Maggie Doherty at The Nation:

“Does Anyone Have the Right to Sex?” was a shrewd yet compassionate essay, marked by rigorous thinking as well as the hope that we might make room for desires that don’t follow patriarchy’s scripts, without blaming people for desiring what they’ve been told to want. Srinivasan gestured in the essay toward a new feminist perspective, one that would draw on the work of the second-wave feminists of the 1960s and ’70s, who took questions of sexual desire seriously, without replicating some of their blind spots concerning race and class. Such a perspective would also preserve aspects of more recent feminist thinking—an emphasis on individual freedom, an awareness of the ways different forms of oppression intersect—without suggesting that desire is inherently good or just. Her aim was not to legislate anyone’s desires—that would be authoritarian—but rather to encourage readers to question their sexual preferences, to see their own desires as a starting point for inquiry rather than its end. There is no right to sex, she wrote, but there may be “a duty to transfigure, as best we can, our desires” so that they better align with our political goals

“Does Anyone Have the Right to Sex?” was a shrewd yet compassionate essay, marked by rigorous thinking as well as the hope that we might make room for desires that don’t follow patriarchy’s scripts, without blaming people for desiring what they’ve been told to want. Srinivasan gestured in the essay toward a new feminist perspective, one that would draw on the work of the second-wave feminists of the 1960s and ’70s, who took questions of sexual desire seriously, without replicating some of their blind spots concerning race and class. Such a perspective would also preserve aspects of more recent feminist thinking—an emphasis on individual freedom, an awareness of the ways different forms of oppression intersect—without suggesting that desire is inherently good or just. Her aim was not to legislate anyone’s desires—that would be authoritarian—but rather to encourage readers to question their sexual preferences, to see their own desires as a starting point for inquiry rather than its end. There is no right to sex, she wrote, but there may be “a duty to transfigure, as best we can, our desires” so that they better align with our political goals

more here.

Understanding this complex tangle of overlapping titles and jurisdictions is here essential. For although Maria Theresa was sovereign in her own right of the archduchy of Austria and queen of Hungary, in legal theory she ranked lower than her husband, the newly elected emperor. Yet having regained her realms as a woman against one set of male rivals, Maria Theresa was determined not to cede authority to another set closer to home. She insisted that her power within her inherited possessions was absolute. Stollberg-Rilinger argues that even within the Holy Roman Empire, nominally her husband’s domain, it was Maria Theresa, not the emperor, who decided the direction of policy. This female primacy would be continued, with even sharper resentment on the part of the subordinated male, after Francis’s death in 1765 and the election of her eldest son, Joseph II, as his successor as Holy Roman Emperor.

Understanding this complex tangle of overlapping titles and jurisdictions is here essential. For although Maria Theresa was sovereign in her own right of the archduchy of Austria and queen of Hungary, in legal theory she ranked lower than her husband, the newly elected emperor. Yet having regained her realms as a woman against one set of male rivals, Maria Theresa was determined not to cede authority to another set closer to home. She insisted that her power within her inherited possessions was absolute. Stollberg-Rilinger argues that even within the Holy Roman Empire, nominally her husband’s domain, it was Maria Theresa, not the emperor, who decided the direction of policy. This female primacy would be continued, with even sharper resentment on the part of the subordinated male, after Francis’s death in 1765 and the election of her eldest son, Joseph II, as his successor as Holy Roman Emperor. THE HARVARD

THE HARVARD When guests used to visit Vladimir Putin in his office in the Kremlin’s Senate Palace, he’d point at the bookshelves and ask them to choose a book from Joseph Stalin’s library. Half of Stalin’s books – usually marked up by the Soviet leader himself with red or green crayons – remain in Putin’s office. As one of his ministers told me, Putin would ask the visitor to open the book and they would look together at whatever marginalia Stalin had written: sometimes it was a grim laugh: “xa-xa-xa!”; sometimes a snort of disdain: “green steam!”; at others it was just a word: “teacher” was written on the biography of Ivan the Terrible.

When guests used to visit Vladimir Putin in his office in the Kremlin’s Senate Palace, he’d point at the bookshelves and ask them to choose a book from Joseph Stalin’s library. Half of Stalin’s books – usually marked up by the Soviet leader himself with red or green crayons – remain in Putin’s office. As one of his ministers told me, Putin would ask the visitor to open the book and they would look together at whatever marginalia Stalin had written: sometimes it was a grim laugh: “xa-xa-xa!”; sometimes a snort of disdain: “green steam!”; at others it was just a word: “teacher” was written on the biography of Ivan the Terrible. Are there unrappable words? Not words that can’t be gerrymandered into rhyme by tricks of truncation or pronunciation, but words so ungainly, so unwieldy, so unhip, so unhip-hop, as to definitively resist rap’s tractor-beam powers of assimilation. Do such words exist? No! says the wide-eyed idealist in me. I mean, probably, says the grizzled skeptic, who doubts I’ll hear pulchritude or amortize or hoarfrost or chilblains dropped over a beat before I die.

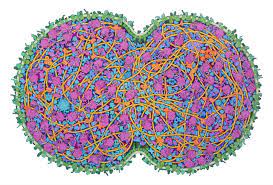

Are there unrappable words? Not words that can’t be gerrymandered into rhyme by tricks of truncation or pronunciation, but words so ungainly, so unwieldy, so unhip, so unhip-hop, as to definitively resist rap’s tractor-beam powers of assimilation. Do such words exist? No! says the wide-eyed idealist in me. I mean, probably, says the grizzled skeptic, who doubts I’ll hear pulchritude or amortize or hoarfrost or chilblains dropped over a beat before I die. Intelligent decision-making doesn’t require a brain. You were capable of it before you even had one. Beginning life as a single fertilised egg, you divided and became a mass of genetically identical cells. They chattered among themselves to fashion a complex anatomical structure – your body. Even more remarkably, if you had split in two as an embryo, each half would have been able to replace what was missing, leaving you as one of two identical (monozygotic) twins. Likewise, if two mouse embryos are mushed together like a snowball, a single, normal mouse results. Just how do these embryos know what to do? We have no technology yet that has this degree of plasticity – recognising a deviation from the normal course of events and responding to achieve the same outcome overall.

Intelligent decision-making doesn’t require a brain. You were capable of it before you even had one. Beginning life as a single fertilised egg, you divided and became a mass of genetically identical cells. They chattered among themselves to fashion a complex anatomical structure – your body. Even more remarkably, if you had split in two as an embryo, each half would have been able to replace what was missing, leaving you as one of two identical (monozygotic) twins. Likewise, if two mouse embryos are mushed together like a snowball, a single, normal mouse results. Just how do these embryos know what to do? We have no technology yet that has this degree of plasticity – recognising a deviation from the normal course of events and responding to achieve the same outcome overall. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine took much of the world by surprise. It is an unprovoked and unjustified attack that will go down in history as one of the major war crimes of the 21st century, argues Noam Chomsky in the exclusive interview for Truthout that follows. Political considerations, such as those cited by Russian President Vladimir Putin, cannot be used as arguments to justify the launching of an invasion against a sovereign nation. In the face of this horrific invasion, though, the U.S. must choose urgent diplomacy over military escalation, as the latter could constitute a “death warrant for the species, with no victors,” Chomsky says.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine took much of the world by surprise. It is an unprovoked and unjustified attack that will go down in history as one of the major war crimes of the 21st century, argues Noam Chomsky in the exclusive interview for Truthout that follows. Political considerations, such as those cited by Russian President Vladimir Putin, cannot be used as arguments to justify the launching of an invasion against a sovereign nation. In the face of this horrific invasion, though, the U.S. must choose urgent diplomacy over military escalation, as the latter could constitute a “death warrant for the species, with no victors,” Chomsky says. P

P It was by accident that Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, a Dutch cloth merchant, first saw a living cell. He’d begun making magnifying lenses at home, perhaps to better judge the quality of his cloth. One day, out of curiosity, he held one up to a drop of lake water. He saw that the drop was teeming with numberless tiny animals. These animalcules, as he called them, were everywhere he looked—in the stuff between his teeth, in soil, in food gone bad. A decade earlier, in 1665, an Englishman named Robert Hooke had examined cork through a lens; he’d found structures that he called “cells,” and the name had stuck. Van Leeuwenhoek seemed to see an even more striking view: his cells moved with apparent purpose. No one believed him when he told people what he’d discovered, and he had to ask local bigwigs—the town priest, a notary, a lawyer—to peer through his lenses and attest to what they saw.

It was by accident that Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, a Dutch cloth merchant, first saw a living cell. He’d begun making magnifying lenses at home, perhaps to better judge the quality of his cloth. One day, out of curiosity, he held one up to a drop of lake water. He saw that the drop was teeming with numberless tiny animals. These animalcules, as he called them, were everywhere he looked—in the stuff between his teeth, in soil, in food gone bad. A decade earlier, in 1665, an Englishman named Robert Hooke had examined cork through a lens; he’d found structures that he called “cells,” and the name had stuck. Van Leeuwenhoek seemed to see an even more striking view: his cells moved with apparent purpose. No one believed him when he told people what he’d discovered, and he had to ask local bigwigs—the town priest, a notary, a lawyer—to peer through his lenses and attest to what they saw. No clear genetic origin has been found for stuttering, and neither have emotional origins like trauma been ruled out. Still there is no cure. Some techniques work for some stutterers, some of the time. A hundred years ago doctors tried cutting out portions of the tongues of stutterers, killing and maiming many, curing none. Online, there are testimonies from people who swear by certain techniques, people who are taking Vitamin B1, people who are gloriously fluent, and people in the midst of a tough recurrence.

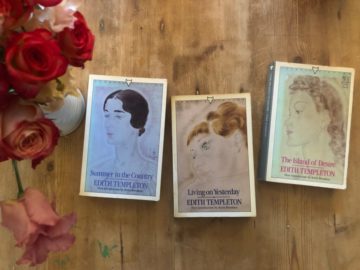

No clear genetic origin has been found for stuttering, and neither have emotional origins like trauma been ruled out. Still there is no cure. Some techniques work for some stutterers, some of the time. A hundred years ago doctors tried cutting out portions of the tongues of stutterers, killing and maiming many, curing none. Online, there are testimonies from people who swear by certain techniques, people who are taking Vitamin B1, people who are gloriously fluent, and people in the midst of a tough recurrence. Such sexually explicit content became what Templeton was best known for during her lifetime—a reputation made yet more notorious due to the fact that she drew direct inspiration from her own illicit trysts. She was born into a wealthy upper-class family in Prague in 1916, and raised in a world of sophistication, civility, and gentility: this social milieu would have been shocked by such self-exposing erotica. Edith Passerová, as she was then, met her first husband, the Englishman William Stockwell Templeton, when she was only seventeen. They married five years later, in 1938, and lived in England. The union quickly disintegrated, but rather than return home to what by that point was a war-torn Europe, Templeton remained in Britain after their separation. She initially took a job with the American War Office, during which time she had the brief fling described in “The Darts of Cupid.” The story’s candid, violently charged eroticism caused a stir when it was first published in The New Yorker, but even its level of graphic sexual detail paled in comparison to that of Templeton’s most famous novel.

Such sexually explicit content became what Templeton was best known for during her lifetime—a reputation made yet more notorious due to the fact that she drew direct inspiration from her own illicit trysts. She was born into a wealthy upper-class family in Prague in 1916, and raised in a world of sophistication, civility, and gentility: this social milieu would have been shocked by such self-exposing erotica. Edith Passerová, as she was then, met her first husband, the Englishman William Stockwell Templeton, when she was only seventeen. They married five years later, in 1938, and lived in England. The union quickly disintegrated, but rather than return home to what by that point was a war-torn Europe, Templeton remained in Britain after their separation. She initially took a job with the American War Office, during which time she had the brief fling described in “The Darts of Cupid.” The story’s candid, violently charged eroticism caused a stir when it was first published in The New Yorker, but even its level of graphic sexual detail paled in comparison to that of Templeton’s most famous novel. A week ago I unrestrainedly used the phrase Слава Україні!/Glory to Ukraine!, and a few friends and readers were surprised to see me resorting to jingoism, even if for a country not my own. This struck some as particularly inadvisable, since the phrase is associated in some of its expressions with far-right Ukrainian nationalism, and with the handful of people in Ukraine who minimally justify Putin’s claim to be undertaking a campaign of “de-Nazification” there. The first time I used the phrase was in 2014, at a rally in Paris in support of the Maidan demonstrators in Kyiv, among a Ukrainian diaspora that was resolutely pro-democracy and worlds away from any far-right sentiments. But a rally is one thing, an essay another, and as the week wore on I admit my use of the phrase echoed in my mind, and came to feel increasingly like a mistake.

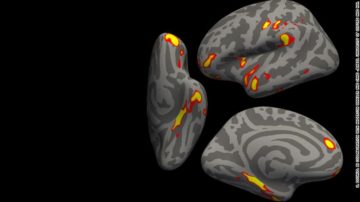

A week ago I unrestrainedly used the phrase Слава Україні!/Glory to Ukraine!, and a few friends and readers were surprised to see me resorting to jingoism, even if for a country not my own. This struck some as particularly inadvisable, since the phrase is associated in some of its expressions with far-right Ukrainian nationalism, and with the handful of people in Ukraine who minimally justify Putin’s claim to be undertaking a campaign of “de-Nazification” there. The first time I used the phrase was in 2014, at a rally in Paris in support of the Maidan demonstrators in Kyiv, among a Ukrainian diaspora that was resolutely pro-democracy and worlds away from any far-right sentiments. But a rally is one thing, an essay another, and as the week wore on I admit my use of the phrase echoed in my mind, and came to feel increasingly like a mistake. People who have even a mild case of Covid-19 may have accelerated aging of the brain and other changes to it, according to a new study.

People who have even a mild case of Covid-19 may have accelerated aging of the brain and other changes to it, according to a new study. Morgan Meis (MM): Jed, your new book, Authority and Freedom*, has come out in the last few weeks. Congratulations! In it, right near the end, you give this lovely quote from WH Auden, from his poem about Yeats:

Morgan Meis (MM): Jed, your new book, Authority and Freedom*, has come out in the last few weeks. Congratulations! In it, right near the end, you give this lovely quote from WH Auden, from his poem about Yeats: Thursday morning, after the publication of

Thursday morning, after the publication of