Safina Nabi in The Christian Science Monitor:

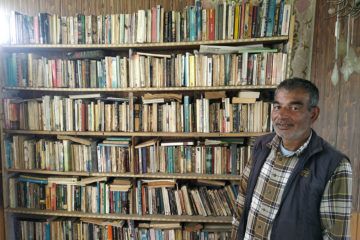

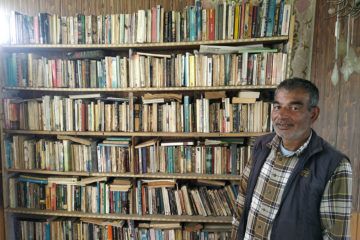

After climbing a stiff wooden stair, we reach the “Traveler’s Library,” its walls painted white and windows open on three sides. The front overlooks Dal Lake’s houseboats and other boats for everyday use. Next to an old green sofa is a woven wicker table. And on the right are Mr. Oata’s books. With about 600 volumes, this library may not look like much. But for years, this room has been a place where Kashmir – a beautiful but long fought-over Muslim-majority region, tucked at the top of India – has touched the wider world. It’s been an oasis for visitors, and readers; but most of all, for one book-lover who can’t read. “Ask as many questions as you can to get the information you require,” Mrs. Oata says, before her husband comes in. “He will not explain things on his own.” She laughs and leaves the room.

After climbing a stiff wooden stair, we reach the “Traveler’s Library,” its walls painted white and windows open on three sides. The front overlooks Dal Lake’s houseboats and other boats for everyday use. Next to an old green sofa is a woven wicker table. And on the right are Mr. Oata’s books. With about 600 volumes, this library may not look like much. But for years, this room has been a place where Kashmir – a beautiful but long fought-over Muslim-majority region, tucked at the top of India – has touched the wider world. It’s been an oasis for visitors, and readers; but most of all, for one book-lover who can’t read. “Ask as many questions as you can to get the information you require,” Mrs. Oata says, before her husband comes in. “He will not explain things on his own.” She laughs and leaves the room.

As Mr. Oata, dressed in a warm shirt and vest, walks me through his library I scan the names on the shelves. “Only Time Will Tell” and “The Sins of the Father,” by English novelist Jeffrey Archer. Next to them is Paulo Coelho, from Brazil. There are books by Jane Austen, Dan Brown, and Majgull Axelsson, a Swedish journalist. He speaks hesitantly, in a soft voice. But once he starts chatting about books, his voice overflows with enthusiasm.

Born in Kashmir, the eldest son of a plumber and a housewife, he left home at 16 in search of work to support his family. He moved across India, from one tourist destination to the next, selling Kashmiri arts and crafts. He still regrets not completing his formal education. Now and then, he noticed tourists at his stall holding books. One day, a man handed one to Mr. Oata, who asked him to summarize its contents. From then on, he asked book browsers if they’d be willing to swap, and tell him what the story was about – “and they would do it happily.” Over the years, he moved to India’s southeast, then west to Karnataka, selling jewelry, shawls, rugs, and hand-embroidered bags. Over time, he collected hundreds of books, mostly by international authors, and created his first small library. But he yearned to come back to the Kashmir Valley. So after much deliberation, he packed his books and went home in 2007. “I feel writers are always alive forever through their books, even after death, and for me that is such an interesting aspect,” Mr. Oata says, adding that his books are his “most precious possession.” “Though I cannot read, I can remember most of the books: their theme, the name of the author, and the country that the author belonged to,” he says. “I have remembered it all by remembering the color of the book, its cover page, and symbols.”

More here.

Today, many people see democracy as under threat in a way that only a decade ago seemed unimaginable. Following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, it seemed like democracy was the way of the future. But nowadays, the state of democracy looks very different; we hear about ‘backsliding’ and ‘decay’ and other descriptions of a sort of creeping authoritarianism. Some long-established democracies, such as the United States, are witnessing a violation of governmental norms once thought secure, and this has culminated in the recent insurrection at the US Capitol. If democracy is a torch that shines for a time before then burning out – think of Classical Athens and Renaissance city republics – it all feels as if we might be heading toward a new period of darkness. What can we do to reverse this apparent trend and support democracy?

Today, many people see democracy as under threat in a way that only a decade ago seemed unimaginable. Following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, it seemed like democracy was the way of the future. But nowadays, the state of democracy looks very different; we hear about ‘backsliding’ and ‘decay’ and other descriptions of a sort of creeping authoritarianism. Some long-established democracies, such as the United States, are witnessing a violation of governmental norms once thought secure, and this has culminated in the recent insurrection at the US Capitol. If democracy is a torch that shines for a time before then burning out – think of Classical Athens and Renaissance city republics – it all feels as if we might be heading toward a new period of darkness. What can we do to reverse this apparent trend and support democracy?

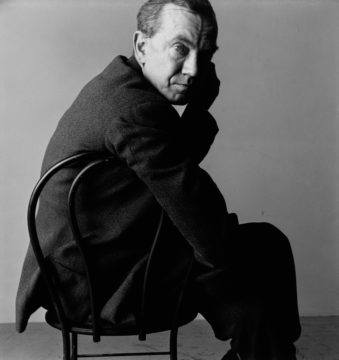

“The first thing I remember is sitting in a pram at the top of a hill with a dead dog lying at my feet.” So opens an early chapter of a memoir by Graham Greene, who is viewed by some—including Richard Greene (no relation), the author of a new biography of Graham, “

“The first thing I remember is sitting in a pram at the top of a hill with a dead dog lying at my feet.” So opens an early chapter of a memoir by Graham Greene, who is viewed by some—including Richard Greene (no relation), the author of a new biography of Graham, “ When researching my bio-fictional novel about Emily Dickinson, I read the erotic letters between Emily’s brother, Austin, and his mistress, Mabel Loomis Todd. The letters were direct, steamy, and quite mad in parts—for their paranoia and plotting—and I thought uncomfortably, No one on earth should be privy to these kinds of intimacies! When I first read Joyce’s letters to Nora, I was similarly gobsmacked. I recognized the frank language and the explicit, obscene imaginings. I liked, too, the intimate, tender spillover into poetic trances. But I was made wide-eyed, particularly, by his obsession with defecation as an erotic act. There are numerous references to Joyce’s love for what he calls “the most shameful and filthy act of the body.” Over and over he refers to being turned on by “shit,” “farts,” and “brown stains.” Even now, more familiar with the letters, I squirm a bit when I read this from Joyce to Nora: “The smallest things give me a great cockstand—a whorish movement of your mouth, a little brown stain on the seat of your white drawers, a sudden dirty word spluttered out by your wet lips, a sudden immodest noise made by you behind and then a bad smell slowly curling up out of your backside. At such moments I feel mad to do it in some filthy way, to feel your hot lecherous lips sucking away at me.” This was an utterly private sharing between lovers, the things they traded to bind themselves together, and Joyce’s fetish ought not bother me at all, as I shouldn’t know about it. Although, anyone who has read Molly Bloom’s wondrous speech in the Penelope episode of Ulysses might reasonably guess at Joyce’s delight in the coprophilic. When Molly wants money, she plans to let Bloom kiss her bottom, saying he can “stick his tongue 7 miles up my hole as hes there my brown part then Ill tell him I want £1.”

When researching my bio-fictional novel about Emily Dickinson, I read the erotic letters between Emily’s brother, Austin, and his mistress, Mabel Loomis Todd. The letters were direct, steamy, and quite mad in parts—for their paranoia and plotting—and I thought uncomfortably, No one on earth should be privy to these kinds of intimacies! When I first read Joyce’s letters to Nora, I was similarly gobsmacked. I recognized the frank language and the explicit, obscene imaginings. I liked, too, the intimate, tender spillover into poetic trances. But I was made wide-eyed, particularly, by his obsession with defecation as an erotic act. There are numerous references to Joyce’s love for what he calls “the most shameful and filthy act of the body.” Over and over he refers to being turned on by “shit,” “farts,” and “brown stains.” Even now, more familiar with the letters, I squirm a bit when I read this from Joyce to Nora: “The smallest things give me a great cockstand—a whorish movement of your mouth, a little brown stain on the seat of your white drawers, a sudden dirty word spluttered out by your wet lips, a sudden immodest noise made by you behind and then a bad smell slowly curling up out of your backside. At such moments I feel mad to do it in some filthy way, to feel your hot lecherous lips sucking away at me.” This was an utterly private sharing between lovers, the things they traded to bind themselves together, and Joyce’s fetish ought not bother me at all, as I shouldn’t know about it. Although, anyone who has read Molly Bloom’s wondrous speech in the Penelope episode of Ulysses might reasonably guess at Joyce’s delight in the coprophilic. When Molly wants money, she plans to let Bloom kiss her bottom, saying he can “stick his tongue 7 miles up my hole as hes there my brown part then Ill tell him I want £1.” After climbing a stiff wooden stair, we reach the “Traveler’s Library,” its walls painted white and windows open on three sides. The front overlooks Dal Lake’s houseboats and other boats for everyday use. Next to an old green sofa is a woven wicker table. And on the right are Mr. Oata’s books. With about 600 volumes, this library may not look like much. But for years, this room has been a place where Kashmir – a beautiful but long fought-over Muslim-majority region, tucked at the top of India – has touched the wider world. It’s been an oasis for visitors, and readers; but most of all, for one book-lover who can’t read. “Ask as many questions as you can to get the information you require,” Mrs. Oata says, before her husband comes in. “He will not explain things on his own.” She laughs and leaves the room.

After climbing a stiff wooden stair, we reach the “Traveler’s Library,” its walls painted white and windows open on three sides. The front overlooks Dal Lake’s houseboats and other boats for everyday use. Next to an old green sofa is a woven wicker table. And on the right are Mr. Oata’s books. With about 600 volumes, this library may not look like much. But for years, this room has been a place where Kashmir – a beautiful but long fought-over Muslim-majority region, tucked at the top of India – has touched the wider world. It’s been an oasis for visitors, and readers; but most of all, for one book-lover who can’t read. “Ask as many questions as you can to get the information you require,” Mrs. Oata says, before her husband comes in. “He will not explain things on his own.” She laughs and leaves the room. Some studies estimate that a large proportion of the population in Europe and the United States — as high as 50% — experiences chronic pain

Some studies estimate that a large proportion of the population in Europe and the United States — as high as 50% — experiences chronic pain Philosophy of science, in its early days, dedicated itself to justifying the ways of Science to Man. One might think this was a strange task to set for itself, for it is not as if in the early and middle 20th century there was widespread doubt about the validity of science. True, science had become deeply weird, with Einstein’s relativity and quantum mechanics. And true, there was irrationalism aplenty, culminating in two world wars and the invention of TV dinners. But societies around the world generally did not hold science in ill repute. If anything, technologically advanced cultures celebrated better imaginary futures through the steady march of scientific progress.

Philosophy of science, in its early days, dedicated itself to justifying the ways of Science to Man. One might think this was a strange task to set for itself, for it is not as if in the early and middle 20th century there was widespread doubt about the validity of science. True, science had become deeply weird, with Einstein’s relativity and quantum mechanics. And true, there was irrationalism aplenty, culminating in two world wars and the invention of TV dinners. But societies around the world generally did not hold science in ill repute. If anything, technologically advanced cultures celebrated better imaginary futures through the steady march of scientific progress.

For some time, Sir Kazuo Ishiguro has been slyly replacing Dame Iris Murdoch as the author to whom I most regularly return. His enchanting and disturbing new novel, Klara and the Sun, his first since winning the 2017 Nobel Prize, is unlikely to diminish this trend. I wrote in a

For some time, Sir Kazuo Ishiguro has been slyly replacing Dame Iris Murdoch as the author to whom I most regularly return. His enchanting and disturbing new novel, Klara and the Sun, his first since winning the 2017 Nobel Prize, is unlikely to diminish this trend. I wrote in a  have instrumental value. That is, the value of given technology lies in the various ways in which we can use it, no more, and no less. For example, the value of a hammer lies in our ability to make use of it to hit nails into things. Cars are valuable insofar as we can use them to get from A to B with the bare minimum of physical exertion. This way of viewing technology has immense intuitive appeal, but I think it is ultimately unconvincing. More specifically, I want to argue that technological artifacts are capable of embodying value. Some argue that this value is to be accounted for in terms of the

have instrumental value. That is, the value of given technology lies in the various ways in which we can use it, no more, and no less. For example, the value of a hammer lies in our ability to make use of it to hit nails into things. Cars are valuable insofar as we can use them to get from A to B with the bare minimum of physical exertion. This way of viewing technology has immense intuitive appeal, but I think it is ultimately unconvincing. More specifically, I want to argue that technological artifacts are capable of embodying value. Some argue that this value is to be accounted for in terms of the