From Prospect:

If the last 18 months haven’t got you thinking, then thinking probably isn’t your thing. We have witnessed microbes’ revenge on civilisation, seen the limits of the “politically possible” being reset and come to revere vaccinologists. We have learned how an economy can keep going after “business as usual” stops, and endured an enforced pause in which we could reconsider life’s priorities. Some of us were conscripted into teaching our children. Some may even have got round to reading the books they had always meant to. Many others didn’t, and got lost instead in armchair epidemiology.

If the last 18 months haven’t got you thinking, then thinking probably isn’t your thing. We have witnessed microbes’ revenge on civilisation, seen the limits of the “politically possible” being reset and come to revere vaccinologists. We have learned how an economy can keep going after “business as usual” stops, and endured an enforced pause in which we could reconsider life’s priorities. Some of us were conscripted into teaching our children. Some may even have got round to reading the books they had always meant to. Many others didn’t, and got lost instead in armchair epidemiology.

There has been plenty to think about—but what sorts of thought are most important in a world emerging from a pandemic? In consultation with the experts who write for us, Prospect presents the world’s top 50 thinkers for this moment. In lively and occasionally heated discussions about who should make the grade, our criteria were not only originality and eminence within a field, but the singular pursuit of an identifiable idea and an ability to gain traction for it. We also insisted on some form of “intervention”—be it a book, speech or a public stand—over the past 12 months.

More here.

It’s not easy, figuring out the fundamental laws of physics. It’s even harder when your chosen methodology is to essentially start from scratch, positing a simple underlying system and a simple set of rules for it, and hope that everything we know about the world somehow pops out. That’s the project being undertaken by Stephen Wolfram and his collaborators, who are working with a kind of discrete system called “hypergraphs.” We talk about what the basic ideas are, why one would choose this particular angle of attack on fundamental physics, and how ideas like quantum mechanics and general relativity might emerge from this simple framework.

It’s not easy, figuring out the fundamental laws of physics. It’s even harder when your chosen methodology is to essentially start from scratch, positing a simple underlying system and a simple set of rules for it, and hope that everything we know about the world somehow pops out. That’s the project being undertaken by Stephen Wolfram and his collaborators, who are working with a kind of discrete system called “hypergraphs.” We talk about what the basic ideas are, why one would choose this particular angle of attack on fundamental physics, and how ideas like quantum mechanics and general relativity might emerge from this simple framework. Just as the pandemic was gathering pace in early 2020, French President

Just as the pandemic was gathering pace in early 2020, French President  The summer that I did my chaplaincy internship was a wildly full twelve weeks. I was thirty-two years old and living in the haze of the end of an engagement as I walked the hospital corridors carrying around my Bible and visiting patients. “Hi, I’m Vanessa. I’m from the spiritual care department. How are you today?” It was a surreal summer full of new experiences hitting like a tsunami: you saw them coming but that didn’t mean you could outrun them. But the thing that never felt weird was that the Bible I carried around with me as I went to visit patient after patient, that I turned to in the guest room at David and Suzanne’s or on my parents’ couch to sustain me, was a nineteenth-century gothic Romance novel. The Bible I carried around that busy summer was Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre.

The summer that I did my chaplaincy internship was a wildly full twelve weeks. I was thirty-two years old and living in the haze of the end of an engagement as I walked the hospital corridors carrying around my Bible and visiting patients. “Hi, I’m Vanessa. I’m from the spiritual care department. How are you today?” It was a surreal summer full of new experiences hitting like a tsunami: you saw them coming but that didn’t mean you could outrun them. But the thing that never felt weird was that the Bible I carried around with me as I went to visit patient after patient, that I turned to in the guest room at David and Suzanne’s or on my parents’ couch to sustain me, was a nineteenth-century gothic Romance novel. The Bible I carried around that busy summer was Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre. A University of Alberta-led research study followed more than 400 infants from the CHILD Cohort Study (CHILD) at its Edmonton site. Boys at one year of age with a gut bacterial composition that was high in the bacteria Bacteroidetes were found to have more advanced cognition and language skills one year later. The finding was specific to male children. “It’s well known that female children score higher (at early ages), especially in cognition and language,” said Anita Kozyrskyj, a professor of pediatrics at the U of A and principal investigator of the SyMBIOTA (Synergy in Microbiota) laboratory. “But when it comes to gut microbial composition, it was the

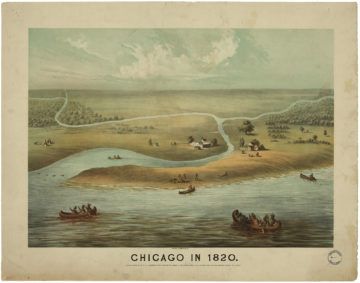

A University of Alberta-led research study followed more than 400 infants from the CHILD Cohort Study (CHILD) at its Edmonton site. Boys at one year of age with a gut bacterial composition that was high in the bacteria Bacteroidetes were found to have more advanced cognition and language skills one year later. The finding was specific to male children. “It’s well known that female children score higher (at early ages), especially in cognition and language,” said Anita Kozyrskyj, a professor of pediatrics at the U of A and principal investigator of the SyMBIOTA (Synergy in Microbiota) laboratory. “But when it comes to gut microbial composition, it was the  So, Chicago’s leaders got creative. Instead of putting sewers under the streets, they put sewers on top of the streets, then built new roads atop the old ones. They effectively hoisted the city out of the swamp.

So, Chicago’s leaders got creative. Instead of putting sewers under the streets, they put sewers on top of the streets, then built new roads atop the old ones. They effectively hoisted the city out of the swamp. We all know the story by now. The “culture wars” used to only be fought in America. In Britain, party support was strongly linked to views on an economic left-right axis; if you believed in extensive government intervention and redistribution then you voted Labour, if you believed in a small state and leaving markets to their own devices, you voted Conservative. But in the last decade, beliefs around values and identity have become increasingly important in UK as well as American politics—at the last UK general election, a voter’s position on values (for example whether they thought the death penalty should be reintroduced) was just as likely to determine their vote as their position on economics.

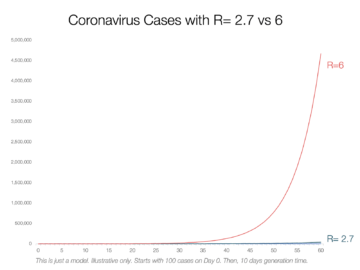

We all know the story by now. The “culture wars” used to only be fought in America. In Britain, party support was strongly linked to views on an economic left-right axis; if you believed in extensive government intervention and redistribution then you voted Labour, if you believed in a small state and leaving markets to their own devices, you voted Conservative. But in the last decade, beliefs around values and identity have become increasingly important in UK as well as American politics—at the last UK general election, a voter’s position on values (for example whether they thought the death penalty should be reintroduced) was just as likely to determine their vote as their position on economics. The original Coronavirus variant has an

The original Coronavirus variant has an  Identities are dangerous and paradoxical things. They are the beginning and the end of the self. They are how we define ourselves and how we are defined by others. One is a “nerd” or a “jock” or a “know-it-all.” One is “liberal” or “conservative,” “religious” or “secular,” “white” or “black.” Identities are the means of escape and the ties that bind. They direct our thoughts. They are modes of being. They are an ingredient of the self—along with relationships, memories, and role models—and they can also destroy the self. Consume it. The Jungians are right when they say people don’t have identities, identities have people. And the Lacanians are righter still when they say that our very selves—our wishes, desires, thoughts—are constituted by other people’s wishes, desires, and thoughts. Yes, identities are dangerous and paradoxical things. They are expressions of inner selves, and a way the outside gets in.

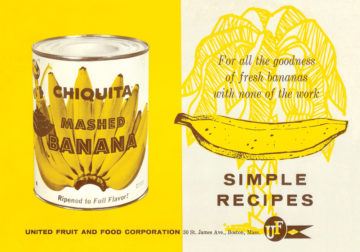

Identities are dangerous and paradoxical things. They are the beginning and the end of the self. They are how we define ourselves and how we are defined by others. One is a “nerd” or a “jock” or a “know-it-all.” One is “liberal” or “conservative,” “religious” or “secular,” “white” or “black.” Identities are the means of escape and the ties that bind. They direct our thoughts. They are modes of being. They are an ingredient of the self—along with relationships, memories, and role models—and they can also destroy the self. Consume it. The Jungians are right when they say people don’t have identities, identities have people. And the Lacanians are righter still when they say that our very selves—our wishes, desires, thoughts—are constituted by other people’s wishes, desires, and thoughts. Yes, identities are dangerous and paradoxical things. They are expressions of inner selves, and a way the outside gets in. The United Fruit Company was born over a bottle of rum. In 1870, Lorenzo Dow Baker, skipper of the Boston schooner Telegraph, pulled into Jamaica for a taste of the island’s famous distilled alcohol and a load of bamboo. While he was drinking, a local tradesman came by offering green bananas; Baker bought 160 bunches at twenty-five cents each. He resold them in New York for up to $3.25 a bunch, a deal so sweet he couldn’t resist doing it again. By 1885, eleven ships were flying under the banner of the new Boston Fruit Company, bringing to the United States ten million bunches of bananas a year. United Fruit was formed in 1899, with assets that included more than 210,000 acres of land across the Caribbean and Central America and enough political clout that Honduras, Costa Rica, and other countries in the region became known as “banana republics.”

The United Fruit Company was born over a bottle of rum. In 1870, Lorenzo Dow Baker, skipper of the Boston schooner Telegraph, pulled into Jamaica for a taste of the island’s famous distilled alcohol and a load of bamboo. While he was drinking, a local tradesman came by offering green bananas; Baker bought 160 bunches at twenty-five cents each. He resold them in New York for up to $3.25 a bunch, a deal so sweet he couldn’t resist doing it again. By 1885, eleven ships were flying under the banner of the new Boston Fruit Company, bringing to the United States ten million bunches of bananas a year. United Fruit was formed in 1899, with assets that included more than 210,000 acres of land across the Caribbean and Central America and enough political clout that Honduras, Costa Rica, and other countries in the region became known as “banana republics.” This year, Tate is hosting four exhibitions devoted to women artists: Paula Rego, Lubaina Himid, Yayoi Kusama and Sophie Taeuber-Arp (a further show devoted to Magdalena Abakanowicz is in the pipeline). Opening on 15 July at Tate Modern, the exhibition ‘Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Living Abstraction’ comes with an excellent catalogue, which includes sixteen essays that survey her remarkable range. This Swiss artist, born in Davos in 1889, created textiles, beadwork bags and necklaces, cross-stitch embroidery, carnivalesque outfits for costume balls and a family of haunting marionettes, as well as designing furniture and interiors. She was also a Laban-trained dancer, a sculptor, an illustrator, co-editor of the important journal Plastique, a brilliant photographer and a significant abstract artist. And as if that were not enough, she gave continuous support to her husband, Jean Arp, and designed the modern vernacular house at Clamart in the southwestern suburbs of Paris where she and Arp lived from 1928 until being driven south by the German invasion in 1940. Her husband, whom she married in 1922, is regularly name-checked in surveys of 20th-century art, from Herbert Read’s A Concise History of Modern Painting to Norbert Lynton’s The Story of Modern Art. By contrast, Taeuber-Arp’s reputation was only properly recuperated in 2005 in Hal Foster, Rosalind Krauss, Yve-Alain Bois and Benjamin Buchloh’s generous Art Since 1900: Modernism, Antimodernism, Postmodernism.

This year, Tate is hosting four exhibitions devoted to women artists: Paula Rego, Lubaina Himid, Yayoi Kusama and Sophie Taeuber-Arp (a further show devoted to Magdalena Abakanowicz is in the pipeline). Opening on 15 July at Tate Modern, the exhibition ‘Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Living Abstraction’ comes with an excellent catalogue, which includes sixteen essays that survey her remarkable range. This Swiss artist, born in Davos in 1889, created textiles, beadwork bags and necklaces, cross-stitch embroidery, carnivalesque outfits for costume balls and a family of haunting marionettes, as well as designing furniture and interiors. She was also a Laban-trained dancer, a sculptor, an illustrator, co-editor of the important journal Plastique, a brilliant photographer and a significant abstract artist. And as if that were not enough, she gave continuous support to her husband, Jean Arp, and designed the modern vernacular house at Clamart in the southwestern suburbs of Paris where she and Arp lived from 1928 until being driven south by the German invasion in 1940. Her husband, whom she married in 1922, is regularly name-checked in surveys of 20th-century art, from Herbert Read’s A Concise History of Modern Painting to Norbert Lynton’s The Story of Modern Art. By contrast, Taeuber-Arp’s reputation was only properly recuperated in 2005 in Hal Foster, Rosalind Krauss, Yve-Alain Bois and Benjamin Buchloh’s generous Art Since 1900: Modernism, Antimodernism, Postmodernism. Television suits

Television suits  US President Joe Biden’s administration wants to create a US$6.5-billion agency to accelerate innovations in health and medicine — and revealed new details about the unit last month

US President Joe Biden’s administration wants to create a US$6.5-billion agency to accelerate innovations in health and medicine — and revealed new details about the unit last month

Cancer has occupied my intellectual and professional life for half a century now. Despite all the heartfelt investments in trying to find better solutions, I am still treating acute myeloid leukemia patients with the same two drugs I was using in 1977. It is a devastating, demoralizing reality I must live with on a daily basis as my entire clinical practice consists of leukemia patients or leukemia’s precursor state, pre-leukemia. My colleagues, treating other and more common cancers, are no better off. I obsess over what I have done wrong and what the field is doing wrong collectively.

Cancer has occupied my intellectual and professional life for half a century now. Despite all the heartfelt investments in trying to find better solutions, I am still treating acute myeloid leukemia patients with the same two drugs I was using in 1977. It is a devastating, demoralizing reality I must live with on a daily basis as my entire clinical practice consists of leukemia patients or leukemia’s precursor state, pre-leukemia. My colleagues, treating other and more common cancers, are no better off. I obsess over what I have done wrong and what the field is doing wrong collectively.