Shahidha Bari in The Guardian:

How do you evade a rampaging crocodile? By zigzagging as you run, according to Margaret Atwood, since crocodiles, apparently, struggle to navigate corners. It’s a piece of wisdom she imparts in passing in one of the essays in her latest collection. To be clear, the burning questions of the title are less to do with crocodiles and more concerned with those issues “we’ve been faced with for a century and more: urgent climate change, wealth inequality and democracy in peril”. The most serious questions of all, then. Still, the crocodiles are indicative of a sensibility that prevails throughout: droll, deadpan humour and an instinct for self-deprecation that saves the work from grandstanding or piety.

How do you evade a rampaging crocodile? By zigzagging as you run, according to Margaret Atwood, since crocodiles, apparently, struggle to navigate corners. It’s a piece of wisdom she imparts in passing in one of the essays in her latest collection. To be clear, the burning questions of the title are less to do with crocodiles and more concerned with those issues “we’ve been faced with for a century and more: urgent climate change, wealth inequality and democracy in peril”. The most serious questions of all, then. Still, the crocodiles are indicative of a sensibility that prevails throughout: droll, deadpan humour and an instinct for self-deprecation that saves the work from grandstanding or piety.

The novelist’s essay collection has become a curious genre in recent years. Zadie Smith and Salman Rushdie periodically produce them to fanfare, but really there’s no reason for us to expect writers of fiction to be qualified to comment on fact. For every writer that proves themself a stylish and smart observer of reality, another dismays us with windbaggery and vanity. Atwood’s essays luckily escape that, but they do have the whiff of a publisher capitalising on the odds and ends that litter the successful writer’s desk – the keynote speech here, the guest lecture there. Still, there’s something cheerfully game about how politely Atwood thanks her hosts for their invitations to speak at the “Carleton School of Journalism and Communication”, “the Charles Sauriol Environmental Dinner” and the “Department of Forestry’s Centennial”. She’s both gracious and tongue-in‑cheek about the grandeur of these occasions.

More here.

Nearly 200 countries have agreed to start negotiations on an international agreement to take action on the “plastic crisis”. UN members are tasked with developing an over-arching framework for reducing plastic waste across the world. There is growing concern that discarded plastic is destroying habitats, harming wildlife and contaminating the food chain. Supporters describe the move as one of the world’s most ambitious environmental actions since the 1989 Montreal Protocol, which phased out ozone-depleting substances.

Nearly 200 countries have agreed to start negotiations on an international agreement to take action on the “plastic crisis”. UN members are tasked with developing an over-arching framework for reducing plastic waste across the world. There is growing concern that discarded plastic is destroying habitats, harming wildlife and contaminating the food chain. Supporters describe the move as one of the world’s most ambitious environmental actions since the 1989 Montreal Protocol, which phased out ozone-depleting substances. Some philosophical ideas have a bad reputation: until a few centuries ago, for example, in Christian Europe it was quite dangerous to profess atheism. Present-day forbidden ideas put you at risk of a shit-storm rather than the stake, but it’s still interesting to explore the philosophical taboos of our era.

Some philosophical ideas have a bad reputation: until a few centuries ago, for example, in Christian Europe it was quite dangerous to profess atheism. Present-day forbidden ideas put you at risk of a shit-storm rather than the stake, but it’s still interesting to explore the philosophical taboos of our era. Scientists have released three studies that reveal intriguing new clues about how the COVID-19 pandemic started. Two of the reports trace the outbreak back to a massive market that sold live animals, among other goods, in Wuhan, China

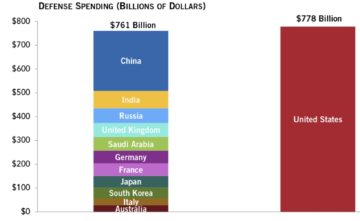

Scientists have released three studies that reveal intriguing new clues about how the COVID-19 pandemic started. Two of the reports trace the outbreak back to a massive market that sold live animals, among other goods, in Wuhan, China The state of U.S. defense spending is often boiled down to eye-catching but incomplete statistics. On one side, the U.S. spends more than the next

The state of U.S. defense spending is often boiled down to eye-catching but incomplete statistics. On one side, the U.S. spends more than the next  In our quest to find what makes humans unique, we often compare ourselves with our closest relatives: the great apes. But when it comes to understanding the quintessentially human capacity for language, scientists are finding that the most tantalizing clues lay farther afield.

In our quest to find what makes humans unique, we often compare ourselves with our closest relatives: the great apes. But when it comes to understanding the quintessentially human capacity for language, scientists are finding that the most tantalizing clues lay farther afield. “Cocaine is an alkaloid found in the leaves of the coca plant, Erythroxylum coca, which is native to South America. For centuries, the leaves have been chewed by South American people as a mild stimulant and appetite suppressant. Coca was brought back to Europe by the Spanish in the 16th century. Cocaine itself was first isolated by Friedrich Gaedcke in 1855, and an improved purification process was developed by Albert Niemann in 1860. Later, it came to be incorporated into tonic drinks, such as Coca-Cola in 1866, and was available over the counter at Harrods in London until as late as 1916.

“Cocaine is an alkaloid found in the leaves of the coca plant, Erythroxylum coca, which is native to South America. For centuries, the leaves have been chewed by South American people as a mild stimulant and appetite suppressant. Coca was brought back to Europe by the Spanish in the 16th century. Cocaine itself was first isolated by Friedrich Gaedcke in 1855, and an improved purification process was developed by Albert Niemann in 1860. Later, it came to be incorporated into tonic drinks, such as Coca-Cola in 1866, and was available over the counter at Harrods in London until as late as 1916. In 1999, Nina Khrushcheva met William F. Buckley at the offices of National Review. Then a fellow at the New School’s World Policy Institute (and now a professor of international affairs at the university) Khrushcheva had much to discuss with Buckley, whom she’d first met a few months earlier at an event commemorating the tenth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. Buckley had been a panelist along with her uncle Sergey, son of the Cold War-era Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev, one of Buckley’s sworn enemies in his, and the conservative movement’s, ferocious fight against Communism.

In 1999, Nina Khrushcheva met William F. Buckley at the offices of National Review. Then a fellow at the New School’s World Policy Institute (and now a professor of international affairs at the university) Khrushcheva had much to discuss with Buckley, whom she’d first met a few months earlier at an event commemorating the tenth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. Buckley had been a panelist along with her uncle Sergey, son of the Cold War-era Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev, one of Buckley’s sworn enemies in his, and the conservative movement’s, ferocious fight against Communism. An Oxford undergraduate once wrote a brilliant answer to an exam question about the logic of natural selection, ending with the statement: “And here I rely heavily on the words of Richard Dawkins.” When the exam marker, one Marian Stamp Dawkins, noticed this, she wrote in the margin of the paper: “Yes. Don’t we all?”

An Oxford undergraduate once wrote a brilliant answer to an exam question about the logic of natural selection, ending with the statement: “And here I rely heavily on the words of Richard Dawkins.” When the exam marker, one Marian Stamp Dawkins, noticed this, she wrote in the margin of the paper: “Yes. Don’t we all?” So much is being written about the Russian invasion of Ukraine that more on the situation on the ground is unnecessary. Certainly, it is premature for a post-mortem on causes and responsibilities of a conflict that came on so quickly and unexpectedly. But it is not a bad time to think about medium- and long-term consequences of Putin’s dramatic action, and how the West can recover its equilibrium and face up to a new global challenge.

So much is being written about the Russian invasion of Ukraine that more on the situation on the ground is unnecessary. Certainly, it is premature for a post-mortem on causes and responsibilities of a conflict that came on so quickly and unexpectedly. But it is not a bad time to think about medium- and long-term consequences of Putin’s dramatic action, and how the West can recover its equilibrium and face up to a new global challenge. A

A  It’s not just their ability to run 42 kilometres that separates marathon runners from the rest of us. They’ve got a secret energy source hidden deep inside: a special bacteria in their gut turns a painful waste material into energy. No doping scandal required!

It’s not just their ability to run 42 kilometres that separates marathon runners from the rest of us. They’ve got a secret energy source hidden deep inside: a special bacteria in their gut turns a painful waste material into energy. No doping scandal required! “Perhaps there would be a birth of a whole new era of the sciences and arts,” German romantic thinker Friedrich Schlegel hoped, “if symphilosophy and sympoetry became so universal and heartful that it would no longer be extraordinary for several complementary minds to create communal works of art. One is often struck by the idea that two minds really belong together … to realize their full potential only when joined … an art of amalgamating individuals.”

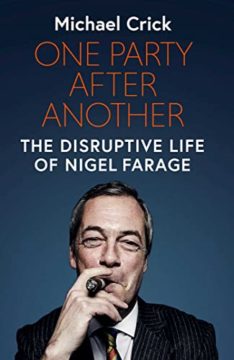

“Perhaps there would be a birth of a whole new era of the sciences and arts,” German romantic thinker Friedrich Schlegel hoped, “if symphilosophy and sympoetry became so universal and heartful that it would no longer be extraordinary for several complementary minds to create communal works of art. One is often struck by the idea that two minds really belong together … to realize their full potential only when joined … an art of amalgamating individuals.” The consequences of Farage’s ubiquity have been seismic, reshaping the UK and the wider political landscape. He sought a referendum on Britain’s membership of the EU and then a hard Brexit, and ultimately got everything he wanted. The Conservative Party’s embrace of a form of English nationalism was partly a response to the threat that Farage posed. The near-silence of the Labour leader, Keir Starmer, on the subject of Brexit is a form of vindication for him. Starmer knows that Brexit is having calamitous consequences but does not dare to say so. No wonder Michael Crick concludes that ‘it’s hard to think of any other politician in the last 150 years who has had so much impact on British history without being a senior member of one of the major parties at the time’.

The consequences of Farage’s ubiquity have been seismic, reshaping the UK and the wider political landscape. He sought a referendum on Britain’s membership of the EU and then a hard Brexit, and ultimately got everything he wanted. The Conservative Party’s embrace of a form of English nationalism was partly a response to the threat that Farage posed. The near-silence of the Labour leader, Keir Starmer, on the subject of Brexit is a form of vindication for him. Starmer knows that Brexit is having calamitous consequences but does not dare to say so. No wonder Michael Crick concludes that ‘it’s hard to think of any other politician in the last 150 years who has had so much impact on British history without being a senior member of one of the major parties at the time’.