhood in Belgium and the Sante family’s stuttering moves back and forth (and finally forth) to the States—ultimately, to Summit, New Jersey—when she was eight, in 1962. Toward the end of the memoir, she marks her story as a displacement, “as if I were writing about someone else.” Sante is talking, here, about the French of her youth contrasted with the English of America, and how “languages are not equivalent one to another.” Something else is in play, though. The eight-year-old boy that Sante speaks for would need to translate her English words, written much later in America, “and that would mean engaging an electrical circuit in his brain, bypassing his heart.” I

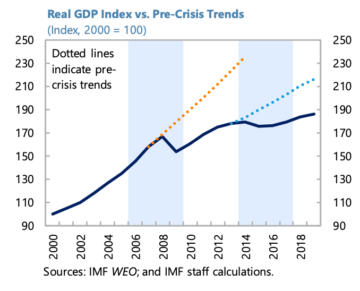

I  Adam Tooze over at his substack:

Adam Tooze over at his substack:

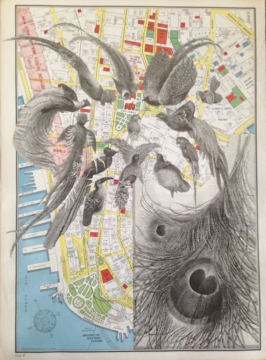

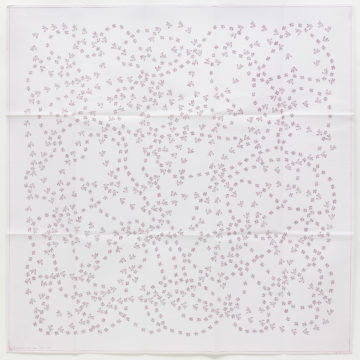

Maya Adereth and Neil Warner interview Michael Mann in Phenomenal World (image León Ferrari,

Maya Adereth and Neil Warner interview Michael Mann in Phenomenal World (image León Ferrari,  Francis Fukuyama in the Financial Times (photo by Harry Mitchell):

Francis Fukuyama in the Financial Times (photo by Harry Mitchell): The actor, writer and consummate New Yawker Harvey Fierstein is assuredly a man of many talents. Who knew needlework was one of them?

The actor, writer and consummate New Yawker Harvey Fierstein is assuredly a man of many talents. Who knew needlework was one of them? FEATURING HIS SELF MADE SAILOR’S HAT until his last days, Lawrence Weiner never tired of reminding us that WE ARE SHIPS AT SEA NOT DUCKS ON A POND, apparently sharing Otto Neurath’s moral imperative. The necessity of citing Weiner verbatim in the very first sentence (and in nearly every paragraph) of this homage already signals the extent to which his work contested—if not disqualified—the legitimacy of critical and historical ekphrasis. Every single one of his statements aimed at dismantling linguistic conventions (of plasticity, of poetry, of metaphor, of metaphysical thinking) and disputed the conciliatory potential of cultural practices. In a 1969 interview, Leo Castelli, an early admirer of Weiner who became his dealer after the artist parted ways with Seth Siegelaub, presciently identified the work—both literally and figuratively—as “the writing on the wall,” rightfully sensing the terminal radicality of its innate anti-aesthetic.

FEATURING HIS SELF MADE SAILOR’S HAT until his last days, Lawrence Weiner never tired of reminding us that WE ARE SHIPS AT SEA NOT DUCKS ON A POND, apparently sharing Otto Neurath’s moral imperative. The necessity of citing Weiner verbatim in the very first sentence (and in nearly every paragraph) of this homage already signals the extent to which his work contested—if not disqualified—the legitimacy of critical and historical ekphrasis. Every single one of his statements aimed at dismantling linguistic conventions (of plasticity, of poetry, of metaphor, of metaphysical thinking) and disputed the conciliatory potential of cultural practices. In a 1969 interview, Leo Castelli, an early admirer of Weiner who became his dealer after the artist parted ways with Seth Siegelaub, presciently identified the work—both literally and figuratively—as “the writing on the wall,” rightfully sensing the terminal radicality of its innate anti-aesthetic. Bones: They hold us upright, protect our innards, allow us to move our limbs and generally keep us from collapsing into a fleshy puddle on the floor. When we’re young, they grow with us and easily heal from playground fractures. When we’re old, they tend to weaken, and may break after a fall or even require mechanical replacement. If that structural role was all that bones did for us, it would be plenty.

Bones: They hold us upright, protect our innards, allow us to move our limbs and generally keep us from collapsing into a fleshy puddle on the floor. When we’re young, they grow with us and easily heal from playground fractures. When we’re old, they tend to weaken, and may break after a fall or even require mechanical replacement. If that structural role was all that bones did for us, it would be plenty. It’s a rare Washington memoir that makes you gasp in the very second sentence. Here’s the first sentence from

It’s a rare Washington memoir that makes you gasp in the very second sentence. Here’s the first sentence from