Oliver Muday in The Atlantic:

One morning a few weeks ago, I sent my friend a Proust text. It was a photo of a page from Swann’s Way, and it took several attempts for me to capture the near-page-length sentence in its entirety. Next to me, my 2-year-old daughter slowly guided a spoonful of oatmeal into her mouth, noticing my struggle. “Daddy, what are you doing?” she asked. The answer: being insufferable. My friend’s response shortly thereafter confirmed this: “It’s too early for me to follow this sentence.”

One morning a few weeks ago, I sent my friend a Proust text. It was a photo of a page from Swann’s Way, and it took several attempts for me to capture the near-page-length sentence in its entirety. Next to me, my 2-year-old daughter slowly guided a spoonful of oatmeal into her mouth, noticing my struggle. “Daddy, what are you doing?” she asked. The answer: being insufferable. My friend’s response shortly thereafter confirmed this: “It’s too early for me to follow this sentence.”

Proust’s work has many qualities that might recommend it for pandemic reading: the author’s concern with the protean nature of time, the transportive exploration of memory and the past, or simply the pleasure of immersing oneself in the richly detailed life of another. His novel cycle, In Search of Lost Time, also presents the attractive challenge of surmounting a massive text—multiple volumes, stretching between 3,000 and 4,000 pages, depending on the edition—and the subsequent entry into a rare and rather pretentious club of readers. All of it appealed; I wanted in. What I found was a novel so preoccupied with the minutiae of experience that I had no choice but to reappraise my own.

Before accepting that I was no different from everyone else sublimating their ambition into a “quar project,” my reading habits had changed naturally with the phases of the pandemic. Early in March, as New York City prepared for a shutdown, I felt a sense of adventure in ordering a stockpile of books along with black beans and toilet paper. My first batch included Thomas Bernhard’s Extinction and Penelope Fitzgerald’s The Beginning of Spring, works often cited for their distinctive styles of comedy (self-lacerating and wry, respectively). One night, the two novels happened to be stacked on top of each other beside my bed; I found myself haunted by the cryptic dispatch of their titles.

More here.

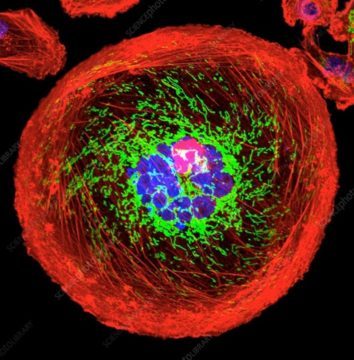

Ninety percent cancers diagnosed at Stage I are cured. Ninety percent diagnosed at Stage IV are not. Early detection saves lives. Unfortunately, more than a third of the patients already have advanced disease at diagnosis. Most die. We can, and must, do better. But why be satisfied with diagnosing Stage I disease that also requires disfiguring and invasive treatments? Why not aim higher and track down the origin of cancer? The First Cell. To do so, cancer must be caught at birth. This remains a challenging problem for researchers.

Ninety percent cancers diagnosed at Stage I are cured. Ninety percent diagnosed at Stage IV are not. Early detection saves lives. Unfortunately, more than a third of the patients already have advanced disease at diagnosis. Most die. We can, and must, do better. But why be satisfied with diagnosing Stage I disease that also requires disfiguring and invasive treatments? Why not aim higher and track down the origin of cancer? The First Cell. To do so, cancer must be caught at birth. This remains a challenging problem for researchers. In the beginning, the god of the

In the beginning, the god of the  In long plane journeys I do not sleep well. But some years back in one such journey I was tired and fell fast asleep. When I woke up, I saw a little note on my lap. It was from the captain in charge of the plane. It said, “I did not want to disturb you, but from our computer log I could see that your total travel so far with our airlines group just crossed 3 million miles. So congratulations! It seems you travel almost as much as I do.” I made a quick calculation, 3 million miles is like 6 return trips from the earth to the moon. With a deep sigh I chanted to myself, as our plane was hurtling through the night sky, a word from an ancient Sanskrit hymn: Charaiveti (keep moving!)

In long plane journeys I do not sleep well. But some years back in one such journey I was tired and fell fast asleep. When I woke up, I saw a little note on my lap. It was from the captain in charge of the plane. It said, “I did not want to disturb you, but from our computer log I could see that your total travel so far with our airlines group just crossed 3 million miles. So congratulations! It seems you travel almost as much as I do.” I made a quick calculation, 3 million miles is like 6 return trips from the earth to the moon. With a deep sigh I chanted to myself, as our plane was hurtling through the night sky, a word from an ancient Sanskrit hymn: Charaiveti (keep moving!)

Blood of the Beasts (Le sang des bêtes)

Blood of the Beasts (Le sang des bêtes)

One of my oldest friends, an economic historian who serves as the Academic Director of a museum of Jewish life in northern Germany, is, like me, a child of May; and, during our recent birthday month, as is our custom, we exchanged gifts by post. Since we also share a love of books and history and a taste for grand, occasionally outlandish theory, as well as an abhorrence for futuristic science fiction, the novels we sent each other were in equal measures fantastical and backward-looking: examples of counterfactual historical fiction, what has come to be known as uchronia, the imaginative remaking of a bygone era that is the temporal counterpart to utopian geography.

One of my oldest friends, an economic historian who serves as the Academic Director of a museum of Jewish life in northern Germany, is, like me, a child of May; and, during our recent birthday month, as is our custom, we exchanged gifts by post. Since we also share a love of books and history and a taste for grand, occasionally outlandish theory, as well as an abhorrence for futuristic science fiction, the novels we sent each other were in equal measures fantastical and backward-looking: examples of counterfactual historical fiction, what has come to be known as uchronia, the imaginative remaking of a bygone era that is the temporal counterpart to utopian geography.

It wasn’t effortless but we managed to mollify, sidestep and defy enough authorities to be legally resident in Finland for the month of July. Never mind shoes and belts off and toothpaste in a plastic bag. No, do mind; do that too. But add PCR test results, Covid vaccination cards and popup, improvised airport queues. And a novel Coronavirus variant: marriage certificates on demand.

It wasn’t effortless but we managed to mollify, sidestep and defy enough authorities to be legally resident in Finland for the month of July. Never mind shoes and belts off and toothpaste in a plastic bag. No, do mind; do that too. But add PCR test results, Covid vaccination cards and popup, improvised airport queues. And a novel Coronavirus variant: marriage certificates on demand.  Once upon a time, I decided to start answering the question “Where are you from?” with “The middle of the Pacific Ocean.” I never followed through, though I still think it’s a good answer. I have spent so much of my life bouncing back and forth between the United States and India that, for me, the concept of home is more like a stationary probability distribution — a phrase that I filched from a statistics paper once, and which is likely to make less sense to most people than “the middle of the Pacific Ocean.” After all, the latter at least counts as a place.

Once upon a time, I decided to start answering the question “Where are you from?” with “The middle of the Pacific Ocean.” I never followed through, though I still think it’s a good answer. I have spent so much of my life bouncing back and forth between the United States and India that, for me, the concept of home is more like a stationary probability distribution — a phrase that I filched from a statistics paper once, and which is likely to make less sense to most people than “the middle of the Pacific Ocean.” After all, the latter at least counts as a place. The summer wasn’t meant to be like this. By April, Greene County, in southwestern Missouri, seemed to be past

The summer wasn’t meant to be like this. By April, Greene County, in southwestern Missouri, seemed to be past  In October 2018,

In October 2018,