#Film4Climate 1st Prize Short Film Winner – “Three Seconds” from Connect4Climate on Vimeo.

Month: July 2021

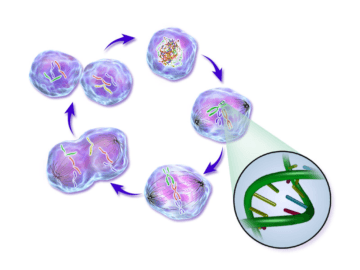

Discovery of Tumor Suppressor Suggests New Cancer Treatment Strategies

NCI Staff in Cancer.gov:

At the heart of all cancers is a fundamental problem: a cell—and eventually innumerable cells—that won’t stop dividing. This runaway growth is what forms a tumor, and the abnormal cellular processes that drive this growth can help tumors withstand the cancer treatments intended to kill them. Despite more than six decades of research into the mechanisms that cells use to divide, some of the nuts and bolts of the process remain a mystery. Scientists want to better understand these mechanisms in hopes of targeting them and potentially shutting down the uncontrolled growth of some tumors. New research from three collaborating teams of scientists in the United States and Europe appears to have found one of these mechanisms, uncovering a previously unknown check on dividing cells: a protein called AMBRA1. By limiting tumor growth, the researchers showed, AMBRA1 serves as an important tumor suppressor—as these types of molecules are often called—in healthy cells.

At the heart of all cancers is a fundamental problem: a cell—and eventually innumerable cells—that won’t stop dividing. This runaway growth is what forms a tumor, and the abnormal cellular processes that drive this growth can help tumors withstand the cancer treatments intended to kill them. Despite more than six decades of research into the mechanisms that cells use to divide, some of the nuts and bolts of the process remain a mystery. Scientists want to better understand these mechanisms in hopes of targeting them and potentially shutting down the uncontrolled growth of some tumors. New research from three collaborating teams of scientists in the United States and Europe appears to have found one of these mechanisms, uncovering a previously unknown check on dividing cells: a protein called AMBRA1. By limiting tumor growth, the researchers showed, AMBRA1 serves as an important tumor suppressor—as these types of molecules are often called—in healthy cells.

The new work shows that AMBRA1 marks other proteins involved in helping cells divide (known as cyclins) for destruction when cell division isn’t needed. When the gene that produces AMBRA1 is damaged and the protein is missing or doesn’t work properly, the cell cycle loses one of its main brakes, potentially letting cell division spiral out of control. The loss of the AMBRA1 protein, the researchers found, can drive tumor formation in mice and is linked with worse outcomes in some human tumors. They also reported that a lack of AMBRA1 may make some tumors resistant to drugs called CDK4/6 inhibitors, which are a promising new class of cancer treatments. The new research may point to potential strategies for blocking the runaway cell division caused by loss of AMBRA1 and for re-sensitizing cancer cells to CDK4/6 inhibitors. The results from all three studies were published on April 14 in Nature.

More here.

A New Era of Designer Babies May Be Based on Overhyped Science

Laura Hercher in Scientific American:

For better or worse, genetic testing of embryos offers a potential gateway into a new era of human control over reproduction. Couples at risk of having a child with a severe or life-limiting disease such as cystic fibrosis or Duchenne muscular dystrophy have used preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) for decades to select among embryos created through in vitro fertilization (IVF) for those that do not carry the disease-causing gene. But what new iteration of genetic testing could tempt healthy, fertile couples to reject our traditional time-tested and wildly popular process of baby making in favor of hormone shots, egg extractions and DNA analysis?

For better or worse, genetic testing of embryos offers a potential gateway into a new era of human control over reproduction. Couples at risk of having a child with a severe or life-limiting disease such as cystic fibrosis or Duchenne muscular dystrophy have used preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) for decades to select among embryos created through in vitro fertilization (IVF) for those that do not carry the disease-causing gene. But what new iteration of genetic testing could tempt healthy, fertile couples to reject our traditional time-tested and wildly popular process of baby making in favor of hormone shots, egg extractions and DNA analysis?

A California-based start-up called Orchid Biosciences claims it has an answer to that question. The company offers prospective parents genetic testing prior to conception to calculate risk scores estimating their own likelihood of confronting common illnesses such as heart disease, diabetes, and schizophrenia and the likelihood that they will pass such risks along to a future child. Parents-to-be can then use IVF, along with Orchid’s upcoming embryo screening package, to identify the healthiest of their embryos for a pregnancy.

Orchid aims to use PGT and IVF to expand what is already a thriving marketplace in screening tests for prospective parents. Initially, the only people offered tests to prevent genetic disease in the next generation were those whose ancestry put them at higher risk for a specific condition, such as Tay-Sachs disease in the Ashkenazi Jewish population. The first genetic screen intended for universal use and covering a wide range of diseases was introduced by Counsyl (now part of Myriad Genetics) in 2010. Today carrier screening is a $1.7-billion industry. These tests search for genetic problems that otherwise come to light only after the birth of an affected child. But diseases caused by a single gene are rare. Most children are born healthy, and most couples who do carrier screening come away reassured.

More here.

William Morris: The Poetics of Indigo Discharge Printing

Caroline Arscott at nonsite:

The systems featured in Morris’s designs often suggest conflict and attrition at the micro level along with harmony at the grander scale. Within the system of the design, principles of growth relate to his conception of the forces of nature and history. He constructed his designs to mirror and even exceed the powerful generative abilities of nature; he also intended them to be vectors for the energies of history.

The systems featured in Morris’s designs often suggest conflict and attrition at the micro level along with harmony at the grander scale. Within the system of the design, principles of growth relate to his conception of the forces of nature and history. He constructed his designs to mirror and even exceed the powerful generative abilities of nature; he also intended them to be vectors for the energies of history.

Morris includes feeding rabbits in his textile print Brother Rabbit: he gives them as beneficiaries and examples of nature’s plenty (fig. 2). They feed, they grow, they multiply. He referenced natural forms, vegetal and animal, and sought to infuse these natural elements with a sense of life and growth—not for him the deathly display of elements technically “natural” but in some designers’ hands lacking the appearance of life. Like the biologists investigating cell structure and protoplasm he found a commonality in all living things. This allowed or obliged him to undo the fence around the domain of the design, to broaden the horizons, to allegorise and to visualise a macro-system. By the 1880s this system relates to history and society understood from the perspective of communist theory.

more here.

Turkish Electro Funk Güzel Mix

Viral Photos

Dushko Petrovich at n+1:

I kept looking at the recently infamous—now half-forgotten—picture of the Bidens visiting the Carters. The photo was taken and passed around feverishly almost two months ago, when I saw it repeatedly on my scroll and dragged the file onto my desktop, and I haven’t been able to forget it since. Everyone else moved on to Joyce Carol Oates negging Mad Men, Elon Musk going on SNL, Bennifer 2.0, and a bunch of other things I’m forgetting, but here I am, late at night, still staring at little Rosalynn, little Jimmy, big Jill, and big Joe. Also the armchairs, the blue-green walls, the blue-blue carpeting, the “unfinished” cameo-style paintings of the Carters, the blank canvas keyed to the off-white upholstery of their chairs. I’ve reviewed the institutional sheen on those cabinets, zoomed in on the trio of mask-like ceramics facing up to the ceiling on the side table, pondered the bulbous bronze bookends holding a three-volume set of something important on that same table. But mostly I’ve been staring at the little Carters and the big Bidens, trying to understand what is so transfixing to me there. And I think I finally have an answer. So at the risk of disrespecting the immutable orientation of our media universe, I want to return to the topic that was on everyone’s minds on May 3, 2021. I want to turn and watch the sunset.

I kept looking at the recently infamous—now half-forgotten—picture of the Bidens visiting the Carters. The photo was taken and passed around feverishly almost two months ago, when I saw it repeatedly on my scroll and dragged the file onto my desktop, and I haven’t been able to forget it since. Everyone else moved on to Joyce Carol Oates negging Mad Men, Elon Musk going on SNL, Bennifer 2.0, and a bunch of other things I’m forgetting, but here I am, late at night, still staring at little Rosalynn, little Jimmy, big Jill, and big Joe. Also the armchairs, the blue-green walls, the blue-blue carpeting, the “unfinished” cameo-style paintings of the Carters, the blank canvas keyed to the off-white upholstery of their chairs. I’ve reviewed the institutional sheen on those cabinets, zoomed in on the trio of mask-like ceramics facing up to the ceiling on the side table, pondered the bulbous bronze bookends holding a three-volume set of something important on that same table. But mostly I’ve been staring at the little Carters and the big Bidens, trying to understand what is so transfixing to me there. And I think I finally have an answer. So at the risk of disrespecting the immutable orientation of our media universe, I want to return to the topic that was on everyone’s minds on May 3, 2021. I want to turn and watch the sunset.

more here.

Friday Poem

Maybe to you too

Billionaires such as Musk, Bezos, and Branson peddle the idea that space represents a public hope, all the while reaping big private profits

Alina Utrata in the Boston Review:

Having made enormous fortunes on Earth, billionaires are now racing each other to space. Former Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos, the richest person on the planet, recently announced that he will be one of four “space tourists” on his private space company Blue Origin’s inaugural human spaceflight scheduled for July 20, 2021, the anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing. The news caused Virgin Galactic owner Richard Branson to speed up his own planned space trip and launch himself into space this weekend, nine days before Bezos.

Fellow tech billionaire, and third richest person on Earth, Elon Musk is often the most vocal about his space company, SpaceX, and his plans to make humans an “interplanetary species.” Bezos, however, is just as obsessed with outer space as the Tesla founder is. The billionaires concur that it is humanity’s destiny to settle the stars. And, without much real public debate, private space corporations appear to have settled the matter: space will be humanity’s next frontier.

The notion that private corporations ought to achieve something that states have been able to do since the 1960s—fly to space—is a peculiarly U.S. one. It combines domestic libertarianism and its idolatry of private individuals’ entrepreneurship with the more global ethos of neoliberalism and government outsourcing. However, despite these motivating philosophies, private companies have launched their schemes for space colonization using massive amounts of public money through government contracts.

More here.

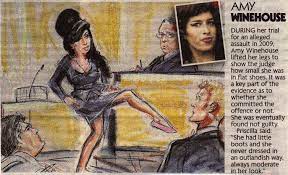

Courtroom Sketches

Hatty Nestor at Granta:

Society loves courtroom dramas – they allow the viewer to consume the uncertainty of someone else’s life as opposed to fixating on their own. (I am as guilty of this as anyone: I’ve watched courtroom dramas every week religiously in the past, especially Primal Fear and The Lincoln Lawyer.) We get hooked on the interrelations of characters, the impending catastrophe, the emotional mind games played by the press, lawyers, and bogeymen criminals. The allure of the genre, I believe, has to do with the hidden nature of the legal scenario. Films, television shows, and podcasts purport to expose the mystery of the courtroom, and the private lives of those tangled up in its web.

Society loves courtroom dramas – they allow the viewer to consume the uncertainty of someone else’s life as opposed to fixating on their own. (I am as guilty of this as anyone: I’ve watched courtroom dramas every week religiously in the past, especially Primal Fear and The Lincoln Lawyer.) We get hooked on the interrelations of characters, the impending catastrophe, the emotional mind games played by the press, lawyers, and bogeymen criminals. The allure of the genre, I believe, has to do with the hidden nature of the legal scenario. Films, television shows, and podcasts purport to expose the mystery of the courtroom, and the private lives of those tangled up in its web.

Beyond courtroom dramas and ‘true crime’ stories of trials, such as Dateline, American Crime Story, Killing Fields, and my recent favourite, Netflix’s The Staircase, the courtroom sketch is a key example of how the goings-on at trial are represented and disseminated. Notable cases that have been illustrated include Amy Winehouse’s 2009 trial for assault after she was accused of hitting a woman at a charity ball. A drawing by sketch artist Priscilla Coleman shows Winehouse extending her leg and hitching up her dress, in order to demonstrate to the court her slight frame as evidence of her innocence.

more here.

Radiohead’s Eerie Creep Remix

George Eaton at The New Statesman:

“Creep” was subsequently excised from the band’s set list – “Fuck off, we’re tired of it,” Yorke explained to a Montreal audience – and now, like a submarine, only surfaces at rare junctures (Reading Festival 2009, Glastonbury 2016). Now Radiohead have added a new chapter to the “Creep” chronicles. On 13 July, Yorke released a remixed version of the song “Creep (Very 2021 Rmx)” for “a world that is seemingly turning upside down”. The track, which was first used to soundtrack a Japanese fashion show in March of this year, sees an earlier acoustic version stretched from four minutes to nine by means of a radically slowed tempo. Faced with this, both admirers and detractors of “Creep” might reasonably ask: what the hell are they doing here? The first verse alone is two minutes long and, aside from some electronic burblings, is rather underwhelming (unless deathly slow strumming is your thing).

“Creep” was subsequently excised from the band’s set list – “Fuck off, we’re tired of it,” Yorke explained to a Montreal audience – and now, like a submarine, only surfaces at rare junctures (Reading Festival 2009, Glastonbury 2016). Now Radiohead have added a new chapter to the “Creep” chronicles. On 13 July, Yorke released a remixed version of the song “Creep (Very 2021 Rmx)” for “a world that is seemingly turning upside down”. The track, which was first used to soundtrack a Japanese fashion show in March of this year, sees an earlier acoustic version stretched from four minutes to nine by means of a radically slowed tempo. Faced with this, both admirers and detractors of “Creep” might reasonably ask: what the hell are they doing here? The first verse alone is two minutes long and, aside from some electronic burblings, is rather underwhelming (unless deathly slow strumming is your thing).

more here.

Creep Remix

Human genetic variants identified that affect COVID susceptibility and severity

Samira Asgari and Lionel A. Pousaz in Nature:

For more than a year now, scientists and clinicians have been trying to understand why some people develop severe COVID-19 whereas others barely show any symptoms. Risk factors such as age and underlying medical conditions1, and environmental factors including socio-economic determinants of health2, are known to have roles in determining disease severity. However, variations in the human genome are a less-investigated source of variability. Writing in Nature, members of the COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative3 (www.covid19hg.org) report results of a large human genetic study of SARS-CoV-2 infection. The researchers identify 13 locations (or loci) in the human genome that affect COVID-19 susceptibility and severity.

For more than a year now, scientists and clinicians have been trying to understand why some people develop severe COVID-19 whereas others barely show any symptoms. Risk factors such as age and underlying medical conditions1, and environmental factors including socio-economic determinants of health2, are known to have roles in determining disease severity. However, variations in the human genome are a less-investigated source of variability. Writing in Nature, members of the COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative3 (www.covid19hg.org) report results of a large human genetic study of SARS-CoV-2 infection. The researchers identify 13 locations (or loci) in the human genome that affect COVID-19 susceptibility and severity.

More here.

Mark Blyth: Why does inflation worry the right so much?

Mark Blyth in The Guardian:

Thirty years ago, Albert O Hirschman published a short book that infuriated conservatives called The Rhetoric of Reaction. The book showed how conservative arguments across time and space fell into three rhetorical buckets: perversity – raising taxes means less revenue; futility – voting changes nothing; and jeopardy – if you give the vote to poor people, you get revolution (the opposite of futility, but who cares about consistency). As well as being a great summer read, Hirschman’s rhetoric continues to shed a useful light on the present conservative obsession (apart from critical race theory) with inflation.

Thirty years ago, Albert O Hirschman published a short book that infuriated conservatives called The Rhetoric of Reaction. The book showed how conservative arguments across time and space fell into three rhetorical buckets: perversity – raising taxes means less revenue; futility – voting changes nothing; and jeopardy – if you give the vote to poor people, you get revolution (the opposite of futility, but who cares about consistency). As well as being a great summer read, Hirschman’s rhetoric continues to shed a useful light on the present conservative obsession (apart from critical race theory) with inflation.

Whenever inflation threatens, two versions of the perversity thesis are deployed. The first, usually opined by members of the investor class, argues that inflation mainly hits those on fixed incomes, older and poorer people, thereby proving their concern is born from a sense of care for society’s weakest. Oddly, that same class of folks seem utterly indifferent to older and poorer people until inflation threatens to either reduce their expected investment returns, or impact their leveraged financial strategies, as interest rates rise.

More here.

How a dragonfly’s brain is designed to kill

Hell is other people: a monk’s guide to office life

Catherine Nixy in 1843 Magazine:

Over the past year many of us have sat at home, confined to the same four walls for much of the day, contemplating the same view, munching the same lunch and wearing the same clothes (at least below waist level). While the key workers of the world actually kept everything running by going out to work, many of us have likened our privileged isolation to that of a monk confined in a monastery, world at bay. The word “monk” comes from a Greek word meaning “alone”, which is exactly how monks spent their earliest days, living and working anywhere from the sands of the Syrian desert to the banks of the River Nile. One particularly celebrated figure spent almost 40 years standing on a pillar in Syria until his feet exploded and his spine collapsed. (Those missing their ergonomic office chairs may sympathise.)

Over the past year many of us have sat at home, confined to the same four walls for much of the day, contemplating the same view, munching the same lunch and wearing the same clothes (at least below waist level). While the key workers of the world actually kept everything running by going out to work, many of us have likened our privileged isolation to that of a monk confined in a monastery, world at bay. The word “monk” comes from a Greek word meaning “alone”, which is exactly how monks spent their earliest days, living and working anywhere from the sands of the Syrian desert to the banks of the River Nile. One particularly celebrated figure spent almost 40 years standing on a pillar in Syria until his feet exploded and his spine collapsed. (Those missing their ergonomic office chairs may sympathise.)

From the fourth century onwards, the great monkish wfh experiment fell out of fashion and monks flooded into monasteries – just as many employers hope their staff will do this summer, as life reverts to some semblance of its before-covid (bc) self.

A monastic life may sound surprisingly familiar. They put on drab work clothes each day to turn up for duty, same time, same place. They embraced the nine to five (or, to be precise, the 6am to 7pm. Tough boss). If going back to the office reminds you how annoying your colleagues are, spare a thought for the monks who had the same ones – and endured their same noxious habits – until the day they died (and, assuming they’d laid their bet in Pascal’s wager correctly, after it, too). If you hated the way your tablemate slurped his soup or sang evensong, you simply had to keep quiet and offer up your suffering to God.

Once monks gave up their flexi-work freedoms they had to find a way to get along with their brethren. Judging by the outpouring of literature spawned by this move, as soon as corporate monkish life began, brothers started to annoy each other.

More here.

How to Unlearn a Disease

Kelly Clancy in Nautilus:

My father, a neurologist, once had a patient who was tormented, in the most visceral sense, by a poem. Philip was 12 years old and a student at a prestigious boarding school in Princeton, New Jersey. One of his assignments was to recite Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven. By the day of the presentation, he had rehearsed the poem dozens of times and could recall it with ease. But this time, as he stood before his classmates, something strange happened. Each time he delivered the poem’s famous haunting refrain—“Quoth the Raven ‘Nevermore’ ”—the right side of his mouth quivered. The tremor intensified until, about halfway through the recitation, he fell to the floor in convulsions, having lost all control of his body, including bladder and bowels, in front of an audience of merciless adolescents. His first seizure.

My father, a neurologist, once had a patient who was tormented, in the most visceral sense, by a poem. Philip was 12 years old and a student at a prestigious boarding school in Princeton, New Jersey. One of his assignments was to recite Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven. By the day of the presentation, he had rehearsed the poem dozens of times and could recall it with ease. But this time, as he stood before his classmates, something strange happened. Each time he delivered the poem’s famous haunting refrain—“Quoth the Raven ‘Nevermore’ ”—the right side of his mouth quivered. The tremor intensified until, about halfway through the recitation, he fell to the floor in convulsions, having lost all control of his body, including bladder and bowels, in front of an audience of merciless adolescents. His first seizure.

When my father heard this story, he decided to try an experiment. During Philip’s initial visit, he handed the boy a copy of The Raven and asked him to read it aloud. Again, at each utterance of the raven’s gloomy prophecy, Philip stuttered. His teeth clenched and his lips pulled sideward as though he were disagreeing with something that had been said. My father took the poem away before Philip had a full-blown fit. He wrote a note to the boy’s teacher excusing him from ever having to recite another piece of writing. His brain, my father explained, had begun to associate certain language patterns with the onset of a seizure.

The power of the nervous system lies in this ability to learn, even through adulthood. Networks of neurons discover new relationships through the timing of electrochemical impulses called spikes, which neurons use to communicate with one another. This temporal pattern strengthens or weakens connections between cells, constituting the physical substrate of a memory. Most of the time, the upshot is beneficial. The ability to associate causes with effects—encroaching shadows with dive-bombing falcons, cacti with hidden water sources—gives organisms a leg up on predators and competitors.

But sometimes neurons are too good at their jobs. The brain, with its extraordinary computational prowess, can learn language and logic. It can also learn how to be sick.

More here.

Thursday Poem

Girl of Water, I Could Swallow a Garden

engulf any overgrown plot in an afternoon

with my two ungloved hands

tear every undesirable by the root—

pile their light bodies neatly in the barrow.

I remember standing in a field of men at the botanical garden

holding my shining spade. I remember

what the frat boy doing community service

said to me when I told him to plant.

The sweet potato vines winced,

waved their purple leaves from small, black pots.

There is a photograph my father captured

when visiting: me roaming

those grounds I mulched & culled & greenhoused:

long-limbed slip of me,

doe-eyed by the ponds, a girl

full of yellowing waterlilies,

a green image left on paper.

My father has stopped photographing light,

misremembers my name, disappears me.

Now there are trees in that Carolina city

I planted that are twice, three times as tall

as my sons. Now I am so far from the red

dust and fire

ants that bit my skin every day.

People say I used to go around asking for smoke,

say I used to wander through the camellia collection

following boys who carried instruments.

I say I remember riding in the truck looking for coyote

on coffee breaks with Joey, I

remember the one true line I wrote

in those years of landscape and heat:

I’m really a poet. I’m just here for the snakes.

by Natalie Solmer

from the Echotheo Review

The Magic of Visual Storytelling

Stuff Nick Hornby’s Been Reading

Nick Hornby at The Believer:

I have said it before, probably irritatingly, and I will say it again several more times: one of the most remarkable literary projects of this century is being undertaken right now, as we speak, by the social historian David Kynaston. Since 2007 he has been publishing a series of books about Britain between the years 1945 and 1979, when Margaret Thatcher came to power. There have been three so far: Austerity Britain: 1945–51, Family Britain: 1951–57, and Modernity Britain: 1957–1962—roughly 2,300 pages, or 135 pages per year. If you are going to treat a country as a person, full of personality, development, joy, tragedy, regression, and contradictions—and that is what Kynaston does—then an allocation of 135 per year is actually pretty disciplined. (If, in the year 2070, someone embarks on a similar project, then the year 2020 will demand several hundred thousand words of its own.) These wonderful books deal with politics and town planning, sport and literature, music and movies, cities and the countryside, and a rather gripping narrative somehow emerges, in the same way that improvising jazz soloists find melodies.

I have said it before, probably irritatingly, and I will say it again several more times: one of the most remarkable literary projects of this century is being undertaken right now, as we speak, by the social historian David Kynaston. Since 2007 he has been publishing a series of books about Britain between the years 1945 and 1979, when Margaret Thatcher came to power. There have been three so far: Austerity Britain: 1945–51, Family Britain: 1951–57, and Modernity Britain: 1957–1962—roughly 2,300 pages, or 135 pages per year. If you are going to treat a country as a person, full of personality, development, joy, tragedy, regression, and contradictions—and that is what Kynaston does—then an allocation of 135 per year is actually pretty disciplined. (If, in the year 2070, someone embarks on a similar project, then the year 2020 will demand several hundred thousand words of its own.) These wonderful books deal with politics and town planning, sport and literature, music and movies, cities and the countryside, and a rather gripping narrative somehow emerges, in the same way that improvising jazz soloists find melodies.

more here.

The Adapted Words of Memmie Le Blanc

Karl Steel in Lapham’s Quarterly:

James Burnett, Lord Monboddo, rich, strange, and Scottish, died at eighty-four in 1799. He was known for exposing himself: he exercised naked before the open windows of his estate and eschewed travel by carriage, insisting instead on riding his horse Alburac through the damp gray of every Scottish season. Like many other men of his ilk and era—Rousseau, Condillac, Mandeville—he speculated at length about language’s origins among our primeval ancestors. He maintained, incorrectly but not unlaudably, that fully articulate speech first appeared in the Black civilization of ancient Egypt; that certain Native American languages were mutually intelligible with Gaelic; and, most notoriously, that orangutans were humans, though just too lazy to learn to speak. For Rousseau orangutans’ humanity was only a hypothesis, but Monboddo asserted it as fact so insistently that the universal wit Samuel Johnson likened him to a man with a tail, but without the shame to try to hide it.

James Burnett, Lord Monboddo, rich, strange, and Scottish, died at eighty-four in 1799. He was known for exposing himself: he exercised naked before the open windows of his estate and eschewed travel by carriage, insisting instead on riding his horse Alburac through the damp gray of every Scottish season. Like many other men of his ilk and era—Rousseau, Condillac, Mandeville—he speculated at length about language’s origins among our primeval ancestors. He maintained, incorrectly but not unlaudably, that fully articulate speech first appeared in the Black civilization of ancient Egypt; that certain Native American languages were mutually intelligible with Gaelic; and, most notoriously, that orangutans were humans, though just too lazy to learn to speak. For Rousseau orangutans’ humanity was only a hypothesis, but Monboddo asserted it as fact so insistently that the universal wit Samuel Johnson likened him to a man with a tail, but without the shame to try to hide it.

The Scotsman should be remembered less indulgently for attempting, in 1778, to thwart the successful suit for liberty of Joseph Knight, an enslaved man brought by John Wedderburn from Jamaica to what Knight and his supporters maintained was the free soil of Scotland. Johnson’s friend and future biographer, the Scottish lawyer James Boswell, wrote to Johnson to inform him of the outcome. Eight judges ruled for Knight’s freedom—and with it the end of slavery in Scotland. Four ruled against it, including Monboddo, who, as Boswell reported, maintained that slavery should be honored as lawful, as it was present “in all ages and all countries, and that when freedom flourished, as in old Greece and Rome.” The classical pomp of Monboddo’s legal logic perhaps rested on more local foundations: his desire to keep his mastery over a Black man he called Gory.

More here.