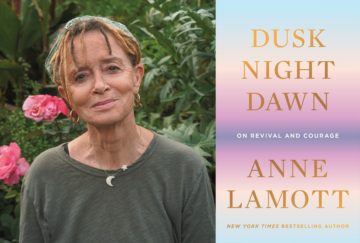

Mary Elizabeth William in Salon:

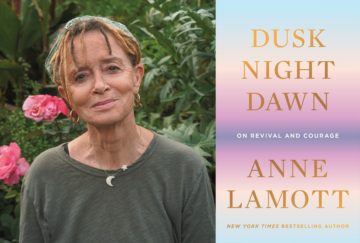

“That’s really all I write about, is hope and despair,” says Anne Lamott. Clearly, she was born into the era she was meant for. The bestselling author of durable classics like “Bird by Bird” and “Operating Instructions” is back once more with a new book, a new(ish) marriage and very much the same curiosity, humanity and sense of humor that been her brand for nearly 30 years. “Dusk, Night, Dawn: On Revival and Courage” considers friendship, forgiveness, aging and the collective “existential exhaustion” that haunts us. Salon spoke to Lamott recently about what’s changed since she wrote prophetically about “stockpiling for the apocalypse,” and finding grace in a big box store run.

“That’s really all I write about, is hope and despair,” says Anne Lamott. Clearly, she was born into the era she was meant for. The bestselling author of durable classics like “Bird by Bird” and “Operating Instructions” is back once more with a new book, a new(ish) marriage and very much the same curiosity, humanity and sense of humor that been her brand for nearly 30 years. “Dusk, Night, Dawn: On Revival and Courage” considers friendship, forgiveness, aging and the collective “existential exhaustion” that haunts us. Salon spoke to Lamott recently about what’s changed since she wrote prophetically about “stockpiling for the apocalypse,” and finding grace in a big box store run.

…Now it is coming out into the world when we are one year into this very strange and deeply sad time. How do you approach this book in particular now?

…I’ve just been enraged since February of 2020, when the first cases surfaced and it was clearly not going to be addressed, even recognized, like the U.S. recognizes nations. We weren’t going to recognize it as a reality and there was going to be no real help. There was only going to be propaganda. I’ve been so angry for so long. But I’ll tell you I’m less angry this year. I am a lot less angry.

What’s that great line of Martin Luther King’s? Don’t let them get you to hate them. Even though I did hate them and kept going into that rabbit hole all through 2020, I kept remembering that line, and how it really destroys your center of gravity. It destroys yourself. I do have an inner Donald Trump, this petty, narcissistic blowhard, but to hate him took away my mostly “me” self, which is really decent and loving and caring, and mostly compassionate and mostly tenderhearted.

When I go into the hate, it’s like this cold sheet metal heart that I operate from and then I’m of no good to anyone. Probably every book I’ve written has had a great sorrow in it. My dad, and then my friend Pammy in “Operating Instructions,” I’ve just been a person who’s had a lot of death in her life and also I’m a person who doesn’t run from people when they are experiencing death. My best friend’s child just died. He was 23. She’s who said she had to keep changing the goalposts on “okay.” All of the books have been about that mixed grill, and that it’s devastating to be here on earth and to have had children and to not be able to save them from really much of anything.

More here.

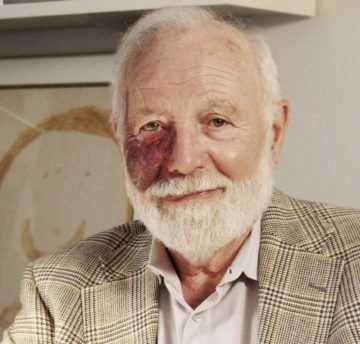

The mathematics community lost a titan with the passing last month of Isadore “Is” Singer. Born in Detroit in 1924, Is was a visionary, transcending divisions between fields of mathematics as well as those between mathematics and quantum physics. He pursued deep questions and inspired others in his original research, wide-ranging lectures, mentoring of young researchers and advocacy in the public sphere.

The mathematics community lost a titan with the passing last month of Isadore “Is” Singer. Born in Detroit in 1924, Is was a visionary, transcending divisions between fields of mathematics as well as those between mathematics and quantum physics. He pursued deep questions and inspired others in his original research, wide-ranging lectures, mentoring of young researchers and advocacy in the public sphere.

A distinguishing mark of classical political philosophy is its focus on the ruling claims of regimes. Classical philosophers sifted and evaluated the distinctive qualities invoked to legitimate governance by some number of

A distinguishing mark of classical political philosophy is its focus on the ruling claims of regimes. Classical philosophers sifted and evaluated the distinctive qualities invoked to legitimate governance by some number of  Shortly after 335 B.C., within a newly built library tucked just east of Athens’ limestone city walls, a free-thinking Greek polymath by the name of Aristotle gathered up an armful of old theater scripts. As he pored over their delicate papyrus in the amber flicker of a sesame lamp, he was struck by a revolutionary idea: What if literature was an invention for making us happier and healthier? The idea made intuitive sense; when people felt bored, or unhappy, or at a loss for meaning, they frequently turned to plays or poetry. And afterwards, they often reported feeling better. But what could be the secret to literature’s feel-better power? What hidden nuts-and-bolts conveyed its psychological benefits?

Shortly after 335 B.C., within a newly built library tucked just east of Athens’ limestone city walls, a free-thinking Greek polymath by the name of Aristotle gathered up an armful of old theater scripts. As he pored over their delicate papyrus in the amber flicker of a sesame lamp, he was struck by a revolutionary idea: What if literature was an invention for making us happier and healthier? The idea made intuitive sense; when people felt bored, or unhappy, or at a loss for meaning, they frequently turned to plays or poetry. And afterwards, they often reported feeling better. But what could be the secret to literature’s feel-better power? What hidden nuts-and-bolts conveyed its psychological benefits? “That’s really all I write about, is hope and despair,” says Anne Lamott. Clearly, she was born into the era she was meant for. The bestselling author of durable classics like “Bird by Bird” and “Operating Instructions” is back once more with a new book, a new(ish) marriage and very much the same curiosity, humanity and sense of humor that been her brand for nearly 30 years.

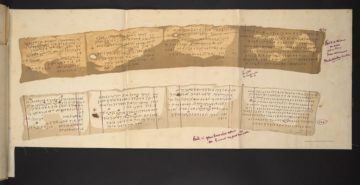

“That’s really all I write about, is hope and despair,” says Anne Lamott. Clearly, she was born into the era she was meant for. The bestselling author of durable classics like “Bird by Bird” and “Operating Instructions” is back once more with a new book, a new(ish) marriage and very much the same curiosity, humanity and sense of humor that been her brand for nearly 30 years.  In 1883, a Jerusalem antiquities dealer named Moses Wilhelm Shapira announced the discovery of a remarkable artifact: 15 manuscript fragments, supposedly discovered in a cave near the Dead Sea. Blackened with a pitchlike substance, their paleo-Hebrew script nearly illegible, they contained what Shapira claimed was the “original” Book of Deuteronomy, perhaps even Moses’ own copy.

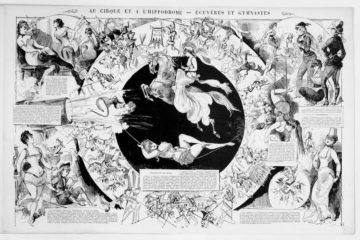

In 1883, a Jerusalem antiquities dealer named Moses Wilhelm Shapira announced the discovery of a remarkable artifact: 15 manuscript fragments, supposedly discovered in a cave near the Dead Sea. Blackened with a pitchlike substance, their paleo-Hebrew script nearly illegible, they contained what Shapira claimed was the “original” Book of Deuteronomy, perhaps even Moses’ own copy. There is a dual quality to Émilie’s life at this time: her bravado in the ring and her celebrity are ranged against repeated accounts of a modest, single-minded loner. After her mother’s death in 1880 and Clotilde’s retirement from the circus, she traveled only with a maid and a huge, white shaggy dog called Turc who followed her everywhere and slept at the foot of her bed. She would live alone in a small apartment near the circus at which she was engaged, and was said to enjoy books, music, and art, and receive few guests. She would only permit admirers to give her flowers—she had no interest in jewelry or more lucrative tokens. When her followers crammed into the circus stables to see her, she offered them only “banal” smiles calculated to be polite but not enticing. Not that that mattered. The circus managers issued invitations to every aristocrat in town as soon as her first performance was scheduled, feeding on Clotilde’s notoriety. Some of the writing about her is feverish: “Our little queen!” “The most beautiful will-o-the-wisp anyone could imagine!” “A female centaur!” “The diva of equitation, the Patti of haute école, the most intrepid amazone, the most charming, the most dizzying experience since the advent of the Amazons!”

There is a dual quality to Émilie’s life at this time: her bravado in the ring and her celebrity are ranged against repeated accounts of a modest, single-minded loner. After her mother’s death in 1880 and Clotilde’s retirement from the circus, she traveled only with a maid and a huge, white shaggy dog called Turc who followed her everywhere and slept at the foot of her bed. She would live alone in a small apartment near the circus at which she was engaged, and was said to enjoy books, music, and art, and receive few guests. She would only permit admirers to give her flowers—she had no interest in jewelry or more lucrative tokens. When her followers crammed into the circus stables to see her, she offered them only “banal” smiles calculated to be polite but not enticing. Not that that mattered. The circus managers issued invitations to every aristocrat in town as soon as her first performance was scheduled, feeding on Clotilde’s notoriety. Some of the writing about her is feverish: “Our little queen!” “The most beautiful will-o-the-wisp anyone could imagine!” “A female centaur!” “The diva of equitation, the Patti of haute école, the most intrepid amazone, the most charming, the most dizzying experience since the advent of the Amazons!” In 1768, the German philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder paid a visit to the French city of Nantes. “I am getting to know the French language and ways of thinking,” he wrote to fellow-philosopher Johann Georg Hamann. But, “the closer my acquaintance with them is, the greater my sense of alienation becomes”.

In 1768, the German philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder paid a visit to the French city of Nantes. “I am getting to know the French language and ways of thinking,” he wrote to fellow-philosopher Johann Georg Hamann. But, “the closer my acquaintance with them is, the greater my sense of alienation becomes”. …although I’ve written tens of thousands

…although I’ve written tens of thousands  I entered Martin Gurri’s world on August 1, 2015. Though I hadn’t read

I entered Martin Gurri’s world on August 1, 2015. Though I hadn’t read  “Kan kun være malet af en gal Mand!” (“Can only have been painted by a madman!”) appears on Norwegian artist Edvard Munch’s most famous painting The Scream.

“Kan kun være malet af en gal Mand!” (“Can only have been painted by a madman!”) appears on Norwegian artist Edvard Munch’s most famous painting The Scream.  One of the oldest imperatives of American electoral politics is to define your opponents before they can define themselves. So it was not surprising when, in the summer of 1963, Nelson Rockefeller, a centrist Republican governor from New York, launched a preëmptive attack against Barry Goldwater, a right-wing Arizona senator, as both men were preparing to run for the Presidential nomination of the Republican Party. But the nature of Rockefeller’s attack was noteworthy. If the G.O.P. embraced Goldwater, an opponent of civil-rights legislation, Rockefeller suggested that it would be pursuing a “program based on racism and sectionalism.” Such a turn toward the elements that Rockefeller saw as “fantastically short-sighted” would be potentially destructive to a party that had held the White House for eight years, owing to the popularity of Dwight Eisenhower, but had been languishing in the minority in Congress for the better part of three decades. Some moderates in the Republican Party thought that Rockefeller was overstating the threat, but he was hardly alone in his concern. Richard Nixon, the former Vice-President, who had received substantial Black support in his 1960 Presidential bid, against John F. Kennedy, told a reporter for Ebony that “if Goldwater wins his fight, our party would eventually become the first major all-white political party.” The Chicago Defender, the premier Black newspaper of the era, concurred, stating bluntly that the G.O.P. was en route to becoming a “white man’s party.”

One of the oldest imperatives of American electoral politics is to define your opponents before they can define themselves. So it was not surprising when, in the summer of 1963, Nelson Rockefeller, a centrist Republican governor from New York, launched a preëmptive attack against Barry Goldwater, a right-wing Arizona senator, as both men were preparing to run for the Presidential nomination of the Republican Party. But the nature of Rockefeller’s attack was noteworthy. If the G.O.P. embraced Goldwater, an opponent of civil-rights legislation, Rockefeller suggested that it would be pursuing a “program based on racism and sectionalism.” Such a turn toward the elements that Rockefeller saw as “fantastically short-sighted” would be potentially destructive to a party that had held the White House for eight years, owing to the popularity of Dwight Eisenhower, but had been languishing in the minority in Congress for the better part of three decades. Some moderates in the Republican Party thought that Rockefeller was overstating the threat, but he was hardly alone in his concern. Richard Nixon, the former Vice-President, who had received substantial Black support in his 1960 Presidential bid, against John F. Kennedy, told a reporter for Ebony that “if Goldwater wins his fight, our party would eventually become the first major all-white political party.” The Chicago Defender, the premier Black newspaper of the era, concurred, stating bluntly that the G.O.P. was en route to becoming a “white man’s party.” The singer and guitarist Julien Baker makes raw, ghostly rock music that’s rooted in personal confession. But, unlike some artists operating in that mode, she’s figured out how to turn fragility into a display of fortitude. Baker’s songs—which explore themes of self-sabotage, atonement, and restitution—are aching but tough. This stems, in part, from Baker’s spiritual upbringing. She was raised in a devout Christian family near Memphis, Tennessee, and sang in church. When she came out as gay, at seventeen, she prepared herself for a swift denunciation, but her parents were compassionate. (Her father began scouring the Bible for passages about acceptance.) It’s possible to hear the echoes of Christian hymnals in her first two albums—ideas of love and grace, mentions of God and rejoicing. Baker has a tattoo that reads “God exists” and has said that she senses a kind of divine presence in art, or, as she once put it, evidence of “the possibility of man to be good.”

The singer and guitarist Julien Baker makes raw, ghostly rock music that’s rooted in personal confession. But, unlike some artists operating in that mode, she’s figured out how to turn fragility into a display of fortitude. Baker’s songs—which explore themes of self-sabotage, atonement, and restitution—are aching but tough. This stems, in part, from Baker’s spiritual upbringing. She was raised in a devout Christian family near Memphis, Tennessee, and sang in church. When she came out as gay, at seventeen, she prepared herself for a swift denunciation, but her parents were compassionate. (Her father began scouring the Bible for passages about acceptance.) It’s possible to hear the echoes of Christian hymnals in her first two albums—ideas of love and grace, mentions of God and rejoicing. Baker has a tattoo that reads “God exists” and has said that she senses a kind of divine presence in art, or, as she once put it, evidence of “the possibility of man to be good.” There is a story about René Descartes according to which the philosopher once owned a female automaton so convincing that a superstitious mariner, seeing the machine in operation, declared it the work of the devil and threw it into the sea. In some versions, Descartes is said to have built the automaton to replace his illegitimate daughter, Francine, who died in childhood. Though apocryphal, the tale persists because it combines a moving human tragedy with an intellectual problem – the relationship between mind and matter – that was central to Descartes’s own philosophy. It is a thought experiment disguised as a fairy tale, or perhaps vice versa.

There is a story about René Descartes according to which the philosopher once owned a female automaton so convincing that a superstitious mariner, seeing the machine in operation, declared it the work of the devil and threw it into the sea. In some versions, Descartes is said to have built the automaton to replace his illegitimate daughter, Francine, who died in childhood. Though apocryphal, the tale persists because it combines a moving human tragedy with an intellectual problem – the relationship between mind and matter – that was central to Descartes’s own philosophy. It is a thought experiment disguised as a fairy tale, or perhaps vice versa. I stumbled upon the legend of Nanda Devi and Nanda Kot and the lost CIA plutonium on a cold October night in 1987, sitting with friends, swilling cheap malt liquor around a roaring campfire in Yosemite. To my best recollection, Tucker recounted the most outrageous climbing yarn I’d ever heard. Tucker, whose low-slung build lent him an authoritative air, was one of those whose expression becomes more earnest and animated with each drink.

I stumbled upon the legend of Nanda Devi and Nanda Kot and the lost CIA plutonium on a cold October night in 1987, sitting with friends, swilling cheap malt liquor around a roaring campfire in Yosemite. To my best recollection, Tucker recounted the most outrageous climbing yarn I’d ever heard. Tucker, whose low-slung build lent him an authoritative air, was one of those whose expression becomes more earnest and animated with each drink.