The Novotel Hotel at the Franz Josef Strauss International Airport in Munich, where I stayed overnight in late June.

Month: July 2021

A UAE Style Guest-Worker Programme Is The Least We Should Do To Help The World’s Poor

by Thomas Wells

Billions of people around the world continue to live in great poverty. What is the responsibility of rich countries to address this?

Billions of people around the world continue to live in great poverty. What is the responsibility of rich countries to address this?

This essay takes the view that the best we can do is the least we ought to do, but also that the best we can do is heavily constrained by political feasibility as well as logistics. In a democracy the best we can do is what the majority are willing to go along with, and this is something quite different from what purely moral arguments would suggest. For example, rich countries could increase aid programmes from their current pitiful level of $160 billion (less than 0.2% of global GDP). However this would be unpopular since that money could have been spent on more nice things for their own citizens, and lots of rich country governments are already worrying about how to raise the taxes to pay off their Covid debts. Hence that idea fails the political feasibility test. For another example, rich countries could reduce their trade barriers so that poorer countries can access more economic opportunities. Since trade benefits all parties (by definition) this would be a net benefit to rich countries and so it should be politically feasible even though industries threatened with competition would complain. However, rich countries already have very low or zero tariffs on almost everything that is easy to send around the world, so the impact of further liberalisation would be rather tiny.

But there is something else quite obvious that rich countries could do which would have a dramatic impact on global poverty while also having the political advantage of making rich countries even richer. Globalisation has achieved the (more or less) free movement of goods and capital between countries and this has made the world much richer. But people are mostly still stuck behind political borders. Why shouldn’t labour also be allowed to move to wherever it can earn the best price, i.e. to wherever it can be most productive? This would allow rich countries to get cheap low-skilled labour (e.g. to pick our asparagus and care for our old people) while poor people would get access to higher productivity working environments (and hence higher pay) than they could find in their home countries. According to a 2005 calculation by the World Bank, if rich countries globally used migrants to expand their labour force by just 3% this would generate $300 billion in gains for the migrants’ countries (via remittances) and would also save the rich countries more than $50 billion. In other words, rich countries would get even richer while doing far more good for the world than anything else they could try! Read more »

A Mixed Metaphor

by Jackson Arn

The best thing about a painting is that no two people ever paint the same one. They could be sitting in the same garden, staring at the same tree in the same light, poking the same brush in the same pigments, but in the end none of that matters. The two hypothetical tree-paintings are going to turn out different, because the two hypothetical painters are different also.

The best thing about a painting is that no two people ever paint the same one. They could be sitting in the same garden, staring at the same tree in the same light, poking the same brush in the same pigments, but in the end none of that matters. The two hypothetical tree-paintings are going to turn out different, because the two hypothetical painters are different also.

Because the paintings are different, it stands to reason that one is likely to look better than the other. Not certain, but likely. Granted, if the two painters are five-year-olds lacking fine motor control and knowledge of linear perspective, their trees are bound to be equally bad. And granted, if the two are Leonardo and Picasso, their trees will be equally good—different in style, of course, but alike in goodness. Art is subjective, but like everything else subjectivity has its limits. Most of the time, one person is better at painting.

The person who paints the better tree is not necessarily the more careful painter. One person could sit in the garden all afternoon working on a leaf, wait 20 hours for the planet to roll back around, work on leaf the second, and so on for months until the painting is complete—and completely awful. The other person could show up hungover and underslept, sit for fifteen minutes, stand, and leave behind a better work of art. It’s probably worse the other way around. One person could show up at the crack of dawn, paint with brisk, efficient brushstrokes, and be off in time to fix their kids breakfast, such is their dedication to the twin deities of Art and Family. The second person could arrive weeks later, work for months while their children starve, and paint the better painting, and the only thing the world would care about is that the painting is better. All the advantages person two had, all the time person one was forced to sacrifice—nobody cares. All they care about is who painted the better tree.

Yes, I’m right—it’s much worse that way. And not just because of the starving children.

*

I am not a painter, but I probably could have been. Until very recently, I was a solar engineer. Science always came easy. I never loved it, never got so much as a squirt of dopamine from biology homework or an A plus on a physics exam. It’s just that I was incapable of not getting A pluses in science classes. That was my curse. My unrequested gift.

I can’t remember much about the things I painted back then, but I remember the joy they brought me. Nothing, not even the events of last year, can take that away. All careers in the arts begin with joy. It’s the acorn from which the oak of greatness grows. Inspiration is also needed, and perspiration, and dedication, and luck. But joy is the acorn. Read more »

The justification of Idling

by Emrys Westacott

The work ethic is deeply ingrained in much of modern society, both Eastern and Western, and there are many forces making sure that this remains the case. Parents, teachers, coaches, politicians, employers, and many other shapers of souls or makers of opinion constantly repeat the idea that hard work is the key to success–in any particular endeavour, or in life itself. It would be a brave graduation speaker who seriously urged their young listeners to embrace idleness. (I did once hear Ariana Huffington advise Smith College graduates to “sleep their way to the top,” but she essentially meant that they should avoid burn out by ensuring that they get sufficient rest.)

The work ethic is deeply ingrained in much of modern society, both Eastern and Western, and there are many forces making sure that this remains the case. Parents, teachers, coaches, politicians, employers, and many other shapers of souls or makers of opinion constantly repeat the idea that hard work is the key to success–in any particular endeavour, or in life itself. It would be a brave graduation speaker who seriously urged their young listeners to embrace idleness. (I did once hear Ariana Huffington advise Smith College graduates to “sleep their way to the top,” but she essentially meant that they should avoid burn out by ensuring that they get sufficient rest.)

There are, to be sure, some distinguished critics of the work ethic. In a 1932 essay, “In Praise of Idleness,” Bertrand Russell wrote that “immense harm is caused by the belief that work is virtuous.” In his view, “the morality of work is the morality of slaves, and the modern world has no need of slavery.”

But Russell doesn’t really praise idleness as that word is normally understood. True, what he advocates is less work and more free time so that people can spend most of their days doing as they please. But he clearly thinks that some ways of spending one’s time are better than others. He hopes, for instance, that, better education will reduce the chances that a person’s leisure time will be “spent in pure frivolity.” He prefers active recreation, like dancing, to passive recreation, like watching sport. And he strongly prefers cerebral to manual activity. He writes, for instance, that

moving matter about, while a certain amount of it is necessary, is emphatically not one of the ends of human life. If it were we would have to consider every navvy superior to Shakespeare.

(For a brilliant logician, this is an extraordinarily bad piece of reasoning. An activity could be one of the possible ends of human life without being the only end or the “highest” end. Equally remarkable, though, is the intellectual snobbery the statement betrays, suggesting as it does that writing a play is self-evidently a “superior” goal to any kind of skilled feat of craftsmanship or engineering.) Read more »

“She smelled the way the Taj Mahal looks by moonlight,” and other iconic Raymond Chandler lines

Dan Sheehan in Literary Hub:

Today marks the 133rd anniversary of the birth of Raymond Chandler, patron saint of Los Angeles noir and perhaps the most famous crime fiction writer of all time. Each of his nine novels, from The Big Sleep (1939) to the posthumously published Playback (1953), center around iconic gumshoe Philip Marlowe—Chandler’s wisecracking, whiskey-drinking, tough-as-an-old-boot fictional private investigator so memorably portrayed on screen by (among many, many others) Humphrey Bogart, Elliot Gould, and Robert Mitchum—as he navigates the murky underbelly of the City of Angels. Our sister site CrimeReads has more fascinating Chandler content than you can shake a .32 revolver at, and to mark this auspicious anniversary I thought I’d follow their lead by tracking down (and roughing up) some of his most Raymond Chandler-y lines.

Today marks the 133rd anniversary of the birth of Raymond Chandler, patron saint of Los Angeles noir and perhaps the most famous crime fiction writer of all time. Each of his nine novels, from The Big Sleep (1939) to the posthumously published Playback (1953), center around iconic gumshoe Philip Marlowe—Chandler’s wisecracking, whiskey-drinking, tough-as-an-old-boot fictional private investigator so memorably portrayed on screen by (among many, many others) Humphrey Bogart, Elliot Gould, and Robert Mitchum—as he navigates the murky underbelly of the City of Angels. Our sister site CrimeReads has more fascinating Chandler content than you can shake a .32 revolver at, and to mark this auspicious anniversary I thought I’d follow their lead by tracking down (and roughing up) some of his most Raymond Chandler-y lines.

“I was as hollow and empty as the spaces between stars.”

More here.

The Idea That Trees Talk to Cooperate Is Misleading

Kathryn Flinn in Scientific American:

Trees that communicate, care for one another and foster cooperative communities have captured the popular imagination, most notably in Suzanne Simard’s much-praised book Finding the Mother Tree, soon to be a movie, and in other works like James Cameron’s Avatar, Peter Wohlleben’s The Hidden Life of Trees and Richard Powers’ Pulitzer Prize–winning novel The Overstory.

Trees that communicate, care for one another and foster cooperative communities have captured the popular imagination, most notably in Suzanne Simard’s much-praised book Finding the Mother Tree, soon to be a movie, and in other works like James Cameron’s Avatar, Peter Wohlleben’s The Hidden Life of Trees and Richard Powers’ Pulitzer Prize–winning novel The Overstory.

But many scientists like myself believe these depictions misrepresent ecosystems and harm the cause of conservation.

Do trees really talk? Sure. Plants emit hormones and defense signals. Other plants detect these signals and alter their physiology accordingly. But not all the talk is kind; plants also produce allelochemicals, which poison their neighbors.

More here.

Although neoclassical economics relies on assumptions that should have been discarded long ago, it remains the mainstream orthodoxy

James K. Galbraith in Project Syndicate:

Self-regarding economics departments at prestigious academic institutions no longer bother to teach the history of economic thought – a field that I studied at Yale University in 1977, forever compromising my academic career. Why was the topic abandoned – and even shunned and mocked? Students with a skeptical turn of mind would not be wrong to suspect that it was for scandalous reasons (as when, in past centuries, inconvenient aunts were locked away in garrets).

Self-regarding economics departments at prestigious academic institutions no longer bother to teach the history of economic thought – a field that I studied at Yale University in 1977, forever compromising my academic career. Why was the topic abandoned – and even shunned and mocked? Students with a skeptical turn of mind would not be wrong to suspect that it was for scandalous reasons (as when, in past centuries, inconvenient aunts were locked away in garrets).

The four books reviewed here each uncover parts of the scandal. Three are brand new, and the other, The Corruption of Economics, first appeared in 1994 and was re-issued in 2006. Its principal author, the American economist Mason Gaffney, kept his remarkable pen flowing until passing away last summer at the age of 96.

Robert Skidelsky is a historian, an epic biographer of John Maynard Keynes, and a prolific debater in the United Kingdom’s House of Lords. He calls What’s Wrong with Economics? a “primer,” and it is indeed the most accessible of the four books. Skidelsky’s education in the history of economics resembles my own: a wide reading of the classical authors – Adam Smith, David Ricardo, Karl Marx, and others – followed by those associated with the “neoclassical” or “marginalist” revolution of the 1870s.

More here.

The Anti-universe: Lee Smolin, Tara Shears, and Sabine Hossenfelder discuss why there is so little antimatter

Sympathy for the Devil

Janique Vigier in Bookforum:

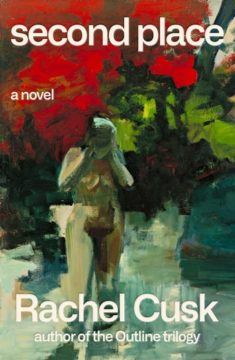

SINCE THE 2014 RELEASE of Outline, the first novel in her acclaimed trilogy, Rachel Cusk has acquired an aura of unimpeachability. This is not to say all reviews of her work have been positive; many invoke the question of “likability,” that awful barometer women are metered against, but the general tone conveys her moral fiber, her strength of character. Not only is her work brilliant, but she herself stands as a kind of moral benchmark. Her position on her themes—womanhood, fate, will, art—has been taken as correct. This is likely in part because she has not come by her reputation easily (attacks on her memoirs, particularly the divorce tale Aftermath, were vicious), nor at a young age (she is now fifty-four).

SINCE THE 2014 RELEASE of Outline, the first novel in her acclaimed trilogy, Rachel Cusk has acquired an aura of unimpeachability. This is not to say all reviews of her work have been positive; many invoke the question of “likability,” that awful barometer women are metered against, but the general tone conveys her moral fiber, her strength of character. Not only is her work brilliant, but she herself stands as a kind of moral benchmark. Her position on her themes—womanhood, fate, will, art—has been taken as correct. This is likely in part because she has not come by her reputation easily (attacks on her memoirs, particularly the divorce tale Aftermath, were vicious), nor at a young age (she is now fifty-four).

Second Place, Cusk’s latest novel, begins from the perch of moral certainty, and never quite lets go. A psychosexual drama with no sex, the book revolves around two characters, referred to only as L and M. L is a male artist, M a female patron. The novel centers around the questions these differences reveal. Or, closer to the truth: these questions and differences reveal Cusk’s predetermined moral universe. Questions are illusory; there are deterministic stances. The standpoint of the main characters reflects this. L, fey and ascetic, is a thinly disguised version of D. H. Lawrence, whom Cusk has called her mentor. L is a painter, not a writer, but the specter of Male Genius is made clear. His foil, M, the writer-narrator, reveres his paintings, seeing him, by extension, as a kind of oracle. She makes the natural assumption and casual error of conflating the virtues of the work with the character of the artist. Cusk’s own devotion to Lawrence makes these metatextual tricks all the more fraught. Is there a more intimate and controlling way to pay homage to your literary idol than by turning him into a fictional character?

It’s a funny time to write a novel about Lawrence, though not necessarily more so than any other: too romantic to be modern, accused by his contemporaries of being a pornographer—that is, part of the avant-garde—he has never been contemporary, not even in his own time. A man whose tragedy, according to Angela Carter, was that “he thought he was a man,” a pious man who wrote frankly about sex, Lawrence suffered his aloneness. Poor, childless, mostly itinerant, he shares little biographical similarity with Cusk, who has turned her children, her career success, and her home into subjects for her fiction. What the two writers do share is a basic and unassailable belief in the individual, a belief that underwrites their obsessive preoccupation with will, intuition, and transformation. Above all it’s women—as question and problem—that drive their work and fetter their hearts. How can women give voice to themselves? What can love look like? And freedom?

More here.

Plants Feel Pain and Might Even See

Peter Wohlleben in Nautilus:

In 2018, a German newspaper asked me if I would be interested in having a conversation with the philosopher Emanuele Coccia, who had just written a book about plants, Die Wurzeln der Welt (published in English as The Life of Plants). I was happy to say yes.

In 2018, a German newspaper asked me if I would be interested in having a conversation with the philosopher Emanuele Coccia, who had just written a book about plants, Die Wurzeln der Welt (published in English as The Life of Plants). I was happy to say yes.

The German title of Coccia’s book translates as “The Roots of the World,” and the book really does cover this. It upends our view of the living world, putting plants at the top of the hierarchy with humans down at the bottom. I had been giving a great deal of thought to this myself. Ranking the natural world and scoring species according to their importance or their superiority seemed to me outdated. It distorts our view of nature and makes all the other species around us seem more primitive and somehow unfinished. For some time now, I have not been comfortable with viewing humans as the crown of creation, separating animals into higher and lower life-forms, and treating plants as something on the side, definitively banished to a lower level.

And so I found the conversation with Coccia most refreshing when he visited our Forest Academy. A small bearded man, Coccia turned up in a blue suit and blue checkered tie, completely inappropriate attire for the outdoors, even though we had agreed that we would take a walk in the forest together. Although he is from Italy and now teaches in France and writes in French, he also speaks fluent German because at one time he studied and worked in Freiburg.

After our first cup of coffee, we were soon deep into our main topic: trees and plants in general. Coccia argued that our biological classifications are not grounded in science. They are strongly influenced by theology and are dominated by two ideas: the supremacy of the human race and the world as a place humans must bend to their will. And then there is our centuries-old compulsion to categorize everything. When you combine these concepts, you get a ranking system that puts humankind at the top, animals in the middle, and plants way down at the bottom.

I listened, fascinated by what he had to say.

More here.

Sunday Poem

Grandmother

my grandmother

doesn’t know pain

she believes that

famine is nutrition

poverty is wealth

thirst is water

her body like a grapevine winding around a walking stick

her hair bees’ wings

she swallows the sun-speckles of pills

and calls the internet the telephone to america

her heart has turned into a rose the only thing you can do

is smell it

pressing yourself to her chest

there’s nothing else you can do with it

only a rose

her arms like stork’s legs

red sticks

and i am on my knees

howling like a wolf

at the white moon of your skull

grandmother

i’m telling you it’s not pain

just the embrace of a very strong god

one with an unshaven cheek that prickles when he kisses you.

by Valzhyna Mortf

from: Factory of Tears

Copper Canyon Press, 2008

Translation from Belarusian: 2008, Valzhyna Mort,

Franz Wright and Elizabeth Oehlkers Wright

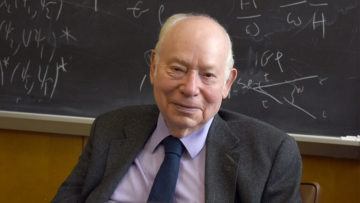

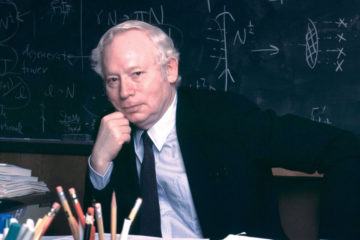

Scott Aaronson remembers Steven Weinberg (1933-2021)

Scott Aaronson in Shtetl-Optimized:

Steven Weinberg was, perhaps, the last truly towering figure of 20th-century physics. In 1967, he wrote a 3-page paper saying in effect that as far as he could see, two of the four fundamental forces of the universe—namely, electromagnetism and the weak nuclear force—had actually been the same force until a tiny fraction of a second after the Big Bang, when a broken symmetry caused them to decouple. Strangely, he had developed the math underlying this idea for the strong nuclear force, and it didn’t work there, but it did seem to work for the weak force and electromagnetism. Steve noted that, if true, this would require the existence of a new particle that hadn’t yet been seen — the Z boson — and would also require the existence of the previously-proposed Higgs boson.

Steven Weinberg was, perhaps, the last truly towering figure of 20th-century physics. In 1967, he wrote a 3-page paper saying in effect that as far as he could see, two of the four fundamental forces of the universe—namely, electromagnetism and the weak nuclear force—had actually been the same force until a tiny fraction of a second after the Big Bang, when a broken symmetry caused them to decouple. Strangely, he had developed the math underlying this idea for the strong nuclear force, and it didn’t work there, but it did seem to work for the weak force and electromagnetism. Steve noted that, if true, this would require the existence of a new particle that hadn’t yet been seen — the Z boson — and would also require the existence of the previously-proposed Higgs boson.

By 1979, enough of this picture (in particular, the Z boson) had been found that Steve shared the Nobel Prize in Physics with Sheldon Glashow—Steve’s former high-school classmate—as well as with Abdus Salam, both of whom had separately developed pieces of the same puzzle. As arguably the central architect of what we now call the Standard Model of elementary particles, Steve was in the ultra-rarefied class where, had he not won the Nobel Prize in Physics, it would’ve been a stain on the Nobel Prize rather than on him.

More here.

Steven Weinberg: To Explain the World

Death of World-Renowned Physicist Steven Weinberg

From UT News:

In 1967, Weinberg published a seminal paper laying out how two of the universe’s four fundamental forces — electromagnetism and the weak nuclear force — relate as part of a unified electroweak force. “A Model of Leptons,” at barely three pages, predicted properties of elementary particles that at that time had never before been observed (the W, Z and Higgs boson) and theorized that “neutral weak currents” dictated how elementary particles interact with one another. Later experiments, including the 2012 discovery of the Higgs boson at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) in Switzerland, would bear out each of his predictions.

Weinberg leveraged his renown and his science for causes he cared deeply about. He had a lifelong interest in curbing nuclear proliferation and served briefly as a consultant for the U.S. Arms Control and Disarmament Agency.

Why Neoliberalism Needs Neofascists

Prabhat Patnaik in Boston Review:

Prabhat Patnaik in Boston Review:

It has been four decades since neoliberal globalization began to reshape the world order. During this time, its agenda has decimated labor rights, imposed rigid limits on fiscal deficits, given massive tax breaks and bailouts to big capital, sacrificed local production for multinational supply chains, and privatized public sector assets at throwaway prices.

The result today is a perverse regime defined by the free movement of capital, which moves relatively effortlessly across international borders, even as free movement of the people is ruthlessly controlled by a sharp increase in income inequality and a steady winnowing of democracy. No matter who comes to power, no matter what promises are made before elections, the same economic policies are followed. Since capital, especially finance, can leave a country en masse at extremely short notice—precipitating an acute financial crisis if its “confidence” in a country is undermined—governments are loath to upset the status quo; they pursue policies favorable to finance capital and indeed demanded by it. The sovereignty of the people, in short, is replaced by the sovereignty of global finance and the domestic corporations integrated with it.

This abridgment of democracy is usually justified by political and economic elites on the grounds that neoliberal economic policies usher in higher GDP growth—considered the summum bonum after which all policy should aim. And indeed, in many countries, especially in Asia, the neoliberal era has ushered in noticeably more rapid growth than under the earlier period of dirigisme. Such growth scarcely benefits the bulk of the people, of course: in fact, neoliberal policies are even more highly associated with the growth of income inequality than with the growth of GDP. (Even International Monetary Fund economists Jonathan D. Ostry, Prakash Loungani, and Davide Furceri concede this point in their 2016 article “Neoliberalism: Oversold?”) But neoliberals have sold a powerful response to this objection: a rise in income inequality should be considered an acceptable price to pay for more rapid growth, for it still might mean an absolute improvement in the conditions of the worst off. The fundamental ideological conceit of neoliberalism has been that growth will lift all boats, even if some boats rise much more than others.

More here.

Path Persistence

Isabella Weber in Phenomenal World:

Isabella Weber in Phenomenal World:

During the first era of globalization (1870–1913), the global division of labor was stark. Britain and other Western nations largely produced manufactured goods, but they also exported a whole range of temperate agricultural goods like wheat, beef and barley. Elsewhere in the European colonial empires, products like cotton, cocoa and coffee were exported, often at very low prices and sometimes with forced labor, to sate a growing demand in the global economic core for tropical luxuries. More than a century has passed since World War I heralded the collapse of this world order. Today, the globalization wave that has shaped the world since the 1980s is ebbing.

What is the legacy of the First Globalization of the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-centuries on the economic fortunes of countries during the Second Globalization? To what extent have countries’ positions in the international economic order been persistent across the two globalizations, with some trapped at the bottom and others comfortably on top?

Long-term development trajectories are commonly explained through the convergence hypothesis. Derived from neoclassical growth theory, it states that “initial conditions have no implications for the long-run distribution of per capita income.” The hypothesis suggests that history has no persistent bearing on countries’ relative wealth: if left to the laws of the market, poorer countries are expected to catch up by outperforming richer countries in their rates of economic growth. However, the convergence hypothesis is not backed by empirical evidence—extensive testing has not heralded the results that standard growth theory would expect. In an effort to elucidate these findings, a quickly growing “persistence literature” has proposed a range of explanations for why countries’ relative wealth today is historically rooted in institutional quality (referring in this case to property rights regimes and liberal representative democracy), culture, religion, geography, or even genetics.

More here.

‘Roadrunner’ and the Dismal Search for the ‘Real Bourdain’

Maria Bustillos in Eater:

Maria Bustillos in Eater:

An obscure, 43-year-old chef and author of minor crime novels is reborn, after a sudden and unexpected literary success, into a life of global fame and influence. A charmed life, cut short when he hanged himself in a hotel bathroom in Alsace 18 years later. This is the story of Roadrunner, the new documentary about the late Anthony Bourdain directed by Morgan Neville.

The film is an elegant montage of interviews with Bourdain’s intimates — chefs David Chang and Eric Ripert, painter David Choe, musicians Josh Homme and John Lurie, Ottavia Busia (his second wife, and the mother of his daughter Ariane), and many others — intercut with images of rock stars, writers, and classic films he admired, and archival footage from a long, strange career in front of the camera. Over the years the boyishly awkward, Rundgrenesquely toothy grin of 1999 gives way to Bourdain’s familiarly friendly, knowing, jaded smile.

Since Bourdain’s death, the desire to get to the Real Truth of Bourdain has been as fervent as his memorialization. In the brave new world of social media influencers and reality TV, an awareness of the artificiality of even the most “authentic” branded personality is taken for granted; maybe more than that, people want — and even need — to know how someone so loved and admired could have slipped beyond the reach of friends, of help. And so the intense drive to understand the space between the genuine Bourdain and the Bourdain on camera grew. What Neville has attempted to do with Roadrunner is to close that gap.

More here.

Julie Mehretu and Shahzia Sikander In Conversation

The Radical Women Who Paved the Way for Free Speech and Free Love

Margaret Talbot in The New Yorker:

Anthony Comstock may be the only man in American history whose lobbying efforts yielded not only the exact federal law he wanted but the privilege of enforcing it to his liking for four decades. Given that Comstock never held elected office and that the highest appointed position he occupied in government was special agent of the Post Office, this was an extraordinary achievement—and a reminder of the ways that zealots have sometimes slipped past the sentries of American democracy to create a reality that the rest of us must live in. Comstock was an anti-vice crusader who worried about many of the things that Americans of a similar moral and religious cast worried about in the late nineteenth century: the rise of the so-called sporting press, which specialized in randy gossip and user guides to local brothels; the phenomenon of young men and women set loose in big cities, living, unsupervised, in cheap rooming houses; the enervating effects of masturbation; the ravages of venereal disease; the easy availability of contraceptives, such as condoms and pessaries, and of abortifacients, dispensed by druggists or administered by midwives. But Comstock railed against all these things more passionately than most of his contemporaries did, and far more effectively.

Anthony Comstock may be the only man in American history whose lobbying efforts yielded not only the exact federal law he wanted but the privilege of enforcing it to his liking for four decades. Given that Comstock never held elected office and that the highest appointed position he occupied in government was special agent of the Post Office, this was an extraordinary achievement—and a reminder of the ways that zealots have sometimes slipped past the sentries of American democracy to create a reality that the rest of us must live in. Comstock was an anti-vice crusader who worried about many of the things that Americans of a similar moral and religious cast worried about in the late nineteenth century: the rise of the so-called sporting press, which specialized in randy gossip and user guides to local brothels; the phenomenon of young men and women set loose in big cities, living, unsupervised, in cheap rooming houses; the enervating effects of masturbation; the ravages of venereal disease; the easy availability of contraceptives, such as condoms and pessaries, and of abortifacients, dispensed by druggists or administered by midwives. But Comstock railed against all these things more passionately than most of his contemporaries did, and far more effectively.

Nassau Street, at the lower tip of Manhattan, was a particular horror to him—a groaning board of Boschian temptations. As Amy Sohn details in her fascinating book “The Man Who Hated Women: Sex, Censorship & Civil Liberties in the Gilded Age” (Farrar, Straus & Giroux), when Comstock arrived in New York as a young man, just after the Civil War, he was appalled to see an open market in sex toys and contraceptive devices (both often hawked as “rubber goods”), along with smutty playing cards, books, and stereoscopic images. At the wholesale notions establishment where he held a job, Comstock lamented that the young men he worked with were “falling like autumn leaves about me from the terrible scourges of vile books and pictures.”

More here.

I don’t: my very modern marriage

Anna Baddeley in 1843 Magazine:

You can hold hands if you want to.” We had arrived at the part in our ceremony where we had to parrot a legal declaration, and the registrar was clearly desperate to inject some romance into proceedings.

You can hold hands if you want to.” We had arrived at the part in our ceremony where we had to parrot a legal declaration, and the registrar was clearly desperate to inject some romance into proceedings.

In June, my partner and I were bound together in the eyes of the British state. We didn’t get married though – we got a civil partnership, a type of union invented for gay couples in 2004 that was recently opened up to straight couples after a long campaign to change the law. We had opted for a pared-down ceremony, with no guests apart from the two friends who were acting as our witnesses. The venue was Room 99, the cheapest space to get married at Islington Town Hall in north London. “I’d rather not hold his hand,” I said. “Mine are too sweaty.” The registrar apologised, worried she had offended me. I hadn’t meant to make her feel awkward, but I’m one of those people who instinctively makes a joke when put in an uncomfortable situation. And I was keen for the ceremony to be as unromantic as possible. We were doing this not for love, but for tax.

The social and economic rationale behind marriage used to be clear: sanctified, legal reproduction; a business deal between two families. Now that the feudal backdrop has disappeared, people get married for more waffly reasons. For most millennials, it’s merely an excuse for a party. When marriage is seen purely as a celebration of love, the legal and financial benefits are obscured. I suspect few of my friends got married because of the tax breaks, but in Britain marriage can reduce your income-tax bill, capital-gains tax and the inheritance tax your children have to pay (you also get automatic status as the next of kin in times of crisis and the right to claim some of your spouse’s money if you break up).

More here.